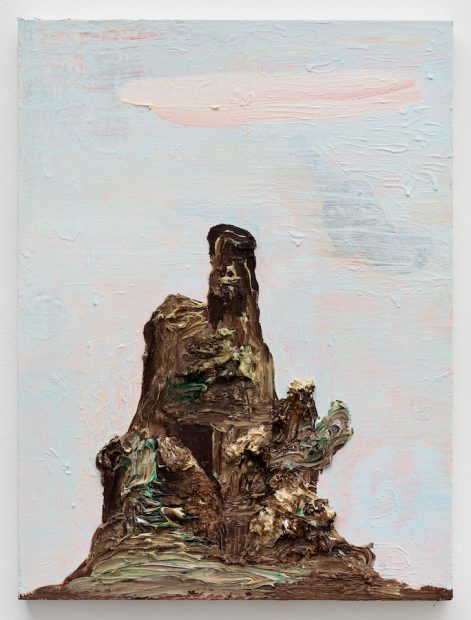

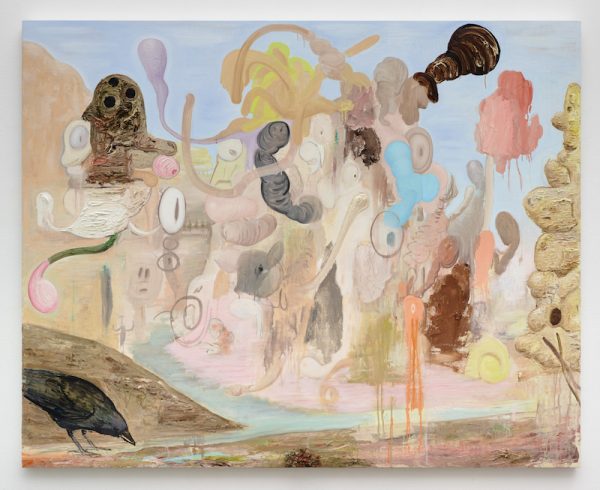

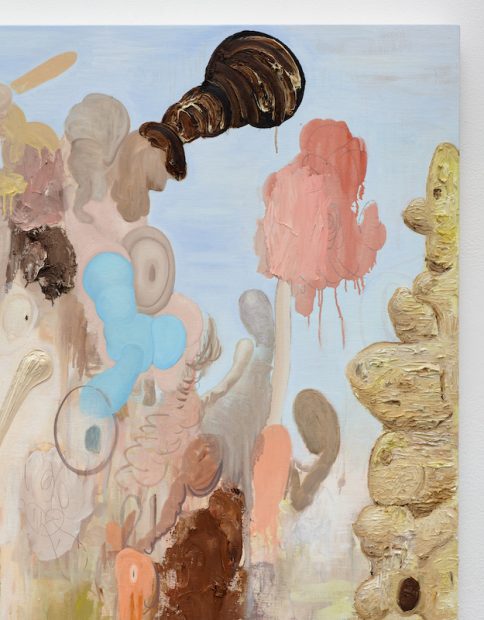

Victor Estrada,

Pink Cloud / Chocolate Mountain / Blue Sky with Shadow, 2017.

Oil on canvas over panel,

24 x 18 inches

An outsized landscape is the setting of Victor Estrada’s recent paintings: the sprawling desert lying between Los Angeles and El Paso. This land — all but empty it would seem — has a contentious history, from the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors and their murderous onslaught, to the crowds today chanting for a border wall.

