Converging Lines: Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt is Veronica Roberts’s first major exhibition at the Blanton since joining on as Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art in February of last year. It’s a strong start that allows her to draw upon over a decade of experience––Roberts served as special projects coordinator for the 2000 LeWitt retrospective at the Whitney Museum and then as director of research for the LeWitt Wall Drawing Catalogue Raisonné––and it serves Austin well in providing a rare opportunity to view the works of two major artists associated with the vibrant and historically critical art scene of Lower Manhattan during the 1960s. Visually, the show is impressive: beautifully installed and smartly arranged, it presents a fine selection of drawings, paintings, and sculptures by both LeWitt and Hesse. But what’s more, and what makes this show significant to an art historical community outside of Austin, Roberts’s curatorial approach issues a challenge to the conventional (museum or academic) taxonomies of art from this period and encourages visitors to see what may be familiar forms of art in new and more interesting ways.

Sol LeWitt and Eva Hesse are among Art History’s biggest names. We could narrow the field to the latter half of the twentieth-century––and to New York-based artists, sure––and then refine it with a litany of art historical tags, like: “Modernist” and (…can one still say) “Postmodernist”(?), “Minimalist” and “Postminimalist,” “Conceptual Art” and “Process Art,” etc. For anyone who frequents museums of modern art or who has ever taken a basic art history survey, such tags are omnipresent––so much so, in fact, we may sometimes ignore how distorting they can be. Still, at this point, it’s hard not to engage them. Most often we encounter canonical artists, like the ones in this exhibition, as exemplars of supposedly distinct artistic movements. “Sol LeWitt” is not just an artist’s name; the name signals a pioneer of Minimalism and Conceptual Art; it connotes an artist principally concerned with concepts rather than craft, a systematic ideas man. In contrast, “Eva Hesse” signals another set of concerns: a pioneer of Postminimalism, an intuitive process of making––and investment in the physical act of making––as well as the biomorphic forms and fragile materiality of her sculptures; in short, intuition, body, process, antiform. So codified are these descriptions––diametrical in the case of Hesse and LeWitt––that a curator dealing with the artworks in a creative way will likely tend toward a revisionary approach. In Converging Lines, the revision is perhaps subtle; it comes in Roberts’s choice of pairing Hesse with LeWitt and in the nature of the motivation for that pairing. She brings together two artists connected in life and not so much in art historical narratives, thus grounding a presentation of their works in the stuff of lived history as opposed to the abstractions of Art History.

The show celebrates the close friendship between Hesse and LeWitt and aims to demonstrate the mutual influence that each artist had upon the other. As Roberts describes in the accompanying catalog, the show’s premise stemmed from her personal conversations with LeWitt while at work on his retrospective. She learned the back-story to his Wall Drawing #46 (1970), which LeWitt created and dedicated to his dear friend Hesse shortly after her tragic death from a brain tumor at age 34, in May 1970. The drawing, which provides both the physical and conceptual centerpiece of the exhibition, consists of “vertical lines, not straight, not touching…”

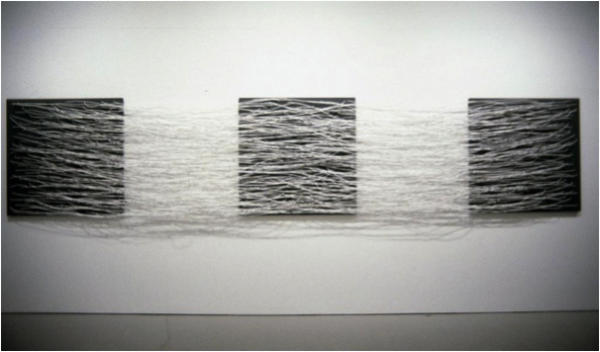

Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #46: Vertical lines, not straight, not touching, uniformly dispersed with maximum density covering the entire surface of the wall, 1970 (detail) Pencil on wall, dimensions variable. LeWitt Collection, Chester, Connecticut

