While there’s certainly widespread respect for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, one doesn’t necessarily expect to discover entirely new territory there, nor to be floored by contemporary relevance. The exhibition For a New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968–1979 changes those expectations. The show, which opened last month and is on view through mid-July, surveys a fascinating history of experimental photographic works previously little-known outside of Japan. Its smart, diverse assemblage activates raw evidence of revolutionary shifts in medium and methodology as Japan entered a time of postwar political and social turmoil (along with most developed countries), and as photographic media first entered the art world in a major way. Most of the hundreds of works in the show have never before been seen in the U.S., and none of them have been widely shown here. To most, myself included, this reveals for the first time a missing link—an alternate history that’s both completely new and relevant, while retroactively expanding more familiar histories of the era’s cultural shifts and art world developments. Simply put, it’s one of the best shows of the year, anywhere. And I’m not the only one with that opinion.

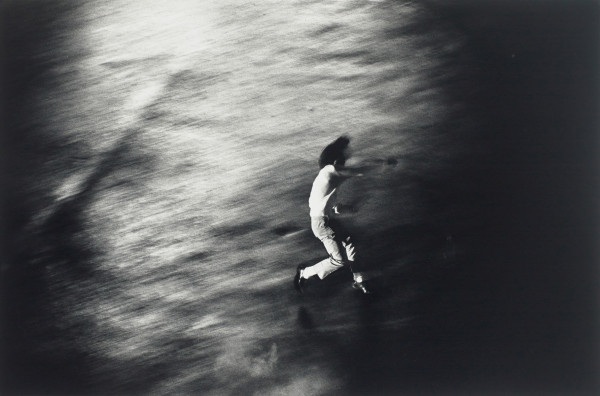

Shōmei Tōmatsu, Protest 1, from Oh ! Shinjuku, 1969, gelatin silver print, printed 1980, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the S. I. Morris Photography Endowment and Morris Weiner. © Shōmei Tōmatsu – INTERFACE

For a New World to Come opens with a strong, concentrated blast of work from the turbulent late-1960s. The raucous video collage, For The Damaged Right Eye, beckons and disorients visitors immediately at the entrance, evoking the conflicted impulses of Tokyo’s Shinjuku neighborhood at the time. Its assaultive blasts leave image fragments and cut-up pop songs lingering as one enters a gallery dense with black-and-white photographic prints, publications, and layered context clues. Charged glimpses of a Japan in flux emphasize the grain of the medium, the blurs of movement, and the framings of unsettled, subjective involvement in the rapid remaking of cultural and physical landscapes. Most of these capture spaces, street scenes, student protests, and subcultures in Tokyo. Images from advertising and television are present in some of them—seeming like the first trysts of a complicated relationship to come between photographic environment and photographic artist. Among the many independent publications on view are issues of the influential photo journal Provoke—artist-curated assemblages of disquieting images, each printed full-bleed to the edges of its page and crashing into the next.

