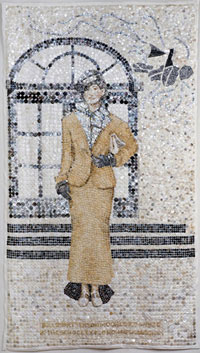

Billie Patterson Moore died in the...school explosion in New London TX,...95.25 x 54 inches, mother-of-pearl...and bone buttons on linen, 2005-07

In an earlier era, Marilyn Lanfear might have contented herself with keeping scrapbooks, painting watercolors, making quilts and telling her stories after serving a big family meal. But in her late 40s, she earned an MFA from the University of Texas at San Antonio and studied art theory, especially minimalism and conceptualism. Then she moved to New York and spent five years working in a gallery, absorbing the city’s multifaceted art scene.

Though she began as an amateur realistic watercolor painter devoted to raising her four children, she is trained as a painter and printmaker. But she’s become a master at manipulating multiple materials, which she uses to construct her conceptual installations and sculptures based on her family’s oral history. While her work is rooted in her childhood and life in Texas, Lanfear transforms traditional feminine craft through techniques most often associated with men’s trades, such as welding lead dresses and carving curtains in wood.

“If they don’t like my ideas, then I give them craft,” Lanfear says. “I’m not trained as a sculptor, but I’ve always been able to find someone to show me how to do things, like solder or carve limestone. I’m always careful to provide details of what life used to be like. I think some sense of what the bygone eras looked and felt like are being lost. While living in New York, I used to talk about my family, telling my stories. And one day, one of my sophisticated New York friends said, ‘I wish I had stories to tell like you do.’ That made me realize that what was common and ordinary to me was exotic to some people; that I really did have interesting stories to tell.”

Named the Artist of the Year by the San Antonio Art League, Lanfear is the subject of the one-woman retrospective Marilyn Lanfear: Storyteller, on view at the Art League Museum in the King William Historic District.

“I am a visual storyteller who translates personal family stories into a common mythology of family generational connections,” she says in her artist’s statement. “I use whatever is needed to tell my story. Subtle elements like the pattern of wallpaper, the use of traditional milk paint, or folded clothes rendered in stone, load the images with irony and symbolism not repeated in the oral tradition. Narrative is the moving force of my visual language with the history of my Texas family as the core.”

Three large tapestry-like portraits made with thousands of antique buttons depicting the three wives of her Uncle Clarence form the centerpiece of her retrospective. Beginning as a project at the newly-rechristened Southwest School of Art, Lanfear spent two-and-a-half years working on the triptych of larger-than-lifesize portraits, carefully selecting the buttons to provide the illusion of shading in the distinctive dresses worn by the women in three eras: the Great Depression, World War II and the 1950s.

“I stood up on a stool over the portraits, which were flat, so I could pick out the buttons and get the shading right,” she recalls. “But one day, I stepped back and fell off the stool, breaking my wrist. So it took me a long time, and I couldn’t have done it without the help of assistants.”

Lanfear used mother-of-pearl buttons in all three portraits, but her Aunt Billie, pictured in 1937, wears a long, form-fitting, ankle-length dress made with rare antique bone buttons, which have a yellow, buttery look. Aunt Billie stands on the steps of the school in New London, Texas, which was destroyed in a gas explosion that claimed nearly 300 lives, most of them children. You can see whirls of motion and parts of the exploding building in the upper right hand corner of the portrait.

Grandmother's Library Table With Photographs, 42 x 65 x 18 inches, irregular ink, rag paper, vintage frames, antique table, 2001

“My Uncle Clarence was working in the big East Texas oilfield and the boomtown of New London had built a new school, which was the pride of the town,” Lanfear says. “They built it for $1 million, which was a lot of money in the 1930s. But they decided to use ‘green gas,’ which they didn’t have a market for, to heat the school. One day the janitor plugged in his sander and a spark set off the gas, completely leveling the school. My Aunt Billie had gone by to see her sister who worked as a secretary. She was standing on the front steps when the school blew up. Her sister was also killed in the blast. Uncle Clarence rushed to the scene like everybody else in town, but didn’t know Auntie Billie and her sister had died.”

During World War II, Uncle Clarence married “Aunt Gerry,” though Lanfear says she doesn’t have much information about the short-lived relationship. With a military jacket draped around her shoulders, Aunt Gerry, wearing a summery dress, stands at the edge of the woods, similar to the area around Paris, Texas, where the couple had a house during the war. For an authentic look, Lanfear used buttons from a sergeant’s uniform to make the jacket. In her hand, Aunt Gerry holds a “Dear John” letter.