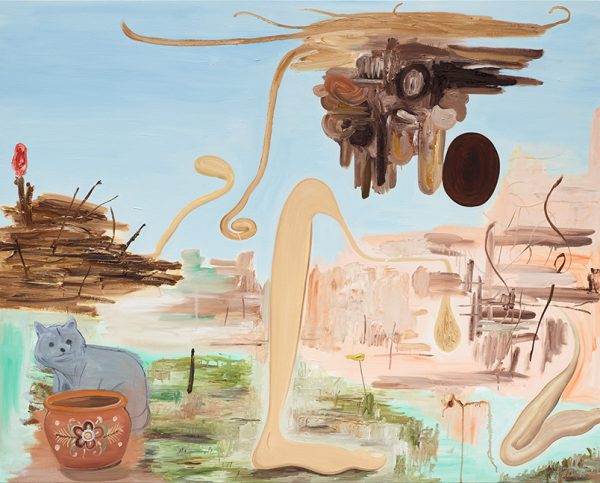

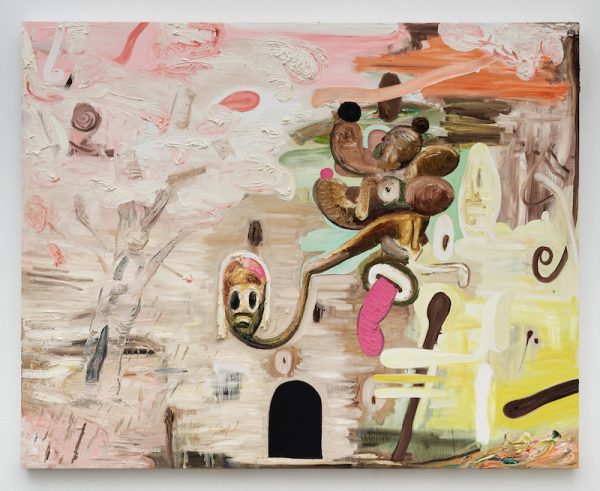

In Estrada’s paintings, the landscape is unfixed and ambiguous, “not host but ghost,” as curator José Luis Blondet puts it, in the catalogue for Casa Tomada, SITE Santa Fe’s 2018 edition of the SITElines biennial, which explores contemporary art of the Americas (on view through January 6, 2019). Teetering between figurative and abstract, in two of Estrada’s paintings on view, a jumble of body parts, cartoonish protuberances, and unidentifiable floating objects hang in front of the landscape, anchored by recognizable elements on the fringes of the canvas — a terracotta pot, a tree, a crow. A third, smaller painting depicts a more straightforward landscape: one of those stovepipe-shaped rock outcroppings typically seen in the Southwest. The paint ranges from wispy pinstripe to glommed-on, sculptural denseness.

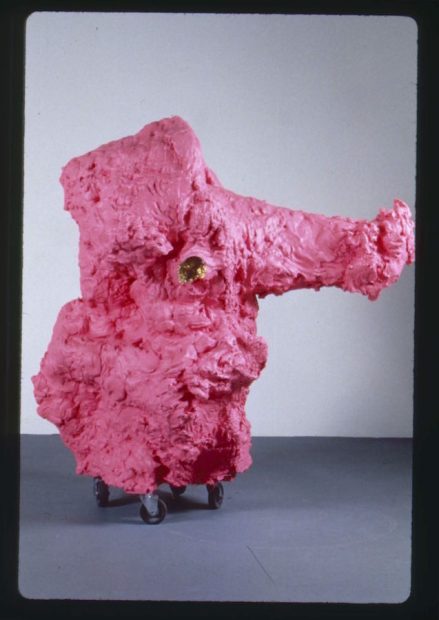

Victor Estrada, Baby/Baby. Installation view, Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990’s, 1992, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

Victor Estrada was born and raised in Los Angeles, where he still lives and works. His family and wife’s family live in El Paso, Texas, and he makes the trip from Los Angeles every year. “I have these two different locations where my self resides,” he tells me. As a young man, he studied for a time at the University of Texas in El Paso, and spent some time in Lubbock before pursuing his art degree at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California. Estrada’s museum debut took place in the influential Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990’s exhibition, curated by Paul Schimmel at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 1992, where Estrada’s massive foam sculpture, Baby/baby, attracted the critics’ attention. In March 2019, the Luckman Gallery in Los Angeles will host a comprehensive exhibition of Estrada’s work from the past three decades.

I met with Estrada at the opening of SITElines in August, where we talked about the tenuousness of identity, shifting subjectivities, and how physical sensations collide with psychological impressions in his painting. This was our conversation, which continued over email:

Victor Estrada: I think growing up [between Los Angeles and El Paso] I became more aware of the instability of self and identity, and that those things are constructed entities. They’re based on agreed-upon ideas. And in the United States they’re really framed by politics and conflict. The idea of a subjective experience gets displaced. I think that’s one of the reasons painting is interesting to me, because it lends itself to a very subjective experience. You’re less restricted by technical requirements, like a certain quality of weld. Painting is much more forgiving as far as technical aspects of it.

Natalie Hegert: You’ve done a number of sculptures, but your interest is mostly in painting?

VE: Well, even when I made sculptures they were an extension of painting. I started making these paintings with stuff coming off the painting, actual forms made out of papier mâché. I was making shaped canvases, too. That’s how they became three-dimensional objects. Another aspect of that was that all of these [works] were politically motivated. When I was in the Helter Skelter show, I built this pink sculpture called For MLK. For MLK is five feet by five feet by five feet, using a bust of MLK: I put an impression in the plaster, painted everything pink and covered the impression made by the bust with gold leaf. The specific political objective [I developed] with that piece — consciously, maybe unconsciously — was that there was this whole other aesthetic dimension that got released with the political legitimization of the African-American. All of this stuff became part of the culture because of [the Civil Rights movement]. It was there before, but it was underground, so to speak. So for me, that piece was important because of recognizing the aesthetic aspect [of culture and space]. Not related to the notion of beauty, but this thing that’s called “the aesthetic.”

