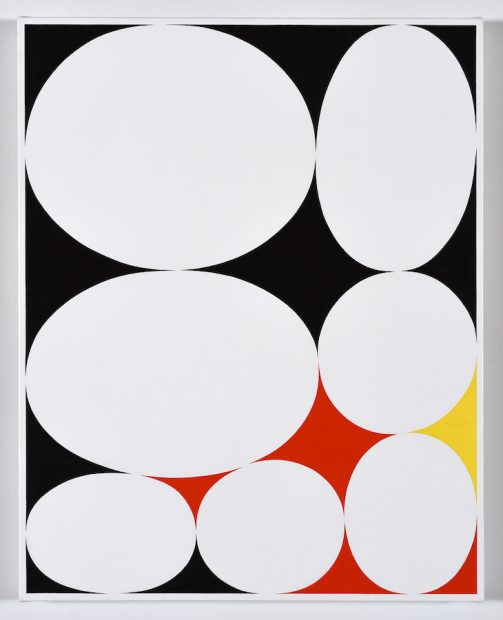

Installation view of Cary Smith’s solo exhibition “Like Ripples on a Blank Shore” at Inman Gallery, Houston, 2020

Turning to art in times of emotional distress is hardwired into a certain percentage of us, and I believe that makes us the lucky ones. When my father died suddenly and tragically I was working full-time as a critic in NYC and writing for a weekly publication, which meant being perpetually on deadline. Taking a long break to fully mourn was hard for me. Ten days after the death I decided to “return to work.” I attended a press preview for Ellsworth Kelly’s retrospective at the Guggenheim, not even sure for whom I would be writing. It was a perfect choice for me, as the Gugg’s legendary rotunda felt like the most sublime cathedral of pure beauty. In Kelly’s paintings’ sensual yet reductive perfection I was reminded of the profound pleasures we receive through the eyes to connect us to higher planes of existence. When I met Kelly the great master artist a few years later, I thanked him for providing spiritual succor to a wounded heart and he knew exactly what I meant.

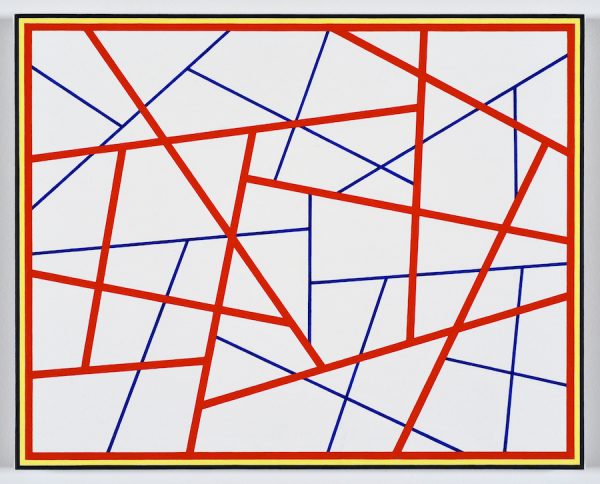

Installation view of Cary Smith’s solo exhibition “Like Ripples on a Blank Shore” at Inman Gallery, Houston, 2020

I thought of that magic that is only possible when art objects are physically placed before human eyes when I made my appointment for safely viewing Cary Smith’s marvelous exhibition, Like Ripples on a Blank Shore, at Houston’s Inman Gallery. I have known Smith’s work well since he started exhibiting in 1987, first showing his work in a large survey of contemporary abstraction at White Columns in New York.

Back then, the Cary Smith effect happened quickly and appeared to enrapture the entire downtown art world. As White Columns was known as a place for emerging artists to have first shows, a large percentage of the audience were gallerists trying to find new talents and every dealer asked for Smith’s number. More than a few were dismayed when informed he lived in rural Connecticut. Surrounded on White Columns walls by much better-known artists who had enjoyed magazine-cover recognition, this sweet, likable, regular guy from Connecticut stole the show.

The comparison to Ellsworth Kelly goes deeper though, as both artists seem as if their work should be fully apprehensible when experienced on a computer screen or phone. They both make hard-edged, brightly colored abstractions that are optically punchy and vibrantly hued. But with both artists, the details that shift the experience from pleasant to sublime are only apparent in the flesh.

