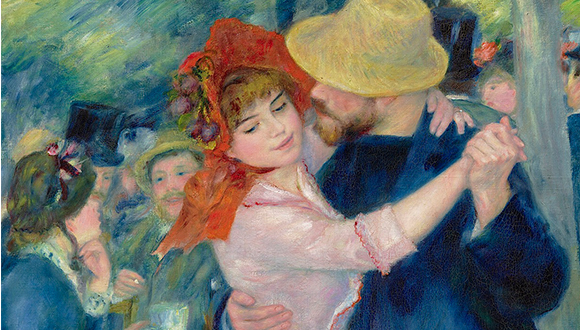

Renoir, “Dance at Bougival” (detail of life-sized painting), 1883. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

This photo-essay treats two exhibitions at Houston’s MFA: Calder-Picasso, and Incomparable Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The former is an exhibition of 80 objects curated by the grandsons of Alexander Calder (1898–1976) and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). The latter consists of 106 paintings and works on paper organized for the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. After a nationwide COVID shutdown of Australia, the exhibition was re-routed to Houston.

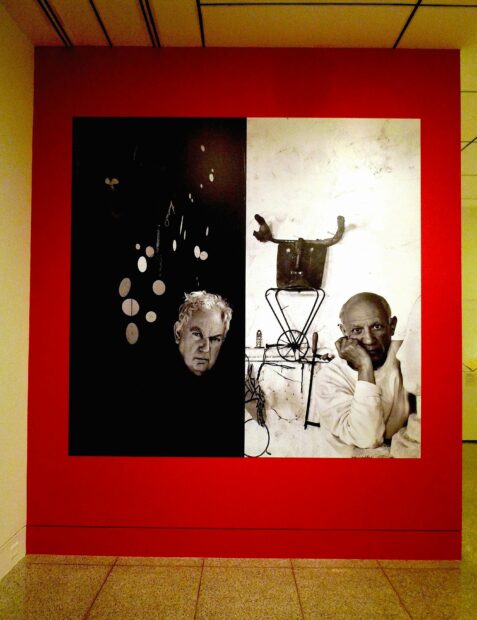

Entrance to the “Calder-Picasso” exhibition, with photos of Calder and Picasso. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Alexander S. C. Rower (b. 1963), the grandson of Alexander Calder, is the founder and president of the Calder Foundation. He initiated the foundation to catalogue, document, and study Calder’s work. His co-curator Bernard Ruiz-Picasso (b. 1959) is the grandson of Pablo Picasso and the son of Paul and Christine Ruiz-Picasso. With his mother he co-founded the Museo Picasso Málaga, and with his wife Almine he co-founded the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte. Both Rower and Ruiz-Picasso have curated and collaborated on numerous exhibitions featuring the work of their respective grandfathers.

Picasso and Calder only met four times. The first meeting took place in April 1931, when Picasso visited a Calder exhibition at the Galerie Percier in Paris. Their most significant interaction took place in July of 1937 at the Exposition Internationale in Paris.

Hugo Paul Herdeg, Portrait of Alexander Calder in the Spanish Pavilion, July, 1937, with Calder’s “Mercury Fountain” (now in the Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona) in the foreground and Picasso’s “Guernica” (now in the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid) in the background.

Picasso exhibited Guernica in the Spanish Pavilion. This now world-famous anti-war mural was a response to the bombing of a Basque village by Nazi and Italian planes. Calder’s Mercury Fountain — which also referenced the Spanish Civil War — was installed in the center of the pavilion. It referred to the protracted siege of the Spanish town of Almadén — the site of an ancient and productive mercury mine — by fascist forces under General Franco. The Spanish Republic needed revenue from the mine for the war effort.

Picasso’s and Calder’s common political sympathies and interactions in 1937 did not lead to a friendship between the two artists, though they met again in Antibes in 1952 and Vallauris in 1953.

Calder-Picasso does not assess questions of influence and priority. If it were to consider those issues, then the exhibition would have needed to include Picasso’s ground breaking early Cubist work. Instead, the exhibition begins in the late 1920s. A few of Picasso’s most schematic paintings (and many drawings) from 1910-1911 suggest wire-like configurations of human forms. How familiar was Calder with Picasso’s early Cubism, and did it influence his wire sculptures? Additionally, two roughly-hewn wood sculptures by Calder called Caryatid (1928) have their closest counterpart in Picasso’s oeuvre in primitivizing wood sculptures that he made in 1907 and 1908. I don’t know if these issues were addressed in the catalogue, because the museum declined to send me a review copy. In many instances, the exhibition did not feature the works by the two artists that resembled each other the most.

