Food is an underrated political flashpoint. From hunger strikes to discussions of cultural appropriation and classism, the issue of food and who has access to it is intertwined. This is true when we turn our attention to the prison system, as well; for those of us who haven’t been incarcerated, there is a cultural fascination in what life is like “on the inside,” and that includes inmates’ access to food. In pop-culture’s depictions of prison in TV shows (Prison Break, Orange is the New Black, The Night Of, etc.), podcasts (Ear Hustle), and other media, the stories always at some point address prison food. We understand and relate to it, and it’s often a loaded topic in an inmate’s experience.

The Last Supper: 700 Plates Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Death Row Inmates installation view at Texas State Galleries (click to enlarge).

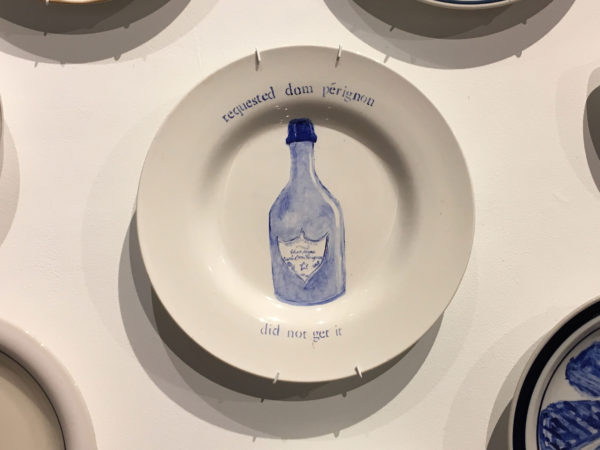

Julie Green, an Oregon-based artist, combines our familiarity with food and our fascination with prison life in her exhibition The Last Supper: 700 Plates Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Death Row Inmates at Texas State University’s Galleries in San Marcos. As the title states, the show is comprised of 700 kiln-fired ceramic plates installed in a dense horizontal band across the gallery’s two rooms. Each dish depicts, as interpreted by Green after reading a prisoner’s request, a rendering of the death row inmate’s last meal. From a distance, the show is uniform; all of the white plates are painted with a blue pigment that echoes refined blue and white Chinese porcelain, but the project has a conceptual weight that emerges once you begin to consider the plates as individual objects.

The Last Supper: 700 Plates Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Death Row Inmates installation view at Texas State Galleries (click to enlarge).

Green has been working on this series since 2000 when, while she was working at the University of Oklahoma, she noticed an inmate’s final meal request in the morning paper. She began collecting and painting pictures of the meals described, and later searched for the meal requests of inmates in other states. Before Green starts each painting, she considers what sort of plate makes sense for the meal — prisoners who eat nothing get small, unadorned dishes, and those who ask for the whole shebang get platters bigger than your head. As an ongoing meditation and protest against the death penalty, Green plans to add fifty plates a year until state-sanctioned executions are abolished.

The Last Supper: 700 Plates Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Death Row Inmates installation view at Texas State Galleries (click to enlarge).

The Last Supper’s return to Texas, (it was shown at DiverseWorks in 2007), is a macabre homecoming of sorts. The Lone Star State has executed the most people of any state, by far, since 1976. (Texas is number one at 543 executions; Virginia is second at 113.) Texas is also the only state that doesn’t allow inmates to request a customized final meal. In 2011, after an inmate asked for and then did not eat an extravagant final meal, Houston Democratic State Senator John Whitmire called for an end to the practice. Now, Texas inmates receive the day’s standard prison meal.

The Last Supper: 700 Plates Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Death Row Inmates installation view at Texas State Galleries (click to enlarge).

The paintings in the series have a portrait-like quality. While we may not know the inmate’s name, we know three key details about their life: where they were killed, when they were killed, and how they chose to spend their final hours. Food and the act of eating is intensely personal, and through the meals of these death-row inmates, we learn more about who they were. Preferences emerge, and it’s clear that these meal requests are about more than food. They’re about comfort. One prisoner in Louisiana asked for “fried sac-a-lait fish, topped with crawfish etouffee, a peanut butter and apple jelly sandwich and chocolate chip cookies.” Since fish with etouffee and an apple jelly sandwich don’t go together, we can’t help but infer that this prisoner was harkening back to their childhood — to a life at home — in their attempt to recall a kind of freedom one last time before dying.

Julie Green, Louisiana 07 January 2010, Fried sac-a-lait fish, topped with crawfish etouffee, a peanut butter and apple jelly sandwich and chocolate chip cookies. 2010, 8 inch diameter.

Texas’ elimination of this choice comes through quite clearly in Green’s plates — it feels like these prisoners after the 2011 decision are further away from us; we don’t know who they are, and they’re more of a number than an individual. This is the penal culture that Green’s show is explicitly resisting. It’s easier to overlook people being killed in state-sanctioned executions when they are just numbers on a page. It’s much harder to ignore the system when you humanize an inmate and grasp him or her as an individual.

The Last Supper: 700 Plates Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Death Row Inmates installation view at Texas State Galleries (click to enlarge).

Green’s The Last Supper successfully politicizes our fascination with prison life and a person’s choice of food. The plates, though at first charming and unassuming, introduce us to people that we may otherwise pass over, and force us to consider the inmate’s humanity through the common denominator of food. If this series makes even one person reflect more deeply on the current system of capital punishment, Green has done her job. And with the ever-decreasing drop in number of death sentences and executions across the nation, hopefully Green’s project will soon come to a close.

“The Last Supper: 700 Plates Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Death Row Inmates” is on view at Texas State University through November 10.

2 comments

What did their victims eat for their last meal?

Since Julie Green is so interested in food as an “underrated political flashpoint” she starts painting the food contents of murder victims cataloged during autopsy “as an ongoing meditation and protest against” murder? I’m sure she could add many more than fifty plates a year.