Camp Fig, which enjoys a great location in downtown Austin, seems to be the ideal venue for a two-person show. The gallery is small, but it has a strorefront façade, and it is managed by a young and enthusiastic group of people.

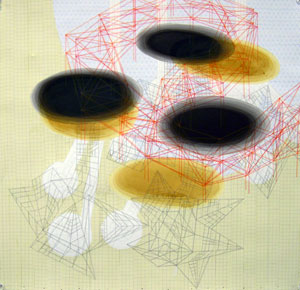

Eric Zimmerman... Untitled (Complex A)... 2005... Ink, pencil, pen and collage on paper... 15 x 15 inches

Brant Watson and Eric Zimmerman’s show of new work at Camp Fig recently was a fitting exhibition for the gallery. Overall, the show was a breath of fresh air in the sense that it was simple and clean—no bells and whistles, and the work offered subtle and well-thought connections between the two artists.

Brant Watson and Eric Zimmerman are printmakers, but their show was an exhibition without prints. Both artists chose to exhibit drawings and sketches, and while quite different visually, Watson and Zimmerman’s works on paper reflect a shared mentality that is due partially to their common background in printmaking. This is evident in each artist’s approach to his materials. Both employ fine lines with the exactitude and intricacy that comes from hours bent over a copper plate with a burin. But in addition to this certain stylistic coincidence, both Watson’s and Zimmerman’s drawings, like etchings or engravings, are the products of long and careful processes of ritual and repetition involving their chosen media and their source material. Ultimately, this commonality of practice links each artist’s drawings physically to their conceptual origins.

All of Watson’s drawings and sketches that appeared at Camp Fig can be traced back to one initial point: the experience of watching the trilogy of Spaghetti Westerns directed by Sergio Leone and starring Clint Eastwood: Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Watson’s memories of these films are linked to his childhood, and they shaped his conception of the western landscape. Captivated by Eastwood’s mythical image as an American hero as seen through the lens of an Italian director, Watson in his work seeks to distill this myth even further. His drawings at Camp Fig are certainly derived from Leone’s films: on one large sheet, the word “pistol” is written delicately over and over in minute script, until a tangled and nebulous image emerges. Watson repeats this process in another drawing with the word “Sergio.” The images have the distinctive visual quality of highly ordered chaos, at once deliberate and random. These two drawings also betray the artist’s highly romantic attachment to the films; Watson maintains a habit of watching them over and over as he sketches, sometimes transcribing characters’ dialogue. His drawings are a direct result of such transcription.

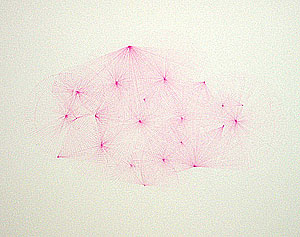

Watson’s obsessive practice of sketching with the films has yielded other images whose connections with the Leone trilogy are less immediate. Another drawing from the show is made up of light blue circles each with lines radiating from its center to its outer edge. The image produces the same visual effect as his word drawings, and Watson admits that the shapes are actually wagon wheels, another image from his memory of the “Old West.” I say “memory” because Watson has adopted these films as a part of his own personal history. He consciously co-opts them with the understanding that his idea of these fictions is merely his perception of an idea (the myth of the Old West) as seen through the filter of film. For Watson, this filter does not depreciate the value of the films for him as belonging to his catalogue of personal, firsthand experiences.

Zimmerman’s drawings explore similar ideas about memory and perception. His work is also largely about an idea of the Western landscape, but his images, like his memories, do not draw from the filmic myth of the West. Instead, Zimmerman’s sources are photographs from his travels across the country, and maps of these areas. By combining these visual interpretations of place with his own memories, Zimmerman seeks to recreate in his drawings a composite image, representing a psychological rather than physical space. His images are recognizable as landscapes, but only in their essential formal elements. The drawings at Camp Fig, for example, all contain the same three components: strips of paper, concentric elliptical pools of ink, and complex linear formations of ink and graphite that wind over the strips of paper and through the pools of ink. Each drawing offers a unique variation of these elements, but they all combine to form roughly the composition of a landscape. The strips of paper––blue and white graph paper and the yellowed margins of old books––divide the ground into land and sky. The elliptical pools of black ink, which are ringed with yellow, seem to float over the foreground and into the horizon. However, the fantastic linear structures snake over the ground and slice into the ink pools, and this confounds any pretense of perspective; the entire composition flattens into a maplike abstraction.

Zimmerman’s combination of traditional landscape imagery and cartographic elements underscores the fundamental subjectivity that is involved with all perceptions of place, whether they be in personal memory or in other more naturalistic representations. Watson’s further confusion of the differences between “real” memories and memories of films provides a fitting juxtaposition which placed them in a fortuitous These two artists, then, were in a great position for showing their work in the same venue, because their work is only slightly similar stylistically, but conceptually complementary.

Images coutesy the artists

Chelsea Weathers is a writer living in Austin.