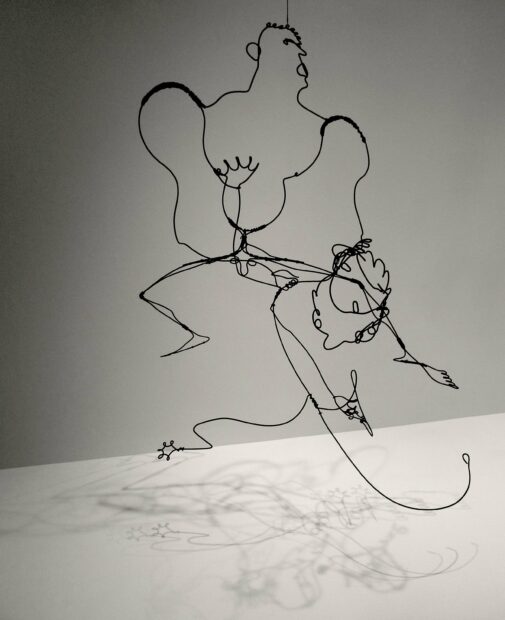

Calder-Picasso is spaciously installed, and, for the most part, Calder’s work is displayed most advantageously. The exhibition makes great use of Calder’s forms in space. The mobiles, in particular, energize the space with the shadows they create as they twist and turn (the base in the foreground of the installation shot illustrated above serves to “display” the equally mobile shadow of Calder’s sculpture). The stabiles, too, are amplified by the shadows they cast.

Picasso’s most important sculptures in the exhibition are rather small, such as the study for the monument to Apollinaire, which is under 15 inches tall.

In the above installation shot, Calder’s Untitled, a mobile from 1947, is beautifully displayed with a circular, shadow-displaying platform beneath it. It’s a pleasure to watch it turn. To its left, however, Picasso’s Bull’s Head (1942) is behind a barrier and hangs so high that it is difficult to appreciate it. The Picasso is a bronze version of his boldest and simplest assemblage, which the artist fashioned out of the seat and handlebars of a bicycle. When better displayed, it has had a very powerful presence in several sculpture exhibitions I have seen. But in Calder-Picasso it seems wasted.

Installation shot of “Calder-Picasso,” with paintings by Picasso and sculptures by Calder. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Picasso’s major painting Reclining Nude (1932) (illustrated above) has more impact and is placed near Calder’s Object with Red Disks (1931). I wonder why a better juxtaposition of similar physical or thematic characteristics was not made between the Picasso and the Calder.

Calder’s most astonishing wire mobile — and the one that most needs to be experienced in person — is Hercules and Lion. The epic battle between hero and lion comes to life as the intertwined wire figures (and the far more complex shadow figures) twist and grapple before our eyes.

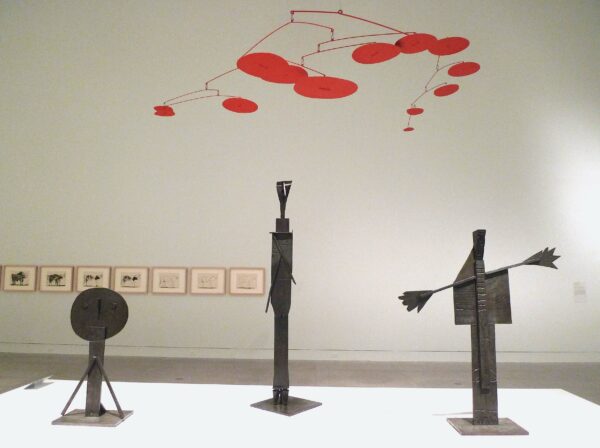

Installation shot of “Calder-Picasso,” with bronze versions of three “Bathers”(1956) by Picasso under a Calder mobile called “Red Lilly Pads” (1956). Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

A pair of water-themed works from the same year are installed in the center of a large gallery.

Installation shot of same gallery, with 11 states of Picasso’s “The Bull” (1945-1946) in the left foreground. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Picasso created a hulking bull in his second state of the above lithograph, which he gradually dematerialized until it was just a wire figure in its final state.

