Is there another American photographer who’s given us as many iconic images as Diane Arbus?

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971)... A young man in curlers at home on West 20th Street, N.Y.C. 1966... Copyright © 1972 The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

Robert Frank, perhaps. Walker Evans would certainly be in the running. But, arguably, they – and others – are known for a body of work, Frank principally for his great book, The Americans, and Evans for his contribution to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. And even those projects are remembered by one, maybe two, photographs that stand as signifiers for the whole. Reductive, I know, but that’s how culture works.

But say “Diane Arbus” and the images that come into focus are particular. Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. 1962. Teenage couple on Hudson Street, N.Y.C. 1963. Boy with a straw hat waiting to march in a pro-war parade, N.Y.C. 1967. Identical twins, Roselle, N.J. 1967. Man at a parade on Fifth Avenue, N.Y.C. 1969. A Jewish giant at home with his parents in the Bronx, N.Y. 1970. In part, that particularity is a consequence of the prosaic specificity of the titles, the descriptive deadpan with which they fix their subjects to a particular point in space and time. Even if you don’t remember the titles exactly, they fix the image in your memory. Take away the titles, as she did in one of her final series, and her photographs are still haunting and unforgettable. (I mentioned to a friend that, while I could no longer tell you the image, I still remember my experience of seeing an Arbus photo for the first time; he agreed to a similar memory.)

Diane Arbus: Revelations, now on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, has all the photographs invoked above and many more that should become iconic, now that Arbus is back in the spotlight. Organized for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art by co-curators Sandra Phillips and Elisabeth Sussman, the exhibition is the most complete presentation of Arbus’ work ever assembled, and the first since MoMA’s 1972 retrospective, the year after her death. It is a stunning, if worshipful, show.

Arbus was born Diane (pronounced Dee-ann) Nemerov in New York City in 1923. She began taking her first photographs in the early 1940s – one of the earliest photos in the show, from 1945, is a self-portrait, pregnant, taken via a mirror to send to her husband Alan Arbus, stationed overseas with the Army – and later studied with Berenice Abbott and Lisette Model; the latter’s workshop, taken by Arbus in the mid-fifties, inspired her commitment to photography.

The exhibit wends through six galleries, punctuated by three “libraries” which contain photographs, magazine clippings, contact sheets, books from Arbus’ personal library, works she owned by other photographers, her cameras and her enlarger, and quotations from journals, working notebooks, and published writings. It’s interesting, and frequently illuminating, but these “libraries” have a bit too much of the shrine about them. The objects are offered up to us as relics of the Patron Saint of Post-War American Photography, Ah-men. It’s clear that this exhibition intends to be definitive, to be the starting place for any future Arbus scholars (for example, the sumptuous catalog contains a thorough chronology), but these punctuations come as interruptions; one wishes that they could have been separated from the photographs. (It should be said, even with this caveat, that curator Ann Wilkes Tucker has done a beautiful job with the materials given her.)

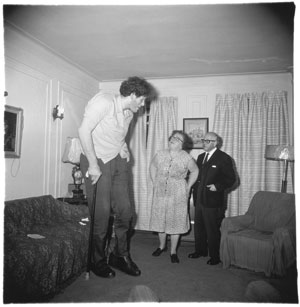

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971)... A Jewish giant at home with his parents in the Bronx, N.Y. 1970... Copyright © 1971 The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

From the beginning, Arbus’ vision was singular. The first room of the exhibit contains her earliest work (though the exhibit is not arranged chronologically), before she developed the intimate portraiture that would become her trademark. But already some of the subjects and themes that would concern her are apparent. She’s already drawn to the sideshow “freaks” and female impersonators, subjects that would define her work. And intimations of her mature portrait style can be seen in photographs like A woman on the boardwalk, Coney Island, N.Y. 1956 and Child in a nightgown, Wellfleet, Mass. 1957. But some of the images are atypical for Arbus. 42nd Street movie theater audience, N.Y.C. 1958 is shot from the well of the theater, looking back up and across the audience, the projector’s light illuminating the moviegoers, all of them sitting away from one another, alone together in the dim theater and the haze of their cigarette smoke. There are other shots taken in movie theaters, one, from 1958, of spectators watching burning crosses in a newsreel. Other photographs – of an ornate, empty movie lobby, of an empty funhouse, of a castle and of rocks on wheels at Disneyland – speak to Arbus’ fascination with the theatrical that informs all of her work.

