The Metropolitan Museum of Art has more than two million works in its collection. The Brooklyn Museum has one and half million pieces. The Louvre boasts 380,000, nearly one-tenth of which are on display at any given time. The Blanton, here in Austin? Nearly 18,000 artworks.

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art clocks in at 34,678 works of art. Jay Mollica, SFMOMA’s creative technologist, gives us the vivid statistic that “If you were to walk past each artwork currently on view, you would walk almost seven miles. To show the museum’s entire collection at once would require the construction of another seventeen SFMOMAs and you would need to walk the equivalent of 121.3 miles to see each piece.” It was the vastness of even this “smaller” museum collection that prompted the creation of “Send Me SFMOMA,” a phone number that anyone can text, and then receive an image of a work from the collection. So even though you may not be able stroll into the galleries of SFMOMA right now, you can poke around the museum’s works that are tucked away in storage by sending a message to 572-51. Your requests can take the form of a theme, keyword, or color, as long as they start with the command “Send me… .” Users promptly receive an image, along with the artist’s name, title, and year the work was made.

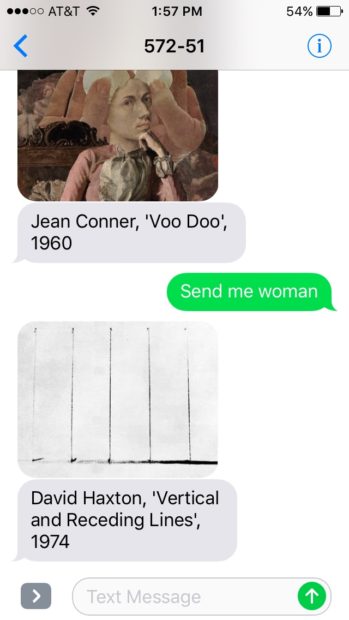

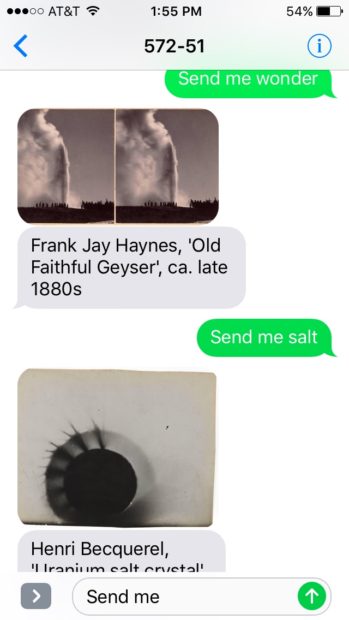

When I started down this texting rabbit hole, it felt like an exercise in poetics. How would SFMOMA’s computer program respond to a demand for something abstract, like “open” or “wonder”? My request for sadness was answered with a photograph of a young man with rosy cheeks yet to grow facial hair, in riding chaps, a cowboy hat, and neckerchief. His expression is entirely still –– not a mask, but there’s nothing that evokes sadness per se. Yet the fact that this photograph was tagged as such prompts one to wonder what narrative lay beneath the surface of his composure. When I asked for “woman,” I received the spectacular abstraction of David Haxton’s Vertical and Receding Lines and felt surprise and relief that I hadn’t received an explicit interpretation.

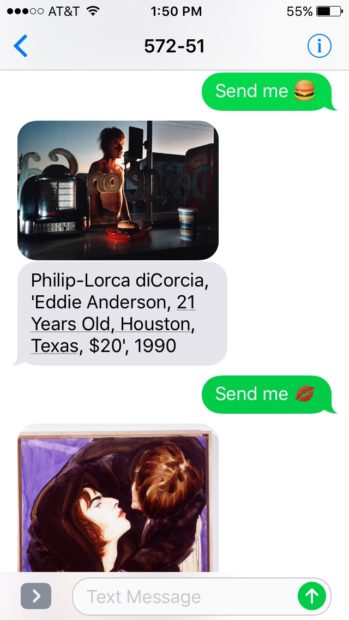

There was the fun, too, of playing with the less sophisticated slant of the app by sending an emoji. My cheeseburger emoji yielded Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s classic photograph, Eddie Anderson, 21 Years Old, Houston, Texas, $20, that shows a young shirtless man (whose body is implied to be for sale) exquisitely lit outside the painted window of a diner, a cheeseburger in a red plastic basket on the counter in the foreground. It’s a stunning image, and the cheeseburger seems inconsequential in this narrative of the boy engaged in sex work, but there it is: my silly prodding created an opportunity for a profound and provocative response from the museum.

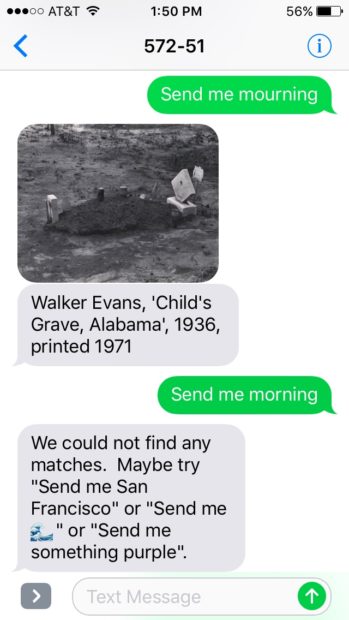

Of course, some requests stump the API software. I texted “Send me mourning” and immediately got a photograph of a child’s grave by Walker Evans. I liked the pun angle, and requested “morning” immediately after. I got a polite response that said it couldn’t find any matches. “Transcendence” also seemed to baffle the program. I have a certain fascination with probing the limits of technology. I attempted to get work by particular artists sent to me, and instead got images that included the first name of the person I had requested. Over the course of five days, the work I received ranged in years from 1856 to 2012, and the artists included many who are familiar (Diego Rivera, Ansel Adams, Richard Misrach) as well as many I had never encountered (Jean Conner, Jona Frank, Apichatopong Weerasethakul). Send Me SFMOMA’s platform plumbs the depths of the collection, giving us unprecedented access to something that’s bigger than we can really sense. Many museums are creating digital catalogues of their collections, but this creative extension of that idea allows us to meander, to explore the catalogue by pulling a phone from our pocket. It’s a way to excavate art that hasn’t seen the light of day in decades, and pull lesser-known artists’ work into one’s awareness, and in a personal way. It’s about discovery, like turning over stones to find small marvels where you least expect it.

After a while, I felt demanding with all my “send me this” and “send me that”s, and wondered how many requests the program was fielding. (The answer: Millions. It broke for a spell after Neil Patrick Harris tweeted about it). The rub with the Send Me SFMOMA program is that users are limited to the frame of language, to the ability to name something. But I can’t name the ineffable feeling I got the first time I visited Walter de Maria’s Earth Room in New York — one that prompted me to return to the space another three days in a row. With the museum’s app, the potency of an in-person experience is ironed out by the glow of my phone screen. Art can come alive when words won’t suffice. It steps in when we are in what Frederic Jameson called “the prison-house of language.” Francis Bacon said, “The job of the artist is always to deepen the mystery,” and in many ways the most enchanting part of Send Me SFMOMA is in the moments when the computer program and our human demands don’t align. Beauty arises from the slippage between a word and a corresponding image. Intentional or not, that’s really what makes Mollica’s bot such a hit.

1 comment

We tried anything with woman artist and all variations and only got men, in every form.