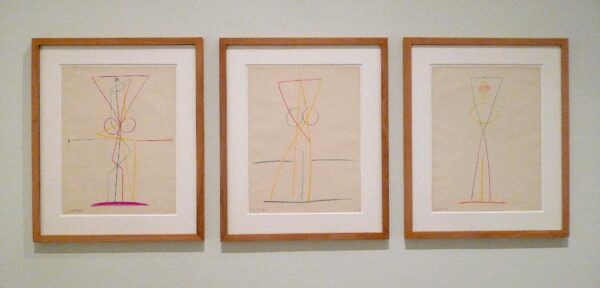

Pablo Picasso, Three versions of “Standing Nude,” 1946, colored pencils on wove drawing paper, Musée national Picasso-Paris. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

These three drawings by Picasso are fascinating examples of the artist’s simplifying geometry.

Installation shot of “Calder-Picasso,” with Calder’s “Dancer” (1944, bronze), Picasso’s “Vase with Flower” (1951, bronze), Calder’s “One One Knee” (1944, aluminum), and Calder’s “Tightrope Worker (Woman on Cord)” (1944, bronze, rod, and string). Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The three Calder statues in the above photograph were models for a public art project. They would have been 30-40-feet high, if the project had been realized. Picasso’s sculptures often look anthropomorphic. In this company, Vase with Flower looks particularly anthropomorphic.

Calder-Picasso has many interesting works by both artists. I had hoped, however, that it would be a more ambitious exhibition from an art historical perspective.

Calder-Picasso was organized in partnership with the Calder Foundation, New York; the Musée National Picasso Paris (MNPP); and the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte. It premiered at the MNPP in 2019, and traveled to the Museo Picasso Málaga, the De Young Museum in San Francisco, and the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Ann Dumas organized the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston presentation, based on a concept by Claire Garnier, Emilia Philippot, Alexander S. C. Rower and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso. The exhibition runs through January 30 at the MFAH.

****

Incomparable Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Founded in 1870, Boston’s MFA has one of the largest and finest collections of 19th century paintings in the world. Bostonians were early and avid collectors of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and their precursors. In 1903, the Boston museum became the first U.S. museum to acquire a Degas.

Incomparable Impressionism took years to plan. When the exhibition’s run in Australia was truncated by the COVID pandemic, the Houston MFA quickly raised $800,000 to secure the exhibition. It is situated in light-filled galleries on the second floor of the Beck Building.

Incomparable Impressionism begins with the Barbizon painters, who were precursors of the Impressionists. They include Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Charles Francois Daubigny (van Gogh’s depiction of the latter’s house and garden was treated in my previous Glasstire review. Read that here).

Incomparable Impressionism is arranged in nine thematic groupings: The Barbizon School; Boudin, Mentor To Monet; Watery Surfaces: Mastery And Innovation; Impressionist Still Life; Renoir: A Fantastic, Nervous Improvisator; Pissarro: Teacher And Student; Impressionists And The City; Impressionist Printmaking; and Monet: From Fontainebleau To Giverny.

It includes sections on particular artists, as well as groupings by genre. The exhibition’s greatest strength is groups of works by core members of the Impressionist circle. Incomparable Impressionism culminates in an impressive group of 15 paintings by Claude Monet, the quintessential Impressionist. The Impressionists habitually worked outside, painting directly from the motif in an attempt to render forms, colors (including colored shadows), and the fugitive effects caused by the play of light directly onto their canvases. Monet developed the practice of working on several canvases in a single day, moving from one canvas to another as the light changed. In the nineteenth century, there were many developments in optics and color theory, which were of great interest to the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, who made use of new scientific theories. But one should not conclude — as was often done in the twentieth century — that the Impressionists were somehow “objective,” disinterested in their subject matter, or that they did not paint for expressive purposes.

Painted over a span of three decades, the Monets in the exhibition range from the Fontainebleau Forest (where the Barbizon painters worked) to the artist’s late paintings of water lilies. Many of Monet’s favorite motifs are represented in the exhibition, and they provide a mini-survey of his development as an artist.

The most eclectic grouping is called Watery Surfaces. It includes two paintings by the Norwegian Frits Thaulow (one is in the center of the above photograph).