The significance of the “not straight” line within LeWitt’s practice after 1970 stands, in the exhibition, to mark Hesse’s lasting influence upon his life and art. The organic lines contrast with the rigid, geometrical lines that typify LeWitt’s earlier practice, and, for him, they provided a means to integrate the organic quality of Hesse’s art within his own. One encounters Wall Drawing #46 in the second room of the exhibition, on a wall that moves visitors between the first and second rooms as well as the second and third (the artwork occupies three rooms and a fourth displays archival and didactic materials). It thus functions physically as a pivot, and visually, it provides the clearest evidence in support of the formal influence of Hesse’s art upon LeWitt’s. (If this direction of influence commands more emphasis within the exhibition than the other, it is because Hesse’s debt to Minimalism––and to LeWitt, in particular––has received due attention in the broader literature and thus a special aim of this exhibition is to demonstrate a balance.)

The objects’ arrangement within the galleries guides viewers toward the formal connections that Roberts hopes they will draw, and in the second room, those relationships are especially marked. Here, the optical patterning of the LeWitt grid meets Hesse’s tactile and biomorphic, even erotic, forms. We see Hesse’s drawings on grid paper––filled with tiny Xs and Os––alongside LeWitt’s grids and cubes, and we see the curvilinear quality of Hesse’s works become more pronounced, finally to culminate in a striking juxtaposition: Hesse’s sausage- or whip-shaped sculpture with a partially-severed tip (No Title, 1966) adjacent to LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #46.

Room 2. The wall that appears grey in the photograph on the right is LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #46 (1970). The reproduction of Hesse’s Metronomic Irregularity II (1966) hangs on the left-most wall in the photograph on the left.

“Not straight” lines resonate between the works and effectively imply the desired connection, but that formal echo is neither the only nor, perhaps, the most intriguing relationship among them. On the wall opposite Hesse’s “sausage” hangs a reproduction of her 1966 Metronomic Irregularity II, which she originally created to show in Lucy Lippard’s landmark 1966 exhibition Eccentric Abstraction at the Fischbach Gallery in New York. The reproduction presents an installation view from the Lippard exhibition, since the sculpture is now lost, and it appears oddly flat and out-of-place within the Blanton’s space. Nonetheless, Metronomic Irregularity II is an important work in Hesse’s oeuvre, and the exhibition placard makes a fine case for its inclusion, even in reproduction. Specifically, this work impressed LeWitt––who had assisted Hesse with the 1966 mounting––because he recognized in it an installation that would never be the same twice, an idea that also underlies his wall drawings in which assistants execute a design based on LeWitt’s instructions; both foster indeterminacy between intention and outcome.

Installation view of Eva Hesse, Metronomic Irregularity II, 1966. Painted wood and cotton-covered wire, 48 x 240 inches. Whereabouts unknown since 1971

The idea of indeterminacy is one that had a lot of currency during the 1960s––in John Cage’s influential “chance” methodology, for example––and should remind us that a focus on Hesse and LeWitt necessarily remains an art historical exercise, as artificial, albeit more productive at this stage than more conventional approaches to framing histories of art. For me, the most exciting aspect of the exhibition is all that remains bubbling under the surface; it is the way in which new configurations of objects begin to reach out into a past, unseen but suggested, subtly and sometimes not-so-subtly. Eva Hesse’s own descriptions of her work can help us to approach that past. She commonly used words like “absurd” and “ridiculous” and discussed contradictions that she perceived inherent in life and in her art:

I remember always working with contradictions and contradictory forms, which is my idea also in life. The whole absurdity of life […] in the forms that I use in my work, that contradiction is certainly there […] I was always aware that I could combine order and chaos, string and mass, huge and small. I would try to find the most absurd opposites or extreme opposites and I was always aware of their contradictions formally. [1]

