If lost in Istanbul, you should follow the city’s spine to find your way. That keeps you from climbing back the steep inclines when you take a wrong turn. If that fails, you may head to the water and walk around the chanting mosques, the sound of the city exhaling. By the sea, by the unconscious, I feel at home. "There is no city without sea." It’s a simple choice, left or right, no matter how long the walk you feel assured. On top, I feel the pressure of being lost, cab drivers egging me into a ride back home. They seem to say, be bourgeois, pay to go home.

But I stopped being a criminal at age twenty-eight. "A bourgeois is a criminal, a criminal is a bourgeois," Bertolt Brecht is being abundantly quoted at the Istanbul Biennial. Its "theme" is Brecht’s "What Keeps Mankind Alive?" This biennial has in past editions claimed political engagement and non-Western focus. In 2009 only "28%" of the artists are Western. And this edition of the biennial is definitely political. "A choice between brutality and socialism," shout the performers on stage during the opening ceremony at the sitting Minister of Culture. Off stage, off the program, protesters blare air horns. They feel the show aids the establishment. Yes, political is a fuzzy term. All art might be political since it seeks to challenge existing rules or it gives voice to that not said. And political art is arguably doomed to be politically inconsequential and even counter-active.

The roundtables and lectures of the biennial were on İstiklal Caddesi, the main thoroughfare through center Istanbul, the city’s spine. So were the real political protests, with red and black flags and chic yellow Che Guevara banners. The intellectuals sheltered in soliloquy to a mostly Western audience in hot buildings. The protesters also relied on language but under open skies and under the eye of heavily shielded and not so heavily armed police. The art was not at the city’s center but mostly by the sea. Showing what cannot be said, paraphrasing Wittgenstein. Among the myriad of political statements by the curators, the Croatian WHW1 collective of four women, I found the following most subversive: "Was it not somehow possible, we asked ourselves, to give the public some form of ‘agency,’ making choices that would boost their capacity for action. […] The proof of the pudding lies in the eating."

The Istanbul Biennial is indeed successful in giving the audience a full range of political statements. From language driven single-shot-to-the-throat statements to ambiguous and richly layered art. You may decide what works for you. Most visitors, particularly those non-Western, may find the exercise rather challenging. I found the effort illuminating despite or because the three hours of sleep nightly-they know how to party in Istanbul.

Let’s be specific. This is the artwork you would see entering the main Biennial venue, named Antrepo No.3. A former warehouse at the Salipazari Harbor on the Bosporus facing the Golden Horn and the mosque-rich old center of Istanbul. A part of the world that must be in every song of those bent on geopolitical control. Remember, this is the entry hall curated by a group that clearly chose every detail meticulously.

- A set of large black photos with a few bright spots and streaks. No much visually, but politically verbose, the long accompanying texts explain these are efforts to pinpoint the surveillance satellites over Istanbul. Visible antagonism is easily defeated and assimilated.

- One of the few 3D works in the biennial, the wonderful "Qualandia 2087" by the Palestinian artist Wafa Hourani. A future projection of a refugee camp. A bright, cleansed city, people living and playing, an airport with colorful planes, an aquarium with live golden fish, a few tiny Palestinian flags here and there. No checkpoints, no bullet holes on the walls, no coffins carried by crowds, yet the work carries a punch. Who could censor this? Here the antagonism is silent, invisible, capable of inducing paranoia.

- KP Brehmer‘s stock market graph from 1976. Trans-coding and blurring.

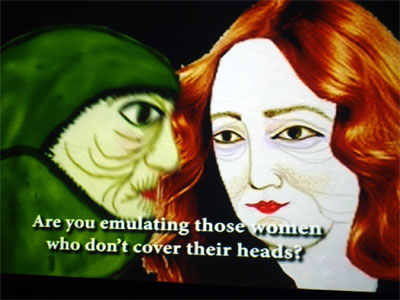

- The lactant breasts. "Fountain" by Canan Senol. Political? You bet! And without "saying anything." Senol also shines with a more verbose but also visually outstanding separate animation "Exemplary."

