If we tell stories to help us make sense of the world, then right now

the world must not make much sense because we seem to need a lot of

stories. This is one explanation for the recent proliferation of

storytelling in painting, the theme explored by Blanton Museum of Art

assistant curator Kelly Baum in The Sirens’ Song at Austin’s Arthouse.

The exhibition’s title was inspired by Maurice Blanchot’s essay “The Song of the Sirens,” which Baum reads as championing “the ability of art to revoke the boundaries between the real and the imaginary.” This confusion between fact and fiction has allowed Baum to construe storytelling broadly—including personal narrative and pure fiction, as well as political allegory and current events—but the most powerful parts of The Sirens’ Song resonate with anxiety and despair, slicing through our contemporary moment with enough force to make this uneasy undercurrent the exhibition’s main attraction.

Violence dominates the smaller of Arthouse’s two main galleries, with well-chosen paintings by Seth Alverson, Joey Fauerso and Gilad Efrat. Alverson’s monumental, macabre diptych Word Has It That Everything Has Been Permitted for Quite Some Time Now describes before and after scenes from a destructive event: A bomb, or maybe even a meteor, has ripped through the home of two middle-aged men, seated on a couch, who look perfectly normal in the first panel except they have no feet. Alverson’s palette is rich, his draftsmanship, exquisite, and his imagination, truly gruesome. In the aftermath painting, one of the men’s heads has exploded, while the other is impaled with a roof beam. Nevertheless, the painting is so seductive, and the mountain scene revealed by the destruction so beautiful, it’s hard to process the implications of what is depicted — the effect is somewhere between cinematic horror and the TV news. The scale and color saturation of Word Has It… is pure Hollywood, but the deadpan senselessness of the violence left me with the same numb feeling I get from watching CNN.

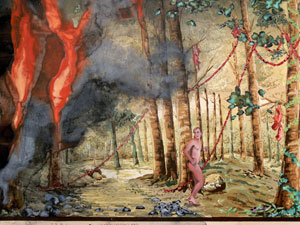

The Woods by Fauerso, a triptych of paintings on antique wallpaper, reinforces this sensation. The nude man who appears several times in a grisly landscape could easily be an allegory for ourselves as we watch global events unfold on our TV screens. He seems absolutely unaware of his surroundings even as he bathes in a spray of blood and strolls under trees festooned with meat.

Gilad Efrat...Ansaar IV...2005...Oil on linen...59 x 98 inches...Collection of Beverly and John Berry, Houston

In contrast, Efrat’s painting of a prison camp is devoid of human figures, but Ansaar IV overpowers these other, more literal representations of violence by all that it implies. The painting is based on an unpublished photograph of an Israeli detention center that was taken by a journalist, who gave the picture to Efrat for the painter to reproduce. The viewer is left to imagine what has occurred or will transpire within the empty, barbed-wire enclosure.

The politics of race and current events inform work by David McGee, William Villalongo, Philip Maysles and Trenton Doyle Hancock in the main space. McGee’s Good Government, a group of watercolors that recast the Iraq War via Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, covers an entire wall. McGee has put George Bush at the helm as Ahab, reduced the Clintons to a pair of ants and aptly portrayed Donald Rumsfeld as a toy horse. The delicacy of McGee’s watercolors belies his biting political commentary, creating a satisfying contradiction.

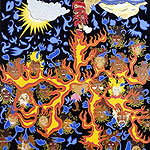

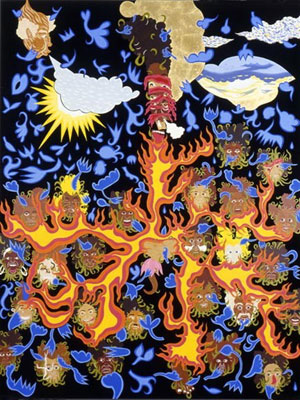

William Villalongo...Earth, Wind, & Fire...2006...Acrylic and paper on velvet...96 x 72 x 3 inches...Courtesy of Esso Gallery, New York

Villalongo achieved a similar effect with Earth, Wind, & Fire: He has managed to evoke a biblical quality in a Day-Glo painting on black velvet that speaks to the impact of Hurricane Katrina. Disembodied heads bob against the black ground, linked by a web of fire and bright blue organic shapes. The cartoonish faces alternately grin and grimace, making it difficult to tell if they’re dead, alive or somewhere in between. Villalongo thereby has brought in hope as well as humor, blending African-American pop culture references with the harsh reality that lies behind his allegory in one of the show’s best works.

