Vernon Fisher started off his art career as an abstract painter, but by the mid-1970s that line of inquiry came to a screeching halt. He began making small books instead. The books evolved into multi-media narrative paintings in which a short story was laid out in large type over a seemingly unrelated, large-scale black-and-white photographic image.

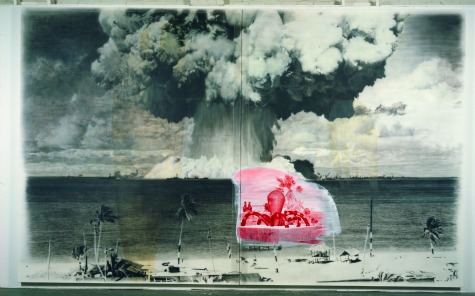

A feeling of disconnection pervades Fisher’s work; the relationships between text and image or object are never obvious or clear. Fisher’s work encompasses drawing, painting, sculpture, found objects and photographs, silk screens and occasionally even cryptic audio tracks. The iconography often depicts the familiar; “things that we know” as Fisher explains, simultaneously bouncing between maps, globes and measuring devices to vintage cartoon characters like Nancy, Aunt Fritzi and Mickey Mouse, to textbook images of Bikini Atoll.

One of his best-known series is the large-scale blackboards which began in 1980 and have evolved into visual puzzle vehicles, full of smudges, scribbles and erasures to emphasize “the tentative and fluid quality of the mind at work.” His most recent series consists of large battlefield map paintings, incongruously warped in classic deadpan Fisher style.

A voracious reader, Fisher often describes his art from the standpoint of a writer. Despite the dark and foreboding nature of much of his work, Fisher never abandons his droll wit. His short-lived Zombie series from the late 1990s included three-dimensional fake houseflies at rest on canvases of impasto abstractions of fields of color.

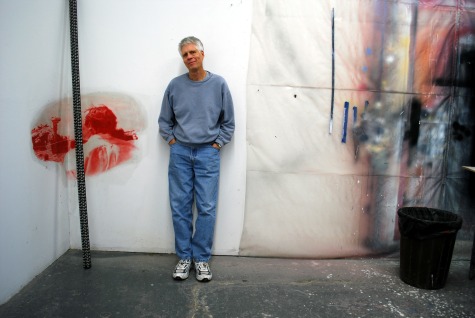

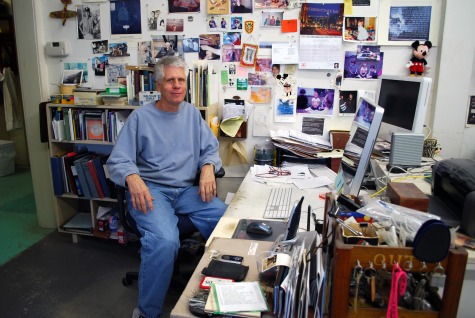

An adept technician, the artist is personally as enigmatic as his art. Fisher is among the most erudite, intellectual artists working today, yet is an avid sports fan and a hardcore Dallas Cowboys devotee who finds time to regularly tee off with a group of like-minded art folks at public golf courses in his hometown of Fort Worth.

For more than thirty years, Fisher taught painting at the college level, most of it at the University of North Texas in Denton where he is Regents Professor of Art Emertius. Through his highly disciplined work ethic and fertile imagination, he has created an overwhelmingly large body of work that has been shown in over eighty one-person exhibitions throughout the world. Fisher has been included in two Whitney Biennials and in 1995, he was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship.

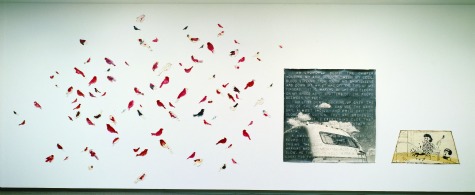

This fall, the University of Texas Press published a 244-page career monograph of his career, Vernon Fisher. In October, the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth opened Vernon Fisher: K-Mart Conceptualism, a career retrospective which spotlights his work over the last thirty years. It’s been a homecoming of sorts, as Fisher is reunited with some of his early work for the first time in twenty years. We walked through the Modern’s galleries together to look at the show, starting with 84 Sparrows, a fitting preamble to the following thirty years of his career.

