In spite of the wealth of media artists use today, painting remains the one by which we judge the health of contemporary art. If you don’t believe me, recall for a moment the embrace of neo-expressionism in the 1980s: how relieved the art world was to emerge from a decade-long diet of minimalism, conceptualism, and performance art.

Inka Essenhigh, Scorched Sun, 2001 ...Oil enamel on canvas, 74 x 70 inches...Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York and Victoria Miro Gallery, London

Or ask yourself when you last heard someone complain about Documenta or the Whitney Biennial not including enough photography or video, while these same shows are lambasted for not having enough painters. Or count the number of times in the last 10 or 20 years you’ve heard the phrase “the New Painting” used, as if merely intoning the words will bring about the second coming of the medium. From the time of Leonardo da Vinci, painting has lodged itself in the popular view as the highest form of visual art. But today the very idea of a hierarchy of media is as antiquated as the time when such claims were first made. Even so, painting remains the wealthy patient of the art world, getting the best medical attention, its vital signs regularly checked and its diagnosis frequently pronounced. With Pertaining to Painting, it’s time once again to check in on the patient.

Though she refrains from a rigorous curatorial premise, curator Paola Morsiani in her brief catalog essay offers a useful point from which to begin examining these pictures. She describes the willingness of these nine painters to “look at the history of painting.” Their appraisal, she continues, is not iconoclastic in the classic Modernist, kill-your-idols sense. They are respectful without being deferential; they acknowledge their forebears, but remain true to their own purpose and voice. But contemporary art could use a little iconclasm these days, and this show is no exception.

Thomas Nozkowski, Untitled (7–122), 1999 ...Oil on linen on panel, 22 x 28 inches...Courtesy the artist and Max Protetch Gallery, New York

Two broad tendencies linking the artists in varying degrees to historical precedent can be discerned in Pertaining to Painting. The first is abstraction, as seen in the work of Mark Bradford, Inka Essenhigh, Hilary Harnischfeger, Udomsak Krisanamis, and Thomas Nozkowski. The second is Surrealism, as evoked by the uncanny paintings of Michaël Borremans, Nader, Neo Rauch, and Sigrid Sandström. While both tendencies are associated with specific historical movements, their vocabularies have persevered, weathering the storms of artistic fashion and becoming part of the larger language of contemporary art.

Though Inka Essenhigh works in an abstract idiom, the similarities of her imagery to that of Francis Bacon are a more useful comparison than any abstract painter of yore. Both use only the parts of the human figure and its surroundings that interest them, and omit or obliterate the rest. Compare for example his Lying Figure with a Syringe to the reclining bather in her Scorched Sun, or his Painting (1978) to the shopper climbing into her car in her Mall Parking Lot. But where Bacon’s imagery is melancholic or horrific, Essenhigh’s is lighter and more playful; where his figures look blown away by a shotgun, hers have melted in afternoon languor. While the surfaces of these paintings are irresistible, Essenhigh isn’t a finish fetishist. Her surfaces lack a manufactured perfection — in places they are bubbly and textured, in others some underpainting shows through. Their glossy dazzle is the lure; her playful reworking of the vocabulary sets the hook. Essenhigh walks the line between representation and abstraction with the sinewy line of an access road and the gyrations of stumpy torsos playing volleyball.

, 2001 …Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 80 inches…Courtesy The Project, New York and Los Angeles”]

The other artists working in an abstract manner do so in a much less representational fashion. Thomas Nozkowski is the most old-school of these, painting Arp-like biomorphs and Miro-like patterns, but he explores abstraction’s most spent dialects and settled arguments. Mark Bradford’s paintings are more engaging, their layered surface reminiscent of disused billboards. The scorched, wrinkled papers he lays in overlapping grids create a reverberant effect that seems simultaneously static and in motion, like an aerial view of city blocks that can’t sit still. But elements like the hairstyle photos collaged into On a Clear Day I Can See All the Way to Watts come off as a superfluous afterthought. Bradford clearly wants us to believe that his work offers layers of meaning beyond his formal devices, but from these two paintings it’s hard to see what those might be.

Hilary Harnischfeger’s large wall collage, like those in her show last year at Moody Gallery, allude to the stylized clouds of Chinese landscape painting by way of glam rock baubles and a Barbie palette of pinks and purples. You can’t help feeling like the chef has run wild in the kitchen, grabbing at random from the spice rack: In a large pan, lay out several carved sheets of foamcore and Plexiglas; add five cups of plastic beads and a half-pound of glitter; wrap in polyester netting and bake for one hour; garnish with silver leaf and paint to taste. Untitled is like an inventory list from a craft supply store. The end result is a mess and the artist’s intention unclear.

