If, as Heraclitus pronounced centuries ago, 'you can't step into the same river twice,' then the Austin Museum of Art's recent joint exhibitions entitled Over + Over and Again + Again have a bit of explaining to do.

Nam June Paik... Zen for TV ... 1963/2000... Prepared TV set... 18 3/4 x 17 1/2 x 11 inches... Collection of Austin Museum of Art... Photo by Jeff Rowe, Austin Prints for Publication

If, as Heraclitus pronounced centuries ago, "you can't step into the same river twice," then the Austin Museum of Art's recent joint exhibitions entitled Over + Over and Again + Again have a bit of explaining to do. For a process to be authentically and precisely repeated, for all things to truly remain the same, it seems we must assume a static state of material change (and artistic license) along with a stiflingly still sense of time. Interestingly enough, the foundations of classic scientific theory, the one you learned and memorized in high school, which involves data mining, hypothesis posing, experimental accuracy and truth confirmations, is based on this same principle of static repeatability: for a thing to be verifiably true, more than one scientist must be able to arrive at the same conclusions by the same experimental means. But if (as quantum mechanics suggest) materials, persons and circumstances are changed in the passage of minutes, even seconds, then between the time I put one foot in Heraclitus' river and step down with the other foot, the world and my being in it are altogether different. Still, as AMOA director Dana Frïs Hansen's curating of Again + Again illustrates, there is history, some sort of building process wherein the current moves in art, whether illuminated by tactile materials or rethought in light, film, digitization and sound, that becomes an unrepeatable repetition. An 'Again' that can't occur at any other time and still be the same, but also that can't exist without what came before.

With these issues and questions in mind , I took the opportunity to interview Frïs-Hansen about Again + Again, the precedents for its works in experimental film and some of the implications of the show, given its critical piggybacking with Over + Over, the joint Krannert Art Museum and AMOA exhibition.

Nikki Moore: While both Over + Over and Again + Again speak to the new and the now, each show has more fundamental origins in experimental art of earlier times. Can you give us a little background on some of the pieces in Again + Again ?

Dana Frïs-Hansen: The curators of Over + Over open their catalogue this way: "As the digitized images on the plasma screen become the ubiquitous means of communication, and the keyboard supplants the hand, a number of artists draw inspiration instead from the tenets of the Arts and Crafts movement of a hundred years ago.… [creating works] informed by Process Art of the 1970s, and attached to the grid that has organized much of the art of the last fifty years…."

Just as the Over + Over artists have their roots in the history of art objects, the artists who work with less tactile material also connect with these artistic traditions and genres. I see Nam June Paik as an heir to John Cage's music and chance theory and Robert Rauschenberg's altered found objects. Christian Marclay connects to political photo-collagists such as John Heartfield, but also to Sergey Eisenstein's film montage. Burt Barr extends Andy Warhol's real-time films such as Empire, but is also connected to the process-oriented sculpture in the late 1960s that dealt with form and formlessness, including the work of Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman, and Alan Saret, where situations were set up and then allowed to play out as nature asserted its forces. Dane Picard and Jim Campbell's works deal with portraiture and change, Jason Salavon's with still-life. And Barna Kantor examines movement in a landscape-like field.

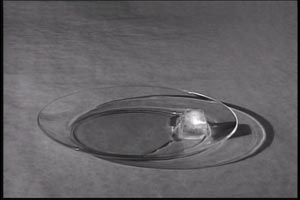

We can also talk about tools and time. While all of the works in Over + Over are tactile and time-consuming, and use the hand and often a handheld tool (knife, glue gun, drill, etc.), the creation of the Again + Again works with video and light consumes time and technology in different ways. For example, Paik's Zen for TV (1963/2000) and Barr's The Long Dissolve (1998) are very conceptual and low craft. A few wires in the back of Paik's television are clipped (by a television technician), and the installer turns the TV on its side, and the work is done. Barr places an ice cube on a plate in front of a camera he's turned on. Other artists spend hundreds of hours in an editing suite or on their computer, using complex technical processes to manipulate existing images or to generate new and changing virtual realities.

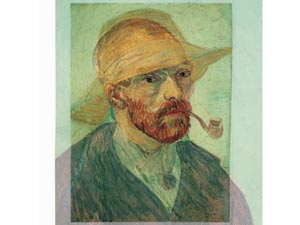

Dane Picard... Vincent Van Gogh: 42 Self-portraits (detail) ... 2004...54 seconds... 35mm... Collection of Deborah Green, Austin...

NM: If we think about technology as a mere tool, is it safe to say that both shows are working with technology in their own ways? Do you see the historical move from tactile tech to light, sound and digital media as a fluid transition or as a jump … and in what ways might one of Again + Again's works lead you to your conclusion?

DFH: The historical move to technology by the artists in Again + Again is neither fluid nor a jump, but rather jumping around! For each issue or concern that we might address with these shows (tools, technology, time, craft/process, materiality), there is a continuum on which the works fall. And that's a good thing. For example, in terms of process, within this show you find altered, light-producing objects (Paik, Kantor), straight recordings of events staged before a camera (Barr, Macdonald), computer-generated, abstracted images which unfold in either a programmed or a randomized sequence (Campbell, Salavon, Steincamp), and meticulously edited still or moving images (Marclay, Picard).