Vernon Fisher, 84 Sparrows, 1979, Acrylic, graphite, and laminated paper, 69 x 176 inches, Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Courtesy UT Press

Christina Patoski: Why did you abandon being an abstract painter?

Vernon Fisher: It just wasn’t a big enough container. So, I started making books, little one-of-a-kind books. Then, out of the books came the narrative paintings.

CP: Your degree is in English.

VF: Yes.

CP: So, you’ve always been a reader.

VF: Yeah.

CP: And a writer.

VF: To some degree. I had to learn to write. I think I got better at it as I went along. The later stories are a little bit more sophisticated.

CP: Is 84 Sparrows one of the earliest?

VF: No, the earliest one was 1975. 84 Sparrows is from 1979, so I had four years under my belt before I got to it. If you notice, this piece has got three parts lined up from left to right. It was among the first pieces to string the components along the wall like a sentence⎯a subject, predicate kind of thing. This understanding of the structure occurred to me much later, of course. It was pretty much unconscious at the time.

CP: So, the narrative paintings started out smaller?

VF: No, they started out big. The first one I did was five feet square. Then, the next one I did was like eight feet square. I did large ones for the first several years. Technically, I was limited by the size of the letters that I could get.

CP: You literally hand set them?

VF: Yes, and then sanded them through.

CP: That’s how you did all of them, you hand sanded them out?

VF: Until recently. Now I use a vinyl cutter.

CP: You still had to put the letters up.

VF: Basically you set type.

CP: Big type.

VF: Big type. And then you put the painting on top of it and sand it.

CP: Or in this case the photograph.

VF: This is a drawing.

CP: This is a drawing?

VF: Yeah.

CP: Pretty labor intensive.

VF: Not so much. It depends on how complicated the photograph is. Certain photographs are harder than others. It’s something Ed Blackburn and I would talk about at times. The more distressed the photograph is, the easier it is to paint because the grays have collapsed into black. A lot of detail is lost. Plus, I like that murky feel. It feels important to me.

CP: But, these look like three separate pieces.

VF: It’s a piece where all the components are very different from one another, but they go together and your job is to figure it out.

CP: Or make your own connections.

VF: The connections are relatively available if you spend time with it.

CP: Kind of like what John Cage did.

VF: Yes. Cage counted on people’s expectations about music to be part of his pieces. 4’ 33” is a good example. It enlarges your idea of what constitutes music. Very Zen.

In my case, I count on expectations we have about a literary text. In both cases, you have to re-adjust expectations about what you’re going to get or how you’re going to go about getting it, but there is something to get at the end. An unexpected pay-off.

A text has its own reality. When you read a text, you can’t look at anything else. You’re reading the text. You’re mentally picturing the things that the text is referring to. You’re not in the space with the painting because text space is just somewhere else.

CP: A different part of the brain?

VF: I don’t know. I do know that when you read a text, you’re taken out of the space you’re in. I wrote a very vivid story about floating down the Ganges River. You feel the flow of water, see the stars wheeling overhead, feel fish sucking on the tips of his fingers. You come to the end of the story and find yourself suddenly staring at a piece of plywood. What interests me is having those two kinds of experiences available in the same piece.

Once you’ve read the text, it’s inevitable that you’re going to make certain connections with the other components. That’s kind of the way it works.

Vernon Fisher, Stick-Chart Navigation, 1983, acrylic, oil, and shells on laminated paper, wood, and metal, 94 x 272-1/2 inches, Gift of the Women's Committee of the Corcoran Gallery of Art

CP: You started expanding the narratives to include sculptural pieces with found objects, like Stickchart Navigation.

VF: Yeah, an object is pretty much as different as you can get from a text. Objects are concrete and present. Texts are, I don’t know, ephemeral in comparison.

CP: Are some of the narratives actually events that have happened to you?

VF: No, of course not. People who write stories, what do you think they’re doing? They make up stories, it’s fiction.

