Your Middle Class Is Showing (middle class), 2016. Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum.

Emily Peacock, out of Houston, is primarily a photographer but that’s really too narrow. In her delivery, she’s a focused and precise artist, but trying to define her viewpoint or politics through her medium is futile. She’s too limber and curious to be fenced in. She is however, primarily a humanist with a sharp sense of humor and an appreciation for low-hanging absurdity.

Her show at Beefhaus in Dallas, User’s Guide to Family Business, follows fast on the death of her mother, who Peacock says was her best friend and collaborator. Grief and memory are on order here in photos, video and sculpture—but it’s all elliptical and never flat-footed—and considering this is the most emotionally loaded show of Peacock’s output at this point, it’s also a great example of how an artist can reframe the highly personal as art. At a moment most would forgive an artist for navel gazing, this is not a self-indulgent show. Peacock is generous with her audience. It’s like having a kind of storytelling prowess, and it’s gratifying to see an artist get wiser and stronger with every turn. She’s a true stylist, and I mean that in the best sense.

She’s still dealing with some of her previous concerns (and her devil really is in the details): the messy corporeal, family attachment, prosaic signs of middle-class existence, and troubled nostalgia. She plays with expectations not by hitting you over the head with smart-aleck taunts but with a quieter menace. But the work here isn’t scary, exactly (her previous work has flirted with creepiness); it’s warmly… calculated. She knows to be specific and personal enough to connect with the viewer—she’s tapped something crucial in her own weird angle on the human experience—but she makes it glossy and punchy enough for us to consume. There’s some Mike Kelley in that.