In these words we hear echoes of a surrealist sensibility that also pervaded the Hesse-LeWitt artworld during the 1960s. Hesse loved the works of Öyvind Fahlström, Lucas Samaras, and Paul Thek, for example, and embracing contradiction or absurdity in her work, as well as aspects of eroticism and a haptic appeal, means recalling its embeddedness within a larger art historical context that included the works of these artists, among others. Even through Sol LeWitt, we can get to that place. [2] Exhibition viewers may be surprised to see LeWitt’s colorful, painterly, playful early works on display. I was, and among them I found two of my favorite works in the show. LeWitt’s early boxes, Lightbox (1964) and Cube with Random Holes Containing an Object (1964), both contain surprises (I won’t tell you what they are), but they hide as much as they reveal and provoke viewers to surmise their contents after numerous partial glimpses. The boxes recall Joseph Cornell, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg, for example; they invite us to touch and play; they’re delightful. Seeing LeWitt’s better known cubic constructions, such as 3 x 3 x 3 (1965) alongside his earlier boxes and Hesse’s works draws out their materiality as well as the physicality involved in viewing them, as they morph in response to the moving eye.

LeWitt, Cube with Random Holes… 1964; LeWitt, 3 x 3 x 3, 1965; Hesse, Accession V, 1968

But to suggest that the exhibition isolates Hesse and LeWitt from their art historical context would be unfair. The museum display explicitly reminds viewers of a broader context through the inclusion of a map that shows the locations of numerous artists’ lofts in Lower Manhattan during the 1960s as well as reproductions of postcards that circulated among the artists’ circle of friends. The map functions most effectively as a sign of the dense reality of everyday life, that ephemeral stuff that constitutes lived experience and is yet oh-so-very hard to name. How did the friendship between Hesse and LeWitt really influence their lives or art, beyond formal or conceptual echoes? We can’t know.

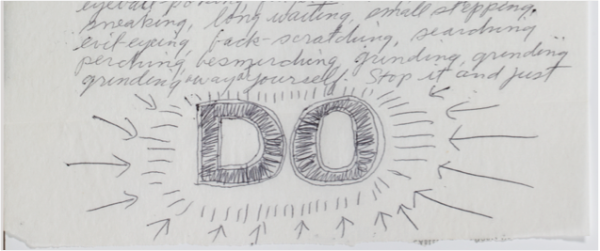

Sol LeWitt, letter to Eva Hesse, 1965, detail of page 1.

One of the show’s very special prizes is a five-page, handwritten letter that Sol LeWitt wrote to Eva Hesse in 1965. In it, he encourages her to have confidence in herself and in her art without worrying about how others perceive her. It’s the kind of encouragement every one of us needs now and then: “Learn to say ‘fuck you’ to the world once in a while. You have every right to,” and “Don’t worry about cool, make your own uncool,” are a couple of highlights. The letter evidences LeWitt’s famous generosity of spirit even as it simultaneously indicates a dark reality beneath the surface. To what extent did the fact that Hesse was a woman making art in the 1960s (before the rush of the Women’s Movement) affect her confidence in herself or in her art? Again, at this point, we can’t truly know, but one is rightfully skeptical of received interpretations of her work that fasten it to intuition, body, etc. and neglect the ideas that she also expressed. The taxonomies outlined above are historically formed and inseparable from specific assumptions about femininity and masculinity. Converging Lines offers a significant, alternative take on the works of both artists that encourages one to see potent ideas in Hesse’s work as well as physicality and absurdity in LeWitt’s. For this, and for insisting upon the importance of grounding the works in a space of everyday life, it deserves attention.

Robin K. Williams is a PhD candidate in Art History at The University of Texas at Austin. She studies interrelationships between the visual and performing arts, especially in New York during the 1960s and 1970s.

[1] From Cindy Nesmer, “A Conversation with Eva Hesse,” Artforum 8, no. 9 (1970); reprinted in Mignon Nixon, ed. Eva Hesse, (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002), p. 9.

[2] Veronica Roberts goes there in her catalog essay, “Opening LeWitts Early Boxes,” in Veronica Roberts, ed. Converging Lines: Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt (New Haven: Yale UP, 2014).