- A "DON’T COMPLAIN" sign by the Turkish artist Alptekin. Language-driven work whose effect lasts seconds.

- The princess and the frog drawings. "Waiting for Revolution," 1982 by Sanja Iveković. The biennial is abundant in drawing and video. Subversive media.

- Red paper wads on the floor. A report summarizing the situation of women in Turkey, also by Ivekovic now in pure language mode. The audience has been given ‘agency’ by seeing both types of work, pure ambiguous drawing and direct language-based work.

That’s the beginning of 120 "projects" by 70 artists. Some shouting political, some showing political. A lot in between. After visiting the biennial and its parties four days in a row, I found myself ignoring the overtly political and returning to the ambiguous artwork, witness for example:

The Lebanese swimmers. How do you tackle Lebanon’s political mess? Mounira Al Solh‘s brilliant approach in "The Sea is a Stereo" is to interview and document a group of swimmers, some tattooed, some shrapnel-scared, who have been hanging out for years in Beirut by, in, and through the sea, "rain, wind or war." One of the characters says the early quote, "There’s no city without sea," and they go on to be profound, funny and as human as conceivable in a war zone.

"Pomegranate" by Jumana Emil Abboud. I watched this video over and over. The inherent destructiveness of human nature made patent in the impossible effort to reconstruct a pomegranate. This work should be a good model for redundant art making. I want to put together a chicken.

"Portrait. 50 Years of a Woman" by Hans-Peter Feldmann. A profound political statement, re-appropriating time and personal history by ordering photos from a woman’s life not chronologically but otherwise.

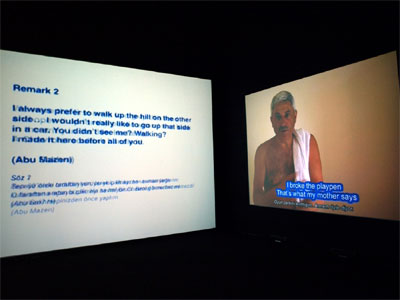

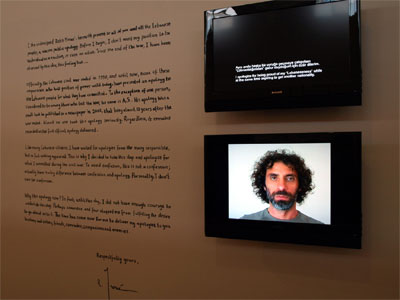

Rabih Mroue "I, the Undersigned." Apologies, not confessions or requests for forgiveness as the speaker clarifies. Some ironic, "I apologize for shooting at the sky when Brazil beat Germany." Some redundant. The text screen and the portrait have different length so they are never in synch. Plenty of nuances in this work. Good video art.

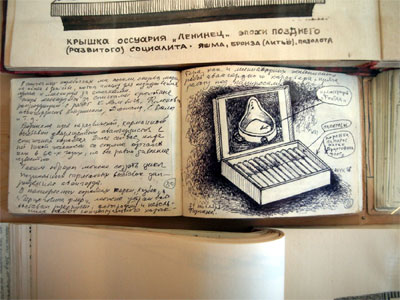

If there is good video, there is also an abundance of telling drawing in this biennial. Vyacheslav Akhunov‘s notebooks 1977-87 shine in the Tobacco Warehouse where other good Russian works are installed. Anyone into ideation drawing, memorize this man’s name – okay at least his last name.

Inci Furni‘s drawings "Spirit" make a much engaging installation and display the full range of political engagement within just one artist’s project. See the close-up. Signifiers abound in one drawing, the other is… poetic?