NH: Is that piece related to the dialogues happening at that time, when identity politics were coming to the fore? Is that something you were responding to?

VE: Well, for me that started happening at the beginning of the Chicano movement. In art, identity was initially restrictive, because it was [defined around the] Chicano muralists’ work. Whereas [someone like] Santana, who had rhythms of the music that my dad would play — so, related to identity — but also broadened it out, bringing in Caribbean sounds, in a more organic process, that’s more open. That’s more of what I was interested in, some sort of subjectivity. Representation, [on the other hand,] is based on a static idea.

NH: Shifting subjectivities are more interesting, and closer to reality too.

VE: Yes, closer to a person’s reality. Here, [identity] is sort of forced upon you. It makes sense because of the prejudice in the United States. It also makes sense politically because to get something done you have to be organized as a group, and therefore you have to be named. But I don’t think that makes very good art, actually, at all. There’s the sensuousness of the material, for example, the colors, all these other things that are not easily classified, unless you have a really defined code of artistic practice — like, for instance, the Egyptians, who had particular measurements for limbs, or in the Renaissance, in terms of how religious iconography was depicted — but we don’t really have that. In the United States it’s all about your subjectivity as an artist… .

Victor Estrada, I Went Walking and She Threw Me a Look / aka “Froggie Went a Courtin”, 2017. Oil on canvas over panel. 48 x 60 inches.

NH: Let’s talk a bit about the content of the paintings that we have in the show here. In the painting, I Went Walking and She Threw Me a Look / aka “Froggie Went a Courtin” (2017), you were talking about the pot and the raccoon relating to a place in El Paso.

VE: Yes, it’s my father-in-law’s backyard. They have a lot of stuff back there. My wife and her sister, they just want to get rid of this stuff. It’s cluttered. He likes to collect things: tree trunks, this owl that’s hanging from a tree, plastic animals, a rabbit with one eyeball out. They’re just on this table, not arranged in any particular way. It’s not organized, or not “curated,” let’s put it that way. The aesthetic just comes out of having this stuff but not really developing it in some way. I just find it very, very interesting. In that one painting there are a couple elements I put into the painting to orientate it in that way and to create this space with these, in some ways “unreal,” plastic things. And in that same painting on the right side there are marks that are made with a pin striping brush.

NH: So that ties it to Los Angeles, too… .

VE: Yeah, and it’s tied to lowrider culture. There’s other things [that orientate the painting], like the sky. Once you pass Palm Springs, go up this incline and head into Blythe (California): it [refers to] that space. That space kind of stays the same all the way to El Paso. It’s a desert space. It’s very vast, massive, and interesting, with these incredible mountain ranges that you see. And you get really, really hot. To me, I see these sorts of things and the impressions I get from them collide with psychological impressions that I have, maybe from other things. They elicit other kinds of feelings.

NH: The way you describe that makes me think again of your father-in-law’s backyard, this collection of disparate objects colliding.

VE: Yeah, I guess I’m thinking of how to bring these things together with some semblance of coherence, even though I think it’s a very tenuous coherence. And I’m ok with that. I think the reality of life is, at least for me, always disappearing. You have your reinforcements that bring you back to yourself — like children, for example — but once you’re left on your own, and you’re just kind of there, you think, What do I do, what do I want to do? To try to find out, you have to connect with your mood, your emotions. I think that’s why we tend to identify ourselves with external things, like your job, where you live… . But identity is always tenuous. A death, loss of a job: those things can cause people to begin to question themselves. You know, when guys retire, they tend to die. They spend so much time identifying through a job that they forgot to identify through their actual material body. That’s what I‘m interested in, that material body — and when I say the body I include the mind in that, because I don’t think the mind is separate from the body. The body brings in all the sensations; in response, hormones get released. This thing that you call the mind, you try to operate it as if it is separate, to control it, but you can’t.

So, in painting, I don’t have a plan for these things, only a general sense; but they’re not abstract paintings, they’re paintings of something. I start off with something and I have to keep responding to it. Over and over again.

NH: You can definitely see that in this painting, Big Rock Candy Mountain.

VE: It is related to a hobo song from the late 1800s-early 1900s, that speaks to a hobo dream of paradise where there is no need to work and food grows on trees, as well as cigarettes, and the whiskey flows in streams, etc. The song later gets changed to a kids’ song with candy cane trees and lemonade streams, etc. There is a kind of religious materialism expressed in the song which I find central to the American psyche. Religion and materialism are bound up in evangelical Christianity. It’s not much for sacrifice or suffering or denial like Catholicism is. It’s a weird contradiction.