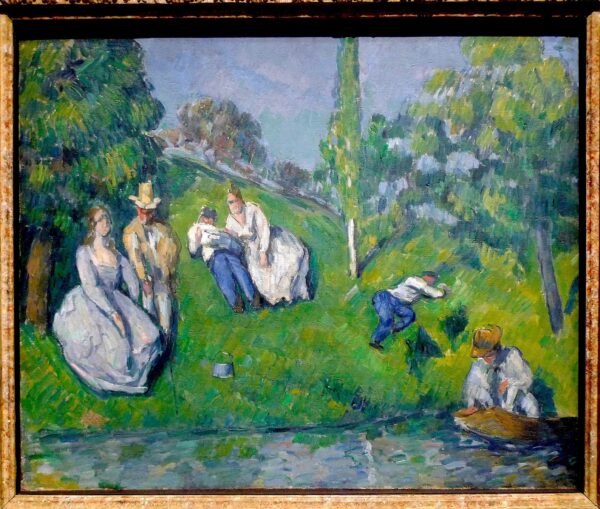

One of my favorites among these paintings is Cézanne’s early genre painting called The Pond, c. 1877-1879. This small, enigmatic painting features strange groupings of figures — though they are not as strange as many of his genre paintings.

Cézanne famously said of Monet: “He is just an eye, but my God, what an eye.” In The Pond he uses parallel strokes of paint that form clusters in an overall pattern. These pronounced accents run counter to the Impressionist concern to render the visible, to capture optical sensations. Cézanne, who is considered a Post-Impressionist, is already rendering an extremely subjective personal vision. Even in this early painting, space is compressed in a very subjective manner. There is little sense of time of day, nor of the details of a specific locale. The putative water in the foreground is not treated very differently from the grass.

The still life section ranges from the 1860s to the 1890s, with works by Edouard Manet, Gustave Courbet, Berthe Morisot, and Paul Cézanne. Henri Fantin-Latour’s work from the 1860s and 1870s is particularly well-represented (the second, fourth, and fifth paintings in the installation shot illustrated above are by him). The centerpiece in the installation shot is an early and complex flower painting by Renoir from around 1869.

This still life by Berthe Morisot is the only painting by a woman artist in the Incomparable Impressionism exhibition. Morisot studied with and was advised by a number of artists, though she found her own path. She exhibited at the official state-sanctioned Salon (1864-1868) and around 1867-1868, was introduced to Manet by Fantin-Latour. Though Manet encouraged her to stay within the Salon system, Morisot became a founding member of the Impressionists. She was an enthusiastic exhibitor in the Impressionist exhibitions, which began in 1874, and many artists and writers attended gatherings at her home.

Though Morisot often painted flowers, White Flowers in a Bowl is one of her rare still life paintings. While most of the Impressionists and the artists they admired revelled in the opportunity to paint multi-colored bouquets, Morisot has chosen white flowers. White, in fact, figures prominently in many of Morisot’s paintings of interiors. Beneath the bowl of flowers in particular, one can see the slashing brushstrokes, one of her hallmarks as a painter. Morisot also lets areas of bare canvas and thin underpainting show through.

Renoir’s Dance at Bougival is one of the Boston museum’s most popular paintings. It depicts a couple dancing in an outdoor café. Bougival, which is west of Paris on the river Seine, was popular with residents of the city. Renoir was one of several Impressionists who painted at Bougival. They made middle class recreation and sociability the subject of art, which hitherto placed a priority on historical and mythological scenes.

Dance at Bougival is one of three full-length dance paintings commissioned by the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Sketchy, Impressionist brushwork is most evident in the background, which also features casually posed and cropped figures. In particular, note the two black-top hats stacked behind the male dancer’s straw hat. Renoir has portrayed his two dancing figures with more conventional brushwork. Renoir increasingly chose to represent weighty, solid forms rather than those seemingly dissolved by bright sunlight and refractions that typified his Impressionist work.

Edgar Degas is well represented in this portion of the exhibition. All six works in the above installation shot are by him