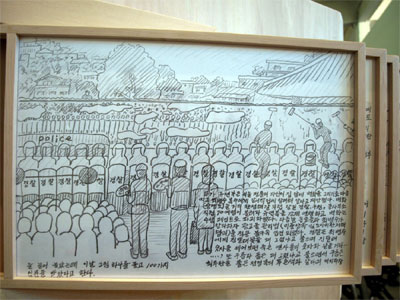

Donghwan Jo and his son Haejun Jo‘s project is a series of drawing juxtaposing personal and historical biography. The installation of the work is outstanding. This project debuted at the 2008 Gwangju Biennale. Good pick by the curators. It was sweet to find down the hall from this installation Nam June Paik‘s early modified Time magazines where he also reaffirms his history, this time with that of the media as background. Koreans are an alienated nation.

Scattered thoughts:

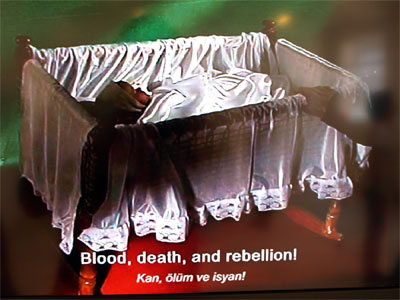

Documenta, I am headed to the first conference leading to documenta 13 (2012) and I couldn’t avoid noticing the parallels between documenta and this biennial: multiple "projects" by the selected artists, not limited to contemporary artists but to significant work, an effort to give voice to overlooked artists, even down to a book of "texts" accompanying the catalog. I mentioned these parallels to Ivet Ćurlin, one of the curators. She didn’t like to hear it. The Istanbul Biennial tries so hard not to be Western! By the way, that "28%" of Western artists inflates to 45% when you look at how many artists live and work in the West. No one said how many were educated, have lived, have worked, or are strongly influenced by the West. That 28% may be 82% after all. It was refreshing to speak to Jinoos Taghizadeh, an Iranian artist actually still at home and making politically engaged works. Newspapers with their text removed, a video of a rocking crib with a wonderful voice chanting a lullaby composed of revolutionary songs. That takes guts.

On political ineffectiveness, I am adding Nicolas Bourriaud. The "curator and theorist" who shares that tempting vein of French philosophers: if it sounds good, it must be true. I might be enchanted by Bourriad’s texts, but I was disappointed by his "debate" of those critical of relational aesthetics. A boring Sunday-morning monologue where he gave limited takes on critics, including Claire Bishop (who pointed out in 2004 the lack of "antagonism" in relational aesthetics and not only the issues of art in ‘unstable flow’ as Bourriaud put it). Even the Q&A was seriously restricted. He fumbled his way around the simplest question, "Define political outside art." He dropped plenty of great one-liners though2.

In the verbose front, "ambiguous" and "redundancy" as political approaches were common themes. Stephen Wright was quoted by the curators in text and video challenging production in contemporary capitalism and art, "the answer may be negative growth," "we have to dare to seek Exodus from the ‘society of work’," "Walking Political." Rejecting productivity could be extended to "being lazy," "paresse" in French ("Bonjour Paresse" by Corinne Maier, 2004) as subversive. Fits the above Lebanese swimmers. The art of doing nothing came up more than once at the parties. Have to justify all that drinking.

You decide what works for you as political art. Somewhere between going for the throat and heading for the sea. Yes, the blind can lead the blind.

Photos by the author

1 "What, How & for Whom (WHW) is a non-profit organization for visual culture and curators’ collective formed in 1999 and based in Zagreb, Croatia. Its members are curators Ivet Curlin, Ana Devic, Nata_a Ilic and Sabina Sabolovic, and designer and publicist Dejan Krsic"

2 "mapping the power," "making the invisible visible," "temporary autonomous zones," "we must constitute culture on the idea of fragility," "three important figures: transcoding, flickering and blurring."

Jorge Misium is an artist and part-time writer working in Europe. He has been an accidental Texas resident for about twenty years.