It’s not the elusive Marfa Lights or the filming of Edna Ferber’s Giant or, for that matter, its stalwart ranching community, for which the town of Marfa, Texas, is best known. Even outside of the international art community, Marfa means Donald Judd, Judd’s art projects and the Chinati Foundation, the world’s largest collection of artworks permanently installed at sites devoted exclusively to their display.

With 2011 marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of Chinati’s opening to the public, two new books provide valuable background information on Judd’s work, his influence on how art is displayed and his impact on the town. In very different ways, each articulates most of the ideas and actions that brought Chinati to international attention and transformed Marfa from an isolated outpost to a cultural Mecca.

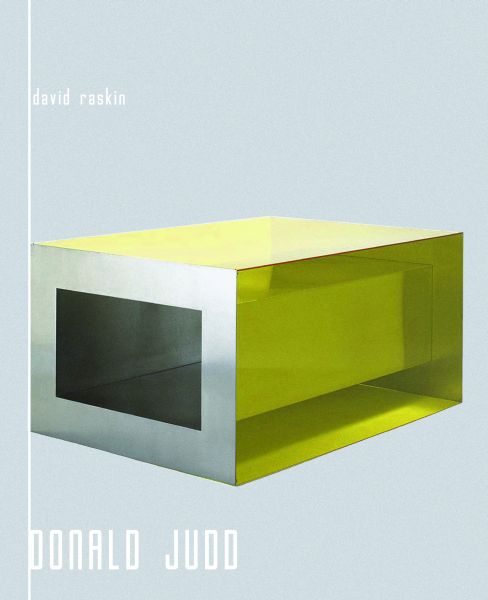

David Raskin’s Donald Judd reaches back to Judd’s years in New York and to his work as an artist, as well as art critic and social activist. Raskin is chair of the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and he writes for readers seeking intellectual engagement. If he operates at a scholarly remove, Raskin nonetheless does a terrific job of getting into Judd’s head and conveying the artist’s feelings and motives.

Raskin argues that Judd saw no gap between art and life: the two were interconnected. Judd demanded that his works be experienced as material objects, occupying specific spaces in the material world. As such, Raskin seems to indicate that Judd’s willfulness stemmed as much from his heart as it did his mind. His Judd remains intimidating, even maddening, but Raskin successfully renders both the artist and his work as more sympathetic, humane and interesting than the reputations of either have allowed.

Raskin also devotes about half of his book to Judd’s community activism, an aspect of Judd’s life that seldom is discussed. With his ex-wife, Julie Finch Judd, Judd tried organizing his New York neighborhood into a township that could exercise more influence over its own political destiny. When New York proved impervious to grassroots initiatives, Judd relocated to Southwest Texas. For Raskin, Judd’s work in and with Marfa might be described as something of a social studies project, even though Judd’s vision of Chinati was for an optimal display of the art he believed was important. Overall, Judd saw correlations between a civic society that operates humanely, and art installations that inspire members of society to become more aware of their humanity—with both existing in harmony with the natural world.

In the end, however, Raskin suggests that Judd’s impact on Marfa is one of unintended consequences: Judd had seen Chinati and Marfa as his refuge from an increasingly corrupt relationship between capitalism and centralized government, consumer culture and the dumbing down of American society. In contrast, Raskin describes Marfa today in terms of good coffee, vegetarian restaurants, expensive houses and bumper stickers that bear the legend: “WWDJD?” (‘What Would Donald Judd Do?”).