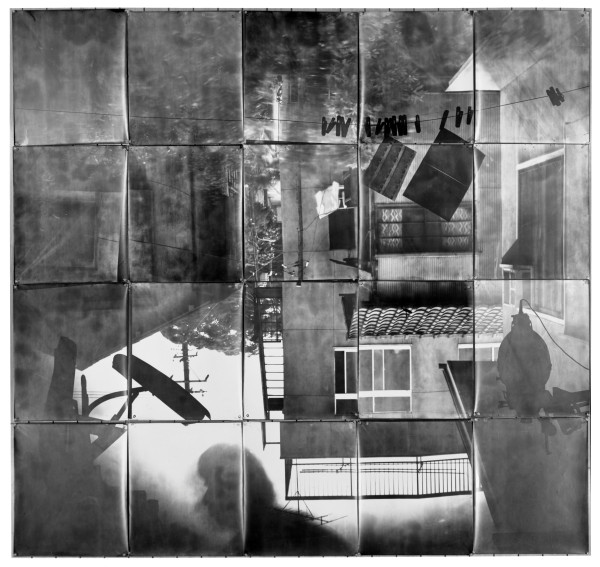

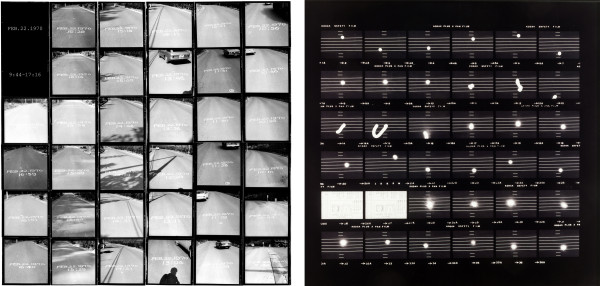

Just this smallish first gallery of late-1960s work would be an impressive exhibition on its own, but here it serves as an explosive prelude to a bigger show of work made over the following decade. Larger, lighter gallery spaces contain a wide variety of photographs, installations, videos, paintings, and sculptures—generally more contemplative, conceptual, and existential explorations of and through the medium. Jirō Takamatsu’s Photograph of Photograph is among the simplest images on view. But, especially in the context of this show, its light reflections atop a photo pinned to wood seem to offer a complex and poetic reflection of our relationships with physical photographs. Nobuo Yamanaka’s Pinhole Room Revolution 1—the result of the artist turning his apartment into a giant pinhole camera and exposing an entire wall tiled with photographic paper—has a similar, simple profundity in its reflection of the inverse relationships of image and photographer. There are a number of strong, more formal projects by artist Hitoshi Nomura, including his Time On a Curved Line which chronicles in increments his movements along a road.

Nobuo Yamanaka, Pinhole Room Revolution 1, 1973, gelatin silver prints, the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. © Nobuo Yamanaka

During my first visit to the show, I paid little attention to wall labels and simply let the works speak to me and to each other. I appreciate that its design allows this, and I recommend it. But a later visit and conversation with organizing curator Yasufumi Nakamori gave me a little better grasp of its underlying trajectories and I realized an important through-line in the endeavors of one particular artist. In 1968 (the first year of this survey), photographer and media theorist Takuma Nakahira was involved in research for the exhibition Photography 100 Years, which creatively examined the intertwined histories of modern Japan and photography. The same year, he joined three other photographers and a poet in producing the influential Provoke publications, signaling a radical departure from conventional photographic approaches. His photo book For A Language To Come (which the exhibition’s title references) comprises a number of his late-60s images and asserts that the appropriate language for the time was a photographic one.

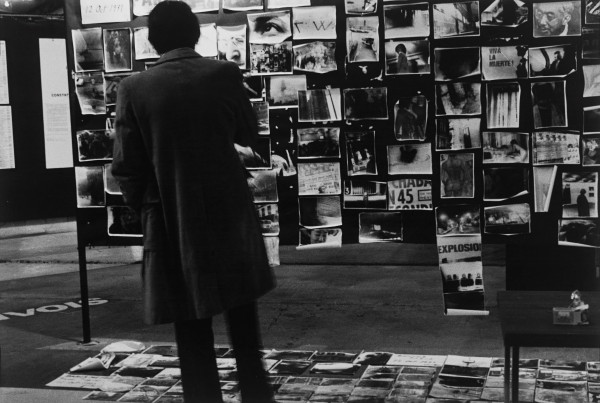

Takuma Nakahira, from Circulation: Date, Place, Events, 1971, gelatin silver print, printed 2012, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by Joan Morgenstern, Peter Lotz, and Photo Forum 2013.