From across the gallery, my initial reaction to the work of Udomsak Krisanamis wasn’t much better. It looked messy, gaudy, poorly crafted, and reminded me of something from the 1980s that I would have just as soon forgotten. Yet a closer look revealed a densely packed, highly worked surface of paint and collage that brought to mind the luxurious decoration of Gustav Klimt, the woven Manhattan traffic lanes in The Fifth Element, and the digital rain of The Matrix. Working in either a grid or cascade-like format, Krisanamis begins by laying down a collage of 0’s, 9’s, O’s, and P’s snipped from printed sources. He then obscures or obliterates all but the loops of those numbers and letters with acrylic or marker. The results are urban, aquatic, and digital. (According to the catalog, the obliteration process emerged from a technique the artist developed to learn English when he first moved to the United States from his native Thailand.) The technique sounds simple, but the variety and richness he achieves from painting to painting is extraordinary. Each has a push/pull dynamic that draws you into the details and forces you back to take in the whole. Of all of the artists in Pertaining to Painting reworking the language of abstraction, Krisanamis offers the freshest approach.

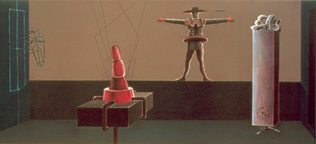

The only artist to directly quote from the classic vocabulary of Surrealism is Nader. Employing a familiar lexicon of masks, horses, clocks, picadors, alchemical devices, and iconic forms in a vaguely defined space, he puts the vocabulary of De Chirico, Dali, Picabia et. al. back into service, but to what end? A friend of mine in college was given an assignment by his art professor to paint a ‘surreal painting.” The results weren”t much different than these.

Michaël Borremans, The Conciliation–II, 2002 ...Oil on canvas, 25 9/16 x 19 11/16 inches...Michael and Judy Ovitz Collection, Los Angeles

While the remaining artists aren’t Surrealists in the historical sense, their work does show an affinity for the uncanny, the fantastic, or the dreamlike. The quiet, psychological set pieces of Belgian painter Michaël Borremans and the more dramatic dreamscapes of German painter Neo Rauch both portray moments of mysterious tension. Loosely painted in a chiaroscuro of browns and grays, Borreman’s paintings depict private, candid moments. They have a tension that tends more towards patient anticipation than thrilling portent. Borremans hints at the mystery of the ordinary. His characters play out mundane dramas made cryptic by the paintings’ omission of detail. We have a sense that something is happening but we’re not certain what or why. In Rauch’s work, the tension has broken and a swirl of activity has been set loose. Appropriately, the scale of these rambunctious paintings is larger and their palette more vibrant than Borreman’s, but an air of mystery, a kind of haze is preserved by the dry, chalky colors. Like a dream in which the elements of waking life are recombined into a new narrative, Rauch hybridizes socialist realism, personal iconography, and 1950s monster movies (Harmless could have been subtitled Attack of the Giant Gumball Man). His handling of paint is impressive, especially in Chase, where a squiggle of paint suggests the lapel of an overcoat, and a thin line of pale yellow suggests the first light of dawn.

Recently we’ve had a chance to see quite a few of Sigrid Sandström’s Nordic landscape fantasies. If she had worked for 70s album cover mavens Hipgnosis, Untitled could have been the record sleeve for Led Zeppelin’s Immigrant Song, its steam-filled ice cavern receding into outer space (Valhalla, I am coming…). The rich, red background and frozen column of blues in Man by Waterfall are so diverting that you don’t even realize it’s a landscape until your eye finally drifts down to the bottom panels. Still, her painting technique is disappointing: Sandström paints like a set designer. It looks convincing from anywhere in the theatre, but when you’re up on stage you discover that it’s only enough detail to sustain the illusion. Maybe that’s her point, but these paintings leave you feeling that she has the ingredients for some knockout work that she has yet to pull together.

So, how is the patient doing? A scorecard isn’t the most sophisticated way to measure an exhibition’s success, but it’s probably an accurate description of how we judge group shows like this one: if we liked enough of the art then it’s a “good show;” if we didn’t, then it’s not. As much as I like some of the work and appreciate the opportunity to see it in Houston, Pertaining to Painting is not exhilarating. To be fair, these pulse-taking shows rarely are. But if there’s no curatorial premise setting any boundaries on an exhibition, then shouldn”t it be a kick-ass selection of the absolute coolest stuff you can get your hands on? Perhaps that’s what Pertaining to Painting set out to be, but it left me feeling the same way a lot of other group shows do: happy to see some things I liked but somehow not fully satisfied. Where are the shows that thrill us with a slew of great work?

Images courtesy the artists and the Contemporary Arts Museum.

Chris Ballou is a writer, curator, and KTRU DJ working in Houston.