As we artists grapple with how to appropriately respond to or contend with the new reality in which we live, I also find myself—as a critic and a viewer—reevaluating what my expectations are when looking at art. While it is my personal belief that like a slow-moving tectonic plate, art molds and changes the world, I don’t need or expect or even necessarily want the individual works I’m engaging with to want to change the world, or even try. But as I traverse in and out of various art spaces, I find myself starving for sincerity and increasingly impatient with work that lacks it. So I found myself pleasantly surprised—touched even—by Robert Ruello’s latest work at Inman Gallery in Houston.

I say surprised because at first glance, Ruello’s modus operandi could read as a post-modernist, post-internet one-liner that any of us have seen a hundred times: pixels or manipulated images from the internet rendered by hand. But regardless of the path he takes to realize the work, he expertly averts such dismissal by employing quiet-yet-potent moments of visual investigation and formal dynamism.

We feel this most cohesively with Reflect #4 (2014). An orange roller coaster spinal column barrels vertically down the middle, enticing us to dive head-first into a glimmering concrete-looking pool below. It doesn’t really matter here where this image originated, and it’s neither here nor there that it derives from a computer. But what does come through—and what I think Ruello is really after anyway—is the simultaneity in the obliteration of one image that generates a new and different kind of formal engagement.

Similar in size but broader, Reflect #2 (2015) is more flat-footed. While Reflect #4 ruthlessly yanks our eyes down like a spinning wheel, with Reflect #2 we become mesmerized by the shiny trapezoid that harbors bleeding paint and a razor-thin horizon line of reflected gallery lighting at its top. The problem is there’s nothing else in the painting to be mesmerized by: it all plays second fiddle to the lovely and dramatic murkiness occurring within that compacted space.

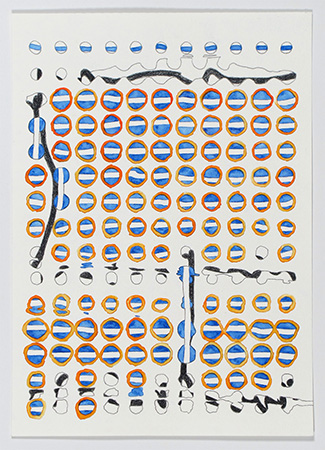

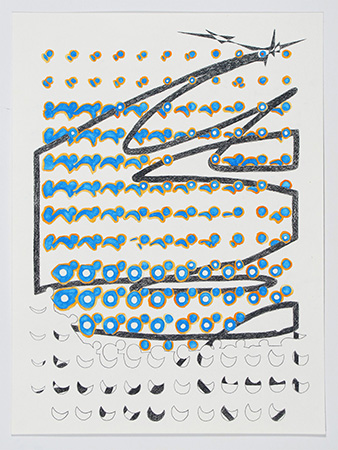

The real stars of the show are the smaller works on paper, particularly the row facing Reflect #2 on the opposite wall. Most of these works largely abandon the expressive, seemingly gestural abstraction so readily apparent in the larger paintings in favor of a stuttering, SOS dot system. From afar they read as hieroglyphs or a broken binary language, and as they slowly and quietly lead us in, we once again return to the showiness Ruello so clearly loves—playful decisions that display spontaneity, yes—but it’s an intentional spontaneity delivered with precision and care.

Sometimes Ruello’s measured spontaneity, particularly in the larger paintings, can come off as flashy and lean toward graphic design, which ultimately reads as more distant, more plastic, less relatable. With the smaller works on paper, particularly in Switch-it #3 (2016), he relinquishes more control to the viewer by not trying to grab us immediately with pushy complementary colors, and instead trusts that we will approach the work on our own accord. And the payoff is deeply gratifying as our eyes pore over the way the watercolor pools and clashes against the sharp outline of a circle, as we jump to aggressive chicken-scratch pencil marks that, as we zoom back out, fall back into a meditative white noise. We alternately gaze through circular tapeworm portals that pop back out into striped, oceanic eggs.

So many artists I think in this point in history feel compelled to respond to, or resist, or protest, or do something, anything. But as what seemed unthinkable six months ago becomes our new normal, artists like Robert Ruello make me wonder instead if basic human connection through the visual and aesthetic (authentic connection between a viewer and an artwork)—if an artist making a compellingly simple, vulnerable proposition for our time—can be enough.

On view at Inman Gallery in Houston through June 3, 2017.