CP: You’ve created your own little world; it’s like each work is its own little universe.

VF: Yeah, but then all the universes share certain commonalities. There’s a preponderance, in the narrative things at least, of people in situations where things aren’t adding up for them. Like in Stickchart Navigation, a girl trying to figure out where her boyfriend goes when he disappears for weeks at a time.

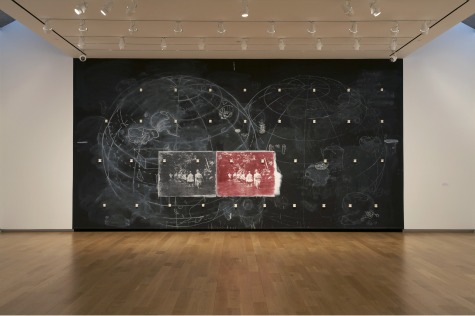

Vernon Fisher, Complementary Pairs, 1987, Acrylic and chalk on latex with plaster teeth casts, 12 x 25 feet, Collection of Dr. and Mrs. Eric H. Scheffey

CP: Complementary Pairs is painted directly on the wall. You said this is the seventh time you’ve mounted it and that it’s always different sizes.

VF: Yeah, you have to adapt it to the space. The first time was at Hiram Butler Gallery in the early 1980s. Then in the mid-career survey it was installed at four museums. That makes five. Then it was installed for a collector. The installation at the Modern is the seventh incarnation.

CP: How long did it take you to do this one?

VF: It took a week on site, but there was a lot of preliminary work. Some of the original technology had almost completely disappeared and I had to improvise workarounds.

Vernon Fisher, Private Africa, 1995, Oil on blackboard slating on wood, 92 ½ x 93 ½ x 4 inches, Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Courtesy UT Press

CP: When did the blackboards start?

VF: The first one was made in 1979. It was a component of a multi-part narrative piece. I used them a lot as components early on.

CP: There is still some narrative in these paintings, but it’s visual narrative.

VF: Right. The essential elements of a story are always present. It’s situational in some way. You have the suggestion that there are things to be added up.

CP: I remember at your own opening a woman asked you, “what does this mean?” Do you intend for it to mean anything?

VF: Of course. But, meaning in art is not a bottom line. It’s more like a constellation of feelings. But, because these paintings present themselves as something to be added up, expectations can veer toward that bottom line kind of approach. But, you know, people get it. A guy approached me at the opening. He was very excited. He said, “I really love this. I get it, then I don’t get it, I get it, then I don’t get it.” He was enjoying the process of interpretation.

Vernon Fisher, Bikini, 1987, Acrylic on canvas, 11 ½ x 18 ½ feet, Collection of the Krannert Art Museum, Courtesy UT Press

CP: Where do you put yourself in the pantheon of artists, as in post modernist or post—post-modernist?

VF: I don’t put myself anywhere because that’s not my job. Other people get paid to do that, know what I mean?

CP: You started out as an abstract painter.

VF: Yeah, as a modernist. There’s a question as to whether modernism actually disappeared. It depends on how you define it. But, there’s clearly been a revision of emphasis. There was a moment up to the middle of the 20th century where you could still believe that you were saying something about reality. Somebody like Mondrian could truly believe he was capturing some essential nature of the universe. I don’t think anybody believes that anymore. So, basically what you’re left with are questions. Everything is suspect, so questions themselves become the subject matter. Which is why a lot of my stories are about people who are lost, or trying to read a map, or trying to figure things out and not figuring them out, being in a situation where the rules aren’t clear.

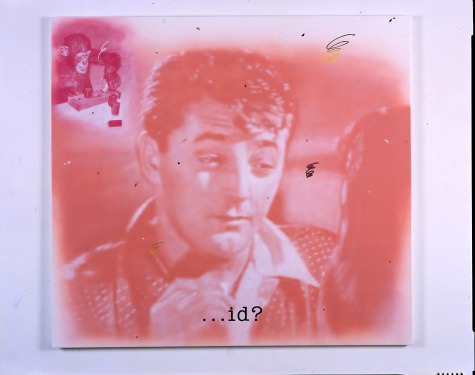

Vernon Fisher, Three-way Conversation, 2000, Acrylic on canvas, 72 x 93 inches, Courtesy of Dunn and Brown Contemporary, Dallas, Texas

CP: You and your wife Julie (artist Julie Bozzi) watch a fair amount of television and old movies.