For Nakahira’s contribution to the 1971 Paris Biennale, he prepared nothing in advance, but rather presented an evolving display of photographs taken each day in the streets of Paris during the show. The process-based installation, Circulation: Date, Place, Events, reoriented fragments of the city outside, and eventually expanded to the floor and across the boundaries of his allotted exhibition space. A version of this piece is prominent in the show, as is his Overflow—a large piece comprising 48 different color photographs that was created for the 1974 Tokyo exhibition “Fifteen Photographers Today.” While its Japanese title, Hanran, means “overflow,” it’s also a homonym for “revolt” or “rebellion”—a nuance that nicely reflects both environment and concerted intervention. The seriousness of Nakahira’s experiments in the re-mediation of everyday images is expressed in the proclamations of his book, Why an illustrated botanical dictionary?: “The city has shaken each of our identities at their foundations. Our everyday selves are continuously inundated by a flood of commodities, a flood of information, and a flood of material things…We must dare to turn the tables.” While this survey doesn’t tout a singular philosophy, movement, or leader, Nakahira’s continual consideration of the potentials of photography as a means for destabilizing and reorienting existing cultural flows is clearly at the heart of the show. And thinking about his works—all of which are concerned less with single images as they are with the assemblage of many—helped me to identify something I find really compelling.

Takuma Nakahira, Overflow, 1974, chromogenic prints on panel, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

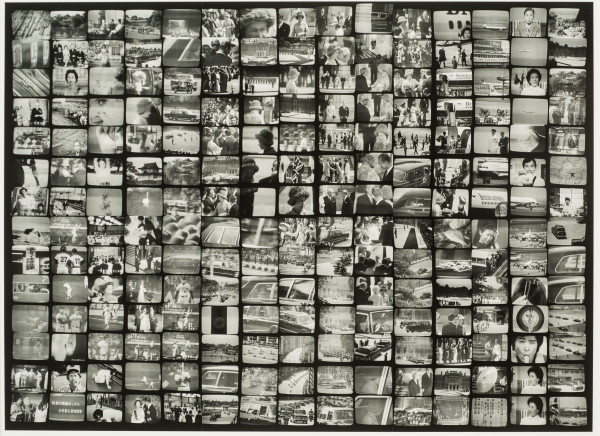

A common thread across the wide range of works here is the use of multiple images. Some contain multiple images within a frame, others assemble series. Some create a montage of frictions, reflecting multiplicity and simultaneity. Others show increments of actions and experiences, exploring duration, change, movement. Actually, nearly all of the work in the show could be considered series. The photographic process is essentially serial by nature, and curatorial. It occurs to me that photographers’ increasing engagement in the creative selecting, compiling, and arranging of multiple images during this time may have been key in the acceptance of photographic media by the art world in general. It also occurs to me that this exhibition is, itself, a similar assemblage—a series of series. Curator Yasufumi Nakamori has taken cues from the work and its era to focus less on certain artists or approaches than on creating a dialogue between a variety of simultaneous and overlapping experiments that occurred in those dozen years. I think it’s the various activations of the in-betweens here that so well evoke the concerns of the time, and also so strongly relate it to current culture. In many ways, 1968-79 was an in-between period of time in modern history, and one not dissimilar to the one we’re in right now.

Above: Masao Mochizuki, Queen Elizabeth in Tokyo, May 7, 1975, from Television 1975–1976, gelatin silver print, printed c. 1998, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund. © Masao Mochizuki

Left: Hitoshi Nomura, Time on a Curved Line, 1970, 34 gelatin silver prints, the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. © Hitoshi Nomura. Right: Hitoshi Nomura, ‘moon’ score, December 19, 1975, 1975, gelatin silver print, printed c. 1995, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

I’m barely scratching the surface of a great discovery here. The show is in no way as narrow as the paths I’ve begun to carve. It’s a fascinating and accessible exhibition, providing a diversity of inroads, and affording as many freedoms for the viewer’s own experience. I recommend at least one visit to its premiere engagement at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston before it comes down and travels to New York. For a New World to Come is currently on view through July 12th. In addition, the museum’s upcoming related screening of the rarely-seen 1969 Japanese film AKA Serial Killer (Friday, May 15) should be an interesting compliment to the show.

Peter Lucas is a writer and critic living in Houston.