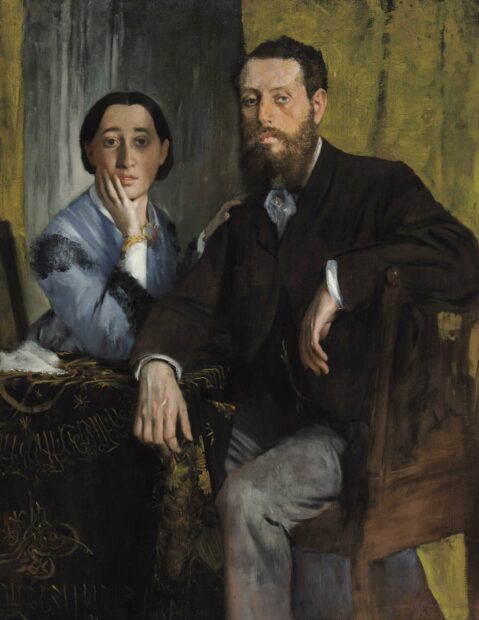

Edgar Degas, “Edmondo and Therese Morbilli,” c. 1865, oil on canvas. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Degas is a hard artist to categorize. Although he exhibited in most of the Impressionist exhibitions and he is virtually always grouped with them. The standard Impressionist practice was to paint out of doors in a spontaneous manner in order to capture transitory effects and bright colors. Degas, however, worked in the studio and had a disdain for spontaneity and working outside. Whereas the Impressionists virtually banished the color black, Degas often made extensive use of it in his paintings (though he used electric colors in his pastels). Like Manet and the Impressionists, Degas often depicted scenes of modern life. He also often utilized strange viewpoints, croppings, and poses. Degas, who revered the old masters, is regarded as the finest draftsman of his era. He was also deeply concerned with portraying the psychological states of the sitters he painted — which is not a quality generally associated with Impressionism.

Degas’s double portrait of his sister, Thérèse, and her husband, Edmondo Morbilli (pictured above), reveals the artist’s interest in conveying psychological states. One can also see the influence of the French Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in the pose and facial features of Thérèse. Degas worked in a very studious manner — often with many preparatory drawings — that was antithetical to Impressionist practice.

Manet is also also hard to categorize. He and Courbet are recognized as the founders of modern art in France. Manet was the quintessential painter of modern life. He also introduced the alla prima technique (painting directly on the canvas without a colored primer and multiple layers of paint and glazes) that was fundamental to Impressionism. Manet both influenced and was influenced by the Impressionists, yet he always kept a distance from them, even as they greatly admired him. He refused, for instance, to exhibit in any of the Impressionist exhibitions because he always sought recognition at the official Salon.

Incomparable Impressionism features two paintings that depict Victorine Meurent (1844-1927), Manet’s favorite model of the 1860s. The portrait illustrated above (which is slightly cropped on the sides and at the top) was the artist’s first depiction of Meurent. She also modeled the nude figures in Manet’s two most famous paintings: Olympia and Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (both painted in 1863 and in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris). One can see qualities in this portrait that disturbed contemporary viewers: Meurent looks directly at the spectator (this look was considered brazen in Olympia); her skin is also rendered in a very stark, abbreviated manner. It is as if she were blasted by a flash: a bright, flat area shifts abruptly into shade, without traditional half tones to make the transition from light to dark.

Edouard Manet, “Street Singer,” c. 1862, oil on canvas, and “Victorine Meurent,” c. 1862, oil on canvas. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Manet witnessed a street singer emerging from a lower-class café. She reputedly refused to pose for the artist, so he reenacted the tableau with Meurent in his studio.

Edouard Manet, “Street Singer” (detail), c. 1862, oil on canvas. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

As she passes though swinging green doors, the woman eats cherries with her right hand. With her left hand, she simultaneously clutches her guitar and lifts her skirt, all the while securing the parcel of cherries in the crook of her left arm.

The casual instantaneity, the blurring of the lower portion of the dress-in-motion, the “low” subject matter, the somber colors, and the blankness of the ground have precedents in the art of Diego Velázquez, who Manet would single out as the painter of painters on his trip to Spain in 1865. (For a brief discussion of Velázquez’s hold over Manet, see Peter Schjeldahl on the Manet/Velázquez exhibition in The New Yorker.) Spanish painting was lionized by modern painters in France and other countries because it offered an alternative to academic painting. One can see echoes of Manet’s works such as Street Singer in Renoir’s Dance in Bougival.

Other major paintings for which Meurent modeled for Manet include Mademoiselle V. . . in the Costume of an Espada (1862, Metropolitan Museum of Art), Young Lady in 1866 (1866, Metropolitan Museum of Art), and The Railway (1873, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

Meurent was also a painter — a more traditional one than Manet — who exhibited in several Salons. After much research, at least four of her paintings have surfaced, all in the last two decades. See: Drema Drudge, “Victorine Meurent, More than a Model,” Art Herstory, March 31, 2020.

Incomparable Impressionism provides a rare opportunity to view a large body of Impressionist works in the context of their predecessors and successors.

Incomparable Impressionism was co-curated by Katie Hanson and Julia Welch at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It was organized at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts by Helga Aurisch, where it is on view through March 27.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator. He reviewed Ernesto Neto’s installation SunForceOceanLife at the Houston MFA in Glasstire on August 14, 2021.