VF: Now you’re talking about yourself, Christina, watching all the old movies. I like to watch old movies too, but you can’t get Julie to watch an old movie.

CP: You use stills from some of them.

VF: I do. It’s a good place to find images to paint.

CP: Because they’re archetypal?

VF: No, because you can find murky. Mainly in film noir. Like Three-Way Conversation, it’s from Angel Face, you know the movie with Robert Mitchum and Jean Simmons. There’s another one that’s not in the show called American Tragedy which is reproduced in the monograph. It was taken from A Place in the Sun which is based on the Theodore Dreiser novel An American Tragedy. There it is, boat out in the lake, murky background⎯foreground, Shelley Winters and Montgomery Clift toppling into the water.

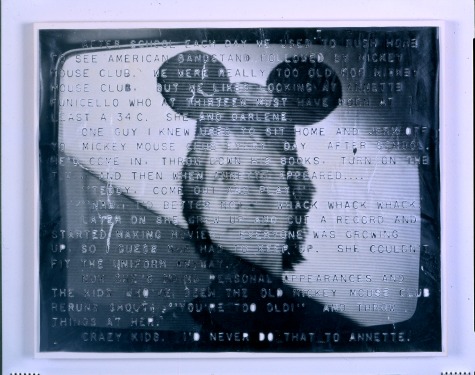

Vernon Fisher, Annette, 1977, Photograph on laminated paper, 22 x 27 inches, Collection of Bob and Ann Myers

CP: When did Mickey Mouse first show up in your work?

VF: I think it was Annette, probably in 1977.

CP: Were you too old for Mickey Mouse?

VF: Yeah, but when I was a kid I watched Mickey Mouse Club on TV.

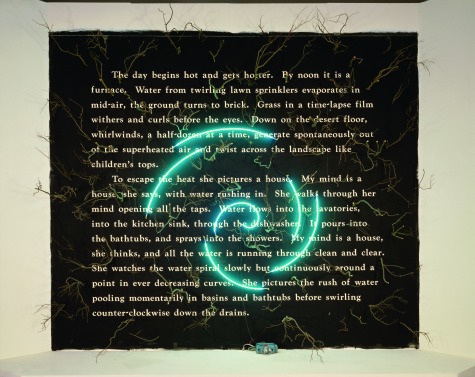

Vernon Fisher, The Coriolis Effect, 1987, Green neon, text on wall with sculptural elements, 204 x 180 x 60 inches, Installation at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Courtesy UT Press

CP: One thing I’ve always found interesting about you is you’re such a creature of habit.

VF: It’s called O.C.D.

CP: I don’t think of you as having O.C.D. Do you think you have O.C.D.?

VF: Oh yeah. There’s no doubt. Rituals employed simply to control and reduce stress.

CP: For years, you went to Luby’s every day for lunch and you’d order the same thing.

VF: No, I went to Luby’s every day, but I didn’t always order the same thing.

CP: Since Luby’s has closed, where are you going now?

VF: There’s about three or four places I go to. I still go at 11 to beat the crowd because I don’t like to wait in line.

CP: My point is that you lead a very disciplined private life, but when you look at your work one could easily make the assumption that “this guy’s probably really wild.” Maybe internally you are.

VF: The world of imagination is quite different from the world one inhabits. Let’s face it, all writers do is sit at a computer. They don’t live the lives they write about.

![]()

Christina Patoski is a journalist and photographer who lives in Fort Worth. A former NPR reporter, she has been published in Newsweek Magazine, The New York Times, Life Magazine, and USA Today. Her photographs have been exhibited in museums and galleries throughout the United States, including the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History. She received a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship grant for her video and performance art which was shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art,the Walker Art Center and the SanFranciscoMuseum of Modern Art.

1 comment

Wonderful interview! Thanks so much for this link!!