“I don’t know if Uncle Clarence got a Dear John letter while he was serving in Italy, but the marriage didn’t last much longer than the war,” Lanfear says. “The little vignettes in the upper corners come from Renaissance paintings, which would have a road or castle or scene from a story. It helps to give more context for the images.”

In the early 1950s, Uncle Clarence married “Aunt Bea,” and they remained together for 41 years. They had three children, who are pictured in the portrait with Aunt Bea wearing high heels and a ‘50s-style dress with broad white lapels and a full skirt made up of buttons in various shades of black and gray. After the family moved to Louisiana, Uncle Clarence went to work for the Humble Oil Company and was among the first men to work on the off-shore oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. A boat, resembling a tugboat, is in the upper right-hand corner of Lanfear’s portrait, along with a platform oil rig in the distance.

Pedestal & Bride (M For Michelle), 102 x 38 x 38 inches...irregular artist made paper, antique column, 1997

“I wasn’t sure what the boat was supposed to look like until I met a man at a party who said he had been among the earliest workers with my Uncle Clarence,” Lanfear says. “He said they used any kind of boat they could find and retrofitted them for use in the Gulf. To me, these three portraits span the history of oil in Texas during the 20th century.”

Lanfear also transforms ladies’ fashions into unusual materials, which often allude to feminine toughness despite their fragile appearance. She carved several hats from her Aunt Mabel’s collection in limestone, which are displayed on a table covered with a handmade paper tablecloth. The hats almost look like they could be helmets. Lanfear calls the rock hats “Headstones.”

In another series based on women’s headpieces, she uses lead to reproduce the frilly ornamentation, which are displayed on wood stands based on pedestals she saw at New York’s Asia Society used to display samurai helmets.

She’s also used lead to create a series of aprons that pay tribute to women she admires called Woman Shapes a House. Spread out, framed and mounted under glass, the lead aprons resemble armor. She also makes lead dresses based on young girls’ dresses, which she displays on antique children’s chairs.

“My brother gave me some lead to work with one time, and I spent a long time thinking about what I could use it for, and then decided to make dresses with it,” Lanfear says. “The aprons are made with lead stickers that protect a dentist’s X-ray film. The pieces are sewn with silver thread and can function like armor, which I think represents a source of a woman’s strength. I have to be careful working with the lead and I always wear gloves and a mask as well as getting my blood checked regularly for lead content. But I haven’t had any problems with it.”

Most of the stories Lanfear knows are told from a female point of view, but since this history of women isn’t much preserved in the state except as oral history, Lanfear’s use of lasting materials is partly intended to make sure the stories last forever.

A bride’s dress made with white handmade paper hovers like a ghost over a Greek column in Pedestal & Bride, a wry take on the idea of women being idealized and “placed on pedestals." One of Lanfear’s funniest yet respectful pieces, Mother’s Chair, explores a similar idea. It’s a reproduction of her mother’s overstuffed, green-patterned upholstered chair made entirely with handmade paper, which is placed on a high pedestal like a throne. As part of the piece, Lanfear hides a coin under the cushion.

“I’ve lost a lot of coins over the years of showing this piece,” she says. “People read the label and see ‘coins’ on the material list and dig them out. I always use a coin from the period, so this time it’s a buffalo nickel.”

Among her most nostalgic pieces is an antique side table covered with family photos, which Lanfear has carefully re-created by drawing them in ink and placing them in old-fashioned swing frames. But the images have a universal appeal because Lanfear leaves the faces blank so viewers mentally can fill in the visages of their loved ones.

As a woman born and bred in Texas, Lanfear makes art that is overt in its femininity but covert in its feminism. There’s nothing especially political about her work; in fact, it’s more humorous than not. But memory is a continuous theme—how it is preserved, and what is worth remembering and why.

As the late artist Henry Rayburn said about Lanfear, “She’s like a colorful aunt, telling her stories about the family. But it could be your family too. Marilyn’s work does what anyone’s grandmother’s attic would do. It draws from us memories of family characters long gone and oral histories passed down through generations.”

Marilyn Lanfear: Storyteller

San Antonio Art League Museum

September 12 – October 23, 2010

![]()

Dan R. Goddard is

a writer living in San Antonio.