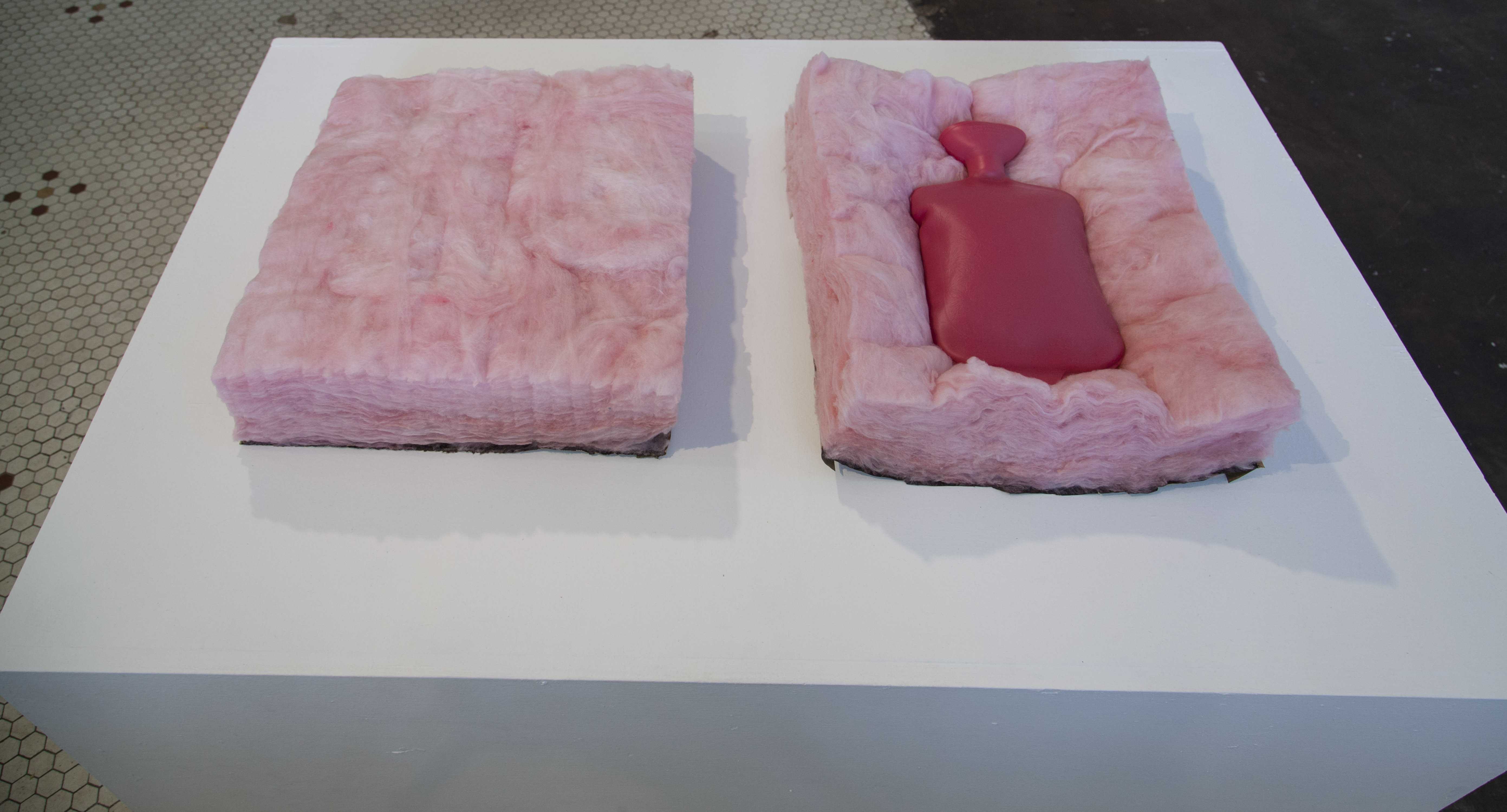

Creature Comforts, 2016.

Insulation and enema bag.

L: Intended to Give Assistance (Gloves), 2016. Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum. R: For the Groundbreaking Ceremony, 2016. Flocked shovel.

Peacock is in fact a master of handling the sentimental in a tough, cool, and distinctive way. Emotional content for her (including an enema bag, which one assumes is an object Peacock became overly familiar with when she was the main caretaker of her dying mom) can be both more poetic and palatable and—counter-intuitvely—much stronger when an artist recontextualizes it outside of its natural setting. Here the bag is nested in a fat, rectangular diptych of pink wall insulation, and this simple juxtaposition allows associations with dark and quiet and claustrophobic sick rooms, and the messiness of body fluids in a place better left dry. Bringing it all back home, so to speak. There’s a black, hand-flocked shovel leaning against a wall. It’s so dense and velvety you want to stroke it, but it really is its own slim black hole of a funeral, and it vibrates with loss.

L: Given the chance, I’d like the opportunity (circle, Im Sorry), 2016. Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum. R: Last Family Portrait with Mom (one with red overlay), 2016. Archival inkjet print with acetate overlay.

Much of the work in the show is photography. I like that here at Beefhaus, Peacock, instead of making every photo the same size and framed the same way, honors each image instead with whatever kind of frame or presentation suits it and expands its meaning. There’s a photo of cotton swabs arranged on a flat marbled surface; they’re caked in earwax and abjectly bent into the words “IM SORRY.” The image is mounted on a panel and cut into a circle and sits on Beefhaus’s beat-up floor. In a photo of Peacock’s own soft midriff, reverse-sunburned with the stenciled letters “Middle Class” (in gothic text, no less), the picture frame is a powder-coated fire-engine red. She’s an accomplished photographer and her references are lined up behind her like a personal greek chorus: in the wings I see Angus Fairhurst and early Sarah Lucas, William Eggleston and Richard Billingham. Some Arbus as well.

Peacock does compose and mitigate her images. In one standout, a photograph called Last Family Portrait with Mom, the remaining Peacock family members (Emily and her sister and dad) stand on a beach in their swimsuits, holding the box of Mom’s ashes. Peacock has placed the family behind a big square scrim of red acetate, and through that hot haze you can see her clutching the camera’s shutter in one hand. They are all, fittingly, wearing sunglasses.

Survival Kit, 2016.

35mm Slides in slide viewers, shelves.

There’s an old vault at Beefhaus and it’s always interesting to see what artists do with it. Peacock here has made what’s possibly her most precise and detailed work to date. The tiny space is blacked out, and mounted on one wall of it is a light box featuring tidy shelves of slides in their viewers, with each slide framing one to-scale item from a survival kit. A razor blade, a needle, a whistle, a compass; there are 12 in all. The backgrounds of each slide are either red or black, so it creates a glowing checkerboard. It’s incredibly elegant and more than a little disturbing. You’re staring into a taxonomy of neurosis, often a type passed down from parents to their kids.

For a Limited Time Only, 2016. Three-channel video.

There’s also a room where Peacock finds a mesmerizing intersection between her photography and video work. In the gallery’s second main space, three vertical video monitors loop images—portraits in motion—of three different childhood night lights that work like updated lava lamps. These were the ones Peacock had in her room growing up. Here they’re far larger than life and as hypnotic as fish tanks, with background color offsetting them like right-now Op Art, and the night lights seem to move in and out of shadow as though moonlight or sunlight is roving across the room they’re shot in. It’s a close, fond memory in motion, but made universally visually appealing, and through them Peacock and her viewers can sink into the rhythm of beginning and ending a day, but under the condition that it’s all faster than you want it to be, and relentless. We can’t stop it and we can’t walk away, and maybe that’s okay.

1 comment

I may not always agree with her perspective, but we are always lucky to have Christina Rees in Texas. She’s awesome! And this review is spot-on.