Speaking about artists working with video, John Baldessari wrote in the 1970s, "For there to be progress in TV, the medium must be as neutral as a pencil. Just one more tool in the artist's toolbox . Another tool to have around, like a pencil, by which we can implement our ideas, our visions, our concerns." One reason I did Again + Again was to show that many of the concerns and impulses found in Over + Over are found in works in light and video, too, and they shouldn't be discriminated against or separated from the mainstream. Curatorially, we had space to fill in the museum because Over + Over didn't fill all our galleries; I chose to respond to the Over + Over curators' premise that their artists are separate from technology by celebrating some artists who use the ephemeral materials of light and video with some of the same impulses, including absurd and enigmatic repetition; familiar, everyday objects transformed in unexpected ways; and immersive expanded visual fields. Furthermore, it's a great opportunity to show nine great artworks from AMOA's and the community's collections to a much wider audience.

NM: How does the role of the artist shift, if it does indeed shift, between Again + Again and Over + Over ? And the role of the viewer?

Burt Barr... The Long Dissolve ...1998... 9:15 minutes... Black-and-white video, no sound... Collection of Michael and Jeanne Klein, Austin... Photo courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co, New York

DFH: This is an important question as it brings up the old bugaboo about the importance of 'the hand of the artist.' Is the 'artistic genius' found in the wrist or in the brain? Is it a Rubens or a Rembrandt if the master didn't finish off the highlights, put down instead by his studio painters? Or is a metal box designed by Donald Judd but fabricated by a factory still a work by Judd? Are Christo and Jeanne Claude's installations less (or more?) interesting because they involve the participation of hundreds of workers through each step of the process? I think that, again, there is a continuum of artistic involvement and that this should enter into the discussion of each work on a case-by-case basis. While Liza Lou hires help with her beading, Shakia Booker has studio assistance. Lisa Hoke came alone to Austin and mounted the cups herself, while Rachel Perry Welty mounted her twist-ties after our crew nailed a ladder of nails for her. Elizabeth Simondson's mother regularly works alongside her to help plug wires in the wall.

With the works in Again + Again, the artists were dependent, to differing degrees, on both technology and technicians. We no longer need to know how a tool works in order to use it in brilliant ways toward the ends we seek to achieve! The key point is that the artists have the final say or signoff on a work under their authorship. In his 'Paragraphs on Conceptual Art' ( Artforum , June 1967), Sol LeWitt, another artist who allowed others to bring his artistic ideas into being, declared, 'The idea becomes a machine that makes the work.' This is an idea which has taken root and continues to blossom in these works and what will follow.

NM: As it seems to include, yet go beyond, sheer entertainment, what do you make of the humor inherent in Again + Again ?

DFH: I find both comedy and tragedy in these works. Wonder and despair. Resonances that connect with our humanity in the ways that great art has always done. A few examples: Picard's Vincent Van Gogh: 42 Self portraits (2004) spins through years of searing self-examination in 54 seconds — talk about mood changes! But there's more — especially when the work is put opposite Campbell's Portrait of Claude Shannon (2000), which shifts from solid form to random flashes of light to solid again, leading us to think about corporeal presence and absence. And what a portrait can tell about the sitter. As Vincent goes through his schizophrenic spins, beside it the not-so-still-life by Salavon is changing at a barely perceivable rate. Marclay shows us the many ways humans interact with the common telephone, and all the emotion that can be projected onto placing and receiving a call. Through the way he's cut the scenes, high drama becomes high farce, and yet I think there's a poignancy embedded in that work about the ways we connect to each other telephonically. On the other hand, there's a quiet, solemn quality in the way Paik and Barr's work demands patience, but there's a poetic irony, maybe even absurdity, too, with the titles that carry an exaggerated gravitas. And wonder, which is so necessary these days, is prompted at the start and finish with the ever-changing, always-random patterns created by Steincamp and Kantor.

NM: Were there other issues you were thinking about when you were putting together the show?

DFH: The show started with the recently acquired Kantor work, which I really wanted to show because of its visceral impact and accessibility. Ideas about the variety of light that artists work with today spun off from that, including different types and sizes of monitors and projections, plus the flashing LEDs of the Campbell work and the seemingly static line of light of the Paik installation, which is actually generated by live broadcast television. The idea of motion in and of itself was connected to the genres of portraiture, still-lifes and abstracted fields. I wanted our regular viewers to make connections to works we've previously had on view, including the flower curtains of Jim Hodges and the time-stretched screen tests of Andy Warhol or Chuck Close's gridded self-portrait. Floor space was limited, so I couldn't show Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler's brilliant Single Wide (2002), which would have been perfect and has never been shown in Austin. It was impossible to limit sound interference, so I decided because Marclay is both a visual and a sound artist, the incessant ringing and answering of telephones, over and over, again and again, would become part of the exhibition environment, and the only audio you'd hear.

Images courtesy AMOA.

Nikki Moore is a writer currently living in Austin.