Maysles has used a very different strategy to monumentalize pop culture. He based Bedroom Poster on a photograph of Larry Bird and Julius Irving grappling on the basketball court, which he found on a T-shirt sold in Harlem. Blown up on the canvas and painted in rich hues of blue, the image is unmoored from its historical context and takes on significations that run deeper than an interracial sports feud.

Themes implicit in Hancock’s painting are highlighted within the context of the work by Maysles and Villalongo. Sesom’s Mission is part of an ongoing series that tells the story of the Vegans, who have sworn off all pleasure, meat and color, and their enemies, the Mounds, a product of the union between humans and plants. Sesom, a Vegan who has been visited in his dreams by another of Hancock’s characters, Painter, embarks on a journey to find the Mounds. The story unfolds in the painting through text layered over an image of a Mound, a towering black and white striped shape crisscrossed with ribbons of color. Sesom’s journey takes on a biblical cast within the text, as if Hancock’s character were a latter-day Moses, while the politics of race simmer beneath the artist’s larger story of two warring tribes and their conflict over color.

One of the great things about The Sirens’ Song is Baum’s installation design, which juxtaposes paintings in terms of thematic content, narrative strategy and more superficial factors, including color. Each work draws out complementary, at times surprising, aspects of the others. The extraordinary coherence of the majority of the show, however, makes the few inconsistencies especially glaring. The dreamlike, personal narrative in Chronicles of Certain Importance—the best days leading up to my prom date (Inside the Shell gas station kiosk) by Xiomara De Oliver, which pictures a group of women clad in bright yellow dresses who appear to float against a red ground, has little or no relation to Alverson, Fauerso, and Efrat’s meditations on violence, although De Oliver’s painting certainly fits within the exhibition’s broader theme of storytelling. The same problem applies to the work by Kirk Hayes. Existential Penguin and Only a Flesh Wound, Love are great fun to look at—Hayes is a master of trompe l’oeil and certainly had me fooled with his mimicry of collaged cardboard—but they detract from the otherwise tight network of correspondences that reverberate among the paintings installed in Arthouse’s larger gallery. The Strongest Man in the World is He Who Walks Alone, from Vincent Valdez’s Stations series, hangs in relative isolation near the gallery reception desk. This is a dark corner for a work that is apparently a substitution (the exhibition’s promotional materials instead show Expulsion from the Great City by Valdez, two drawings of nude figures that represent Adam and Eve).

Ali Fitzgerald...A Trench Coat...and its Body Stall at our Gate...2006...Gouache, acrylic and marker on canvas...95 x 211.5 inches

The exhibition’s two installation works are placed in architecturally discrete spaces that give them ample breathing room. Hilary Wilder characteristically has combined painting on canvas with painting directly on the wall. A Castle Dark, Sunset references the biography of Cathy Smith, a Gordon Lightfoot groupie who was also involved in the death of John Belushi. Wilder’s atmospheric painting appears dark and foreboding, qualities shared by A Trenchcoat and Its Body Stall at our Gate by Ali Fitzgerald. The two canvases that make up A Trenchcoat… are suspended from the ceiling, staggered one in front of the other, creating a floating impression that dovetails nicely with the headless figures and huge airplane that populate the work. Both installations, but especially Fitzgerald’s, seem like a bad dream: Some of what’s happening feels familiar, but nothing adds up.

Dreams don’t tell us anything so much as show us something, combining fact and fiction in disturbing ways. The fluid relationship between the real and unreal is manifest again and again in The Sirens’ Song. At the curator’s talk for the exhibition, Baum related a statement by Wilder on how we make memories by conflating known facts with what we wish were true. Taken as a whole, the work in this exhibition operates more in the vein of a nightmare where our worst fears run rampant. If we tell stories to make sense of the world, then there’s little comfort to be found in The Sirens’ Song, except the pleasure of a well-conceived exhibition.

Images courtesy Arthouse

Amanda Douberley is a PHD student in Art History at UT Austin, and a Contributing Editor to Glasstire.