Kelly’s use of scale in relationship to the human body and the room changes a simple graphic statement into the type of ethereally beautiful experience that can change you. The Holocaust museum in DC uses a four-part Kelly work for just that purpose — to spiritually recenter visitors shaken by the horror of human brutality.

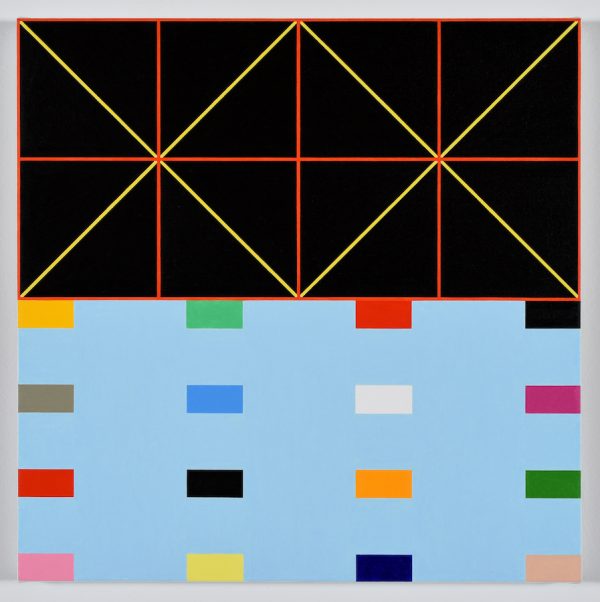

Smith’s paintings are more demure, and playful. After several decades of making signature paintings mixing grids and biomorphic forms, his work today often toys with self quotation, depictions of his older works slipping into the edges of new ones. This new technique of letting motifs reappear he calls “infiltrations,” and it’s what is “new” for his fans in his recent shows. Smith adds new motifs or colors very slowly, and some of the basic shapes and compositional crops have hung around his studio for decades.

Installation view of Cary Smith’s solo exhibition “Like Ripples on a Blank Shore” at Inman Gallery, Houston, 2020

Yet it is the one-two punch of his subtle choices as a colorist and his luxuriously soft surfaces that really lick the eye of an aesthetically refined viewer.

For sure his surfaces are nothing you can see on a screen. And one would think the color is difficult to mechanically approximate — it’s where reproductions fail Smith. The human eye’s sensitivity to color is such that the colors that backlit screens can show us are limited. And paint, photons and eye together provide pleasures a screen cannot. In a culture that forces many of us to stare at screens all day, chafing at their technologically reinforced limits is healthy. Screens alter vision, and Smith’s paintings can re-educate weary eyes.

I am of course a hypocrite, because while writing this is have all four of my Apple devices purring with Smith images, videos and texts about him. The gallery has on its website a quite marvelous video walk-through, with gallery director Michael O’Brien, that allows you to hear the artist’s no-nonsense voice and hear his personal names for his motifs. Still, the experience in-person is what haunts me, not the screen images.

One lineage of pure abstract painting aspires to the non-referential condition of music, and Smith has in the past posted videos of him painting to Bach, and revealing some of his studio tricks. (Among hard-edged painters, he is rare in not using tape but instead employing a mechanical drawing device.)

The title of this show, Like Ripples On a Blank Shore, comes from the Radiohead song Reckoner off their classic 2007 album In Rainbows. Smith has used Radiohead lyrics many times and feels a strong connection to Thom Yorke’s poetry.

Having seen Radiohead six times, when looking at Smith’s new work I harkened back to those in-person experiences and mourned that live music in any form many not return as a safe cultural activity for quite awhile, and I mourned for all the brilliant live arts in this city on indefinite hiatus — all the dancers, actors, playwrights, comics, singers and musicians whose art form has been taken from them though no fault of their own. I am even mourning the loss of museum blockbusters — the art experience we all love to hate.

Yet artist’s studios are churning during lock down, and galleries are easy spaces to social distance. Acclimating to exhibitions without crowded openings, and the artists’ talks viewable only on Instagram TV or Facebook Live is a small price to pay to enjoy experiences as spiritually fulfilling as Cary Smith’s Like Ripples show.

Extended through May 30. Currently, Inman Gallery in Houston is open by appointment only. Please call the gallery at 713-526-7800, or email at [email protected] and they will be more than happy to meet you at the gallery.