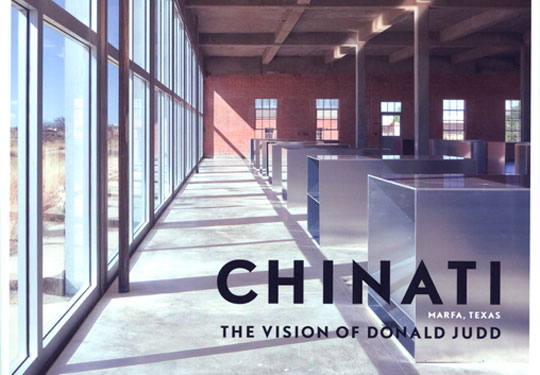

The second book, Chinati: the vision of Donald Judd, is edited and largely written by Marianne Stockebrand, director of The Chinati Foundation from Judd’s death in 1994 through early 2011. The first comprehensive monograph on the Chinati collection, it features thoughtful essays and scores of gorgeous new installation photographs. Documentary words and images also address sites that are owned and administered by Judd Foundation—evolved from the artist’s estate and steered by his children, Rainer Judd and Flavin Judd—including the building at 101 Spring Street in New York, as well as Judd’s ranches and the buildings he bought in downtown Marfa for his personal use.

The second book, Chinati: the vision of Donald Judd, is edited and largely written by Marianne Stockebrand, director of The Chinati Foundation from Judd’s death in 1994 through early 2011. The first comprehensive monograph on the Chinati collection, it features thoughtful essays and scores of gorgeous new installation photographs. Documentary words and images also address sites that are owned and administered by Judd Foundation—evolved from the artist’s estate and steered by his children, Rainer Judd and Flavin Judd—including the building at 101 Spring Street in New York, as well as Judd’s ranches and the buildings he bought in downtown Marfa for his personal use.

Consistent with the overall material clarity of Judd’s work and Chinati installations, Stockebrand’s book itself is designed according to prototypes that may seem old school but ensure optimum legibility. It is a document and a guide, built around Stockebrand’s intensely engaged, often lyrical and always clear perspective about what Judd wanted to accomplish with Chinati. It communicates how Judd’s dreams for Chinati have been realized, along with the revitalization of Marfa.

In mild contrast to Raskin’s ultimate pessimism, Stockebrand represents Judd’s direct interventions and his indirect impact, via Chinati’s success, as having a constructive impact on both Marfa and the experience of art. Given that Stockebrand legitimately can claim much of that success for herself—it was she, for example, who negotiated and found funding for installation of Dan Flavin’s sublime untitled (Marfa project)—the book’s affirmative tone is not surprising.

But it’s not pure fluff, either. Thanks to Judd’s passion for architectural preservation and adaptive re-use, Marfa and Fort D.A. Russell have regained much of the beauty that was there all along, but had become invisible. Through his interventions, Judd allowed beauty to be visible again, by repairing and renovating structures; by installing artworks whose material and visual properties complemented their environments; by clearing land of debris and allowing it to heal. Stockebrand’s determination to fulfill Judd’s vision as completely as possible meant cultivating support through outreach. Expanded programs served and continue to serve area residents, attract more funding and bring in visitors—about ten thousand annually—whose spending helps offset revenues that are lost every year, due to the tax-exempt status of the Chinati and Judd foundations and local non-profit organizations.

Marfa’s present robust state of affairs was not always certain. There was no evident up-side when, in the early 1980s, Judd started buying property and closing it to the public and/or removing it from the tax rolls. Then, in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001, flocks of frightened urbanites moved to Marfa, creating a real estate bubble and fanning already-existing concerns that Marfa would head the way of Santa Fe.

Robert Halpern, editor and publisher of the local weekly newspaper, the Big Bend Sentinel, says that, although Judd laid the groundwork that transformed Marfa from a ranch town into a cultural Mecca, Marfa remains true to itself. What makes town and art unique is the desert, the landscape that Halpern, a Marfa native, calls “ground zero”.

Looking ahead, there is no telling if Marfa, Chinati, the other Judd properties and the desert they occupy will be further transformed, for better or worse, by art tourism or other political, economic and environmental forces. What both texts suggest, however, is that an art project on the scale Judd initiated has the power to shape the world around it in, regardless of Raskin’s ultimate pessimism, a positive way.

Janet Stiles Tyson, independent art historian

Spring Lake, Michigan