Anyway, the painting speaks to this desire of a magical mountain of plenty that everyone who comes to America is hoping to find. At the bottom of the painting is a river, of sorts, which I relate to the border between Mexico and the United States. People here in the U.S. are anxious to fulfill their dream, but it is realized in an abbreviated or distorted form. And death is always there waiting.

NH: That is extraordinary! So was Big Rock Candy Mountain originally going to be included in SITElines? Now that you describe the significance of the folk song, I’m curious what “Froggie Went a Courtin” is in reference to?

VE: Originally it was going to be included, which I think was a good idea, but later Froggie Went A Courtin was chosen. The song is old and originates from Scotland, I think.

I like that there is a mutation of the song over time; you can see it in these two versions of the song… one by Tex Ritter and the other by the Flat Duo Jets. That speaks to me of art and how meaning becomes encoded and changed as things grow, like love/desire, which lies at the heart of the song. So the painting is really about instability — even though the pot at the lower left seems to be of certain origin, the rest of the painting is in flux and it is hard to determine what is what.

NH: One of the curatorial premises of the exhibition revolves around the story of the stolen foot from the statue of Juan de Oñate—and there’s this foot in the painting. I’m sure that’s not what you were thinking of when you were painting this, but I wondered how do you relate to that story and that theme in the exhibition?

VE: Of dislocation?

NH: Yeah, and altering a monument, a taking back of history.

VE: Well I think that to take back history is to reclaim your agency, whether that history is personal or communal. I think that’s a difficult task, but it’s the task that we’re in, in some way. But you’re not reclaiming a history that is fixed. If you were to tell stories of a tribal nature and you are here in a space like this, it seems that those stories would have a hard time being able to lay claim to this space.

NH: To this space? [Motioning to the gallery.]

VE: Yeah, it’s kind of like Catholicism, with all these miracles and everything. How relevant are they to me? Other than some kind of conceptual understanding of whatever this thing is called God and the world, I don’t think they exist in the same way that they existed for people in the Middle Ages, for example, when we really did have a belief in miracles and people had visions and prayed for relief from illnesses. I mean, now the miracle is that you can go turn on a light switch and you have electricity. If you’re trying to reclaim this older history to fix it, I don’t think that’s very productive, but if it’s reclaiming it to reinterpret it, I think that makes a lot of sense. You want to have agency, a voice; you don’t want somebody else to tell you what this history meant.

The West has a very different history from the rest of the country. L.A. was there before the Pilgrims got here. You got all these Spanish things all over the place. You have Indian dwellings in Arizona. You have this north-south relationship that’s always been going on. This idea of putting up a border is like trying to deny all of that history. And you have these people saying, Go back to where you came from. This is the thing about Texas: it was part of Mexico. Mexico allowed the Americans to come in, with the expectation that they would become Mexican. Why did they want them to come in? Because Chihuahua is just a desert with no railroad. How can you secure that space unless you have people in it who are going to be loyal to your government? But instead the Americans decided they wanted to break away. They were doing something illegal by doing that. I think it’s really interesting how — and it’s probably just a pragmatic philosophy of Anglo-American culture — history is not important. If you actually believed that the land had a history, could you go and take the land away from people?

Victor Estrada, The Spirit of the Living and the Dead and Cotton Candy / Posada, 2017. Oil on panel. 48 x 60 inches.

NH: It’s only when history is convenient to whatever ideology that you’d look back… .

VE: This whole thing about the Confederate monuments, which were put up 30 years or more after the Civil War, and were meant to subjugate African-Americans. But we don’t want to acknowledge where all the hangings took place.

NH: It’s interesting in an aesthetic sense — putting up equestrian statues of “heroes” in an official aesthetic obscures other histories and narratives.

VE: I do think that there’s a particular anxiety in the United States that has to do with this notion of displacement. Anglos came, displaced native peoples, and yet they claim this was a place given to them by God, so there was always a feeling of threat. With African-Americans, there was always this threat, so [Anglos] had to maintain slavery. The Mexican-American War, the internment of Japanese people, etc — all of these things have never really been completely resolved. Slavery is a kind of original sin — it was encoded in the Constitution. With whites’ understanding that they will no longer be the majority population by 2050, now they are trying to reclaim something, this thing called white identity, whatever that is and whatever that means. And I think that impulse is not necessarily a negative impulse, but it creates a lot more conflict. As all stories do. There’s no objective truth.

NH: But that’s what art does too.

VE: It makes up stuff. Yeah, [with art] you try to get to some sort of truth in experience in some way. At least that’s what I’m trying to do.

2 comments

I am so excited to learn about Victor Estrada’s work. I am going to start showing it to students in my classes.

I’m very proud of you Victor, I always knew you where interesting and smart. Some day every one will understand what you always stood for, and regret that they didn’t understand you. Well good luck and don’t stop doing what you believe in. I love you Victor, and may God bless you always. Always Lupe.