In the introduction to a 1961 photo essay for Harper’s Bazaar, Arbus makes a statement about her subjects for the essay (five very decided eccentrics) which could stand for her entire project: that her subjects are people who lead us to “wonder what is veritable and inevitable and possible and what it is to become whoever we may be.” She was drawn to the theater of the self, the distance between who we would be and who we are, between how we see ourselves and how we are seen; hence, her fascination with female impersonators, transvestites, the circus and sideshow, high society hoi polloi and downtown demimonde. Her portraits are braced with a combination of cool, detached observation and compelling empathy. (But not always – she could skewer pretension, as well, as in her portrait of a young Norman Mailer, in a three-piece suit, one leg tossed over the arm of the chair, the alpha male “presenting.”) Those unsparing qualities appear in different proportions in her work. Often enough in these photos, the freakish seems more “normal” than does that which would be considered so. Of freaks Arbus said, “Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life.” The freaks possess an integrity of self that is a gentle rebuke to the more conventional people in these portraits, a rebuke to the freakishness of conformity. Yet all of these portraits are infused with melancholy, born out of awareness of that distance between the projected self and the perceived self, and the fragility of the whole charade. Arbus’ portraits carry a whiff of mortality; she had the rare gift (or curse) to see the skull beneath the mask while never falling into nihilism, able to step back from the abyss and recognize the brave necessity, the affirmation, even, of the mask.

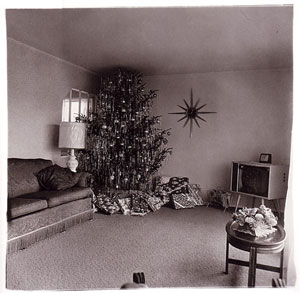

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971)... Xmas Tree in a Living Room in Levittown, L.I. 1963... Copyright © 1967 The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

By all accounts, Arbus was meticulous about her prints, although she only printed her own in the last three years of her life (and, when she did, she even went so far as to mix her own chemicals from scratch). Still, she never kept notes. Every time she reprinted an image, she worked from memory; no two exhibition prints from her lifetime are precisely identical. There’s something touching about such faith in memory, a confidence that the photographer’s eye and instinct will know the right moment. Keep that in mind if you find yourself thinking that some of these images seem underexposed, like Child selling plastic orchids at night, N.Y.C., 1963. What you see is exactly what she wants you see.

The combination of empathy and clear sight might also explain why, alone of 20th century photographers, Diane Arbus’ photographs can remind us of some of the great European painting masters. I’m not going to play mix-and-match, but merely point to two photos. Identical twins, Roselle, N.J. 1967 could have been painted by Murillo, while Untitled (7), 1970-1971, the last photograph you pass on exiting the exhibit, could be a dance of holy fools, those mental deficients believed to have been touched by God, as painted by Velázquez. Like all great artists, Arbus was a seer whose vision sears your own perception, altering it forever.

Of all the iconic images in Revelations, of all the poignant, joyous, eerie, or sad pictures in this landmark exhibit, one in particular stays with me: Xmas tree in a living room in Levittown, L.I. 1963. A too-tall Christmas tree, cut short on the top, stands in the corner, surrounded by wrapped presents, squeezed in from the left by the sofa and an invisible end table whose presence is indicated by a lamp whose shade is still wrapped in its protective cellophane. To the right of the tree, a starburst clock hangs on the wall between the tree and a spindly-legged TV. The viewer is situated almost directly between the arms of an armchair in the immediate foreground. Between the viewer and the TV is a small table with a low dried flower arrangement sitting on a lace doily. The pattern in the wall-to-wall carpet is echoed by the texture of the sofa, on which a large throw pillow suggests the absence of a recent presence. It’s perhaps the saddest picture I’ve ever seen, and I’m still trying to figure out why.

All images copyright © The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC.

John Devine is a writer living in Houston.