The just-closed Core Fellows 2001 show at the Glassell School was a Core circus: sound, video, performance, or movement featured in six of the eight Core Fellows’ works. In Duncan Ganley’s pseudo-museum, Jessica Halonen‘s circulatory system, and Fraser Stables‘ video installation, the action elements are permanent, while Trenton Hancock‘s painting performance, Betsy Coulter’s mime, and Brad Tucker‘s record player were one-night only events.

Betsy Coulter, Confidence Decoy #3, 2001…Decoy duck, paint, black screw, 7″ x 16″ x 6.5″…Courtesy the artist

In Betsy Coulter’s best piece, Confidence Decoy #3, a duck decoy with a round black eye sits on the floor next to a dark drywall screw in the baseboard. The screw mimics another eye, making the duck and the wall both parts of a curiously disorienting unfolded face like a cubist painting. Coulter’s simple means produce a vividly surreal effect which her other pieces aspire to but never reach. Confidence Decoy #4, a plastic deer balancing Styrofoam cup on its head and rump, evokes a quiver of shock at our casual disrespect for nature, but handsome pools of black and orange paint in the bottom of the cups move the piece one step toward neutral formalism. Likewise, Float, a cinderblock with milk jugs duct-taped to it, loses some of its rawness to overly formal composition. Archetypal lumpy materials are handled with a delicacy that negates their trashiness: the gray block and attached jugs are accented with a positively gorgeous bit of orange safety tape.

Duncan Ganley, Scene from “The Lost,”…(both imagined & undertermined), 2000-2001…Digital print on plexiglass, 30” x 40″…Courtesy the artist

Duncan Ganley’s fake movie posters, props, and computer manipulated photographs are presented in a fictional museum, making brilliant use of a familiar real-world context to unite his fictional artifacts and the didactic information which accompanies them into one seamless package. In the entertaining and well-paced audio tour which narrates Endless Filmset: A Prequel for an Unmade Documentary, Ganley’s soft, British accented voice describes the contents of each faked photo in progressively vague terms, beginning with a skewed overemphasis on a pair of ordinary chairs, gradually expanding to redundant absurdities such as the phrase “an authentic sense of genuine natural light” used to describe the “mirror room,” and ending with broad bits of non-information about a “top-lit panel by an unknown contemporary artist. . . The information label gives more information about this picture” all spoken in the same plausible, carefully enunciated tones. Well-written, well-performed, and well-presented, the piece is a screamingly funny satire of how a detailed and multi-layered media reality can generate and maintain its own self-referential existence without the need for any concrete facts at all.

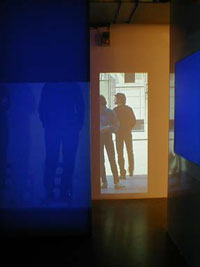

Fraser Stables” Three Scripts and Outside Voices overwhelm three short video projections with technology. A specially built room with exposed steel framing, a wall of stretched plastic, glowing light boxes, and exposed DVD projectors show three simultaneous videos: a pair of black-clad people standing on chairs, three men riding backwards in the bed of a pickup truck, and a downtown street as seen through a glass door with cars and pedestrians passing by. Overlapping soundtracks mingle disconnected phrases about sequence or sequins or standing on chairs. The three videos are so completely disjointed from one another that it is tempting to interpret the piece as a parody of art that uses excessive means to produce negligible ends; the two figures on chairs could be a wicked parody of the high seriousness of video art: they stand, anonymous, motionless, dressed in black, as the voiceover commands them to “talk to each other, but don’t answer.” The men in the truck sit silently, jostled by bumps in the road like a bored audience for the chair standers. By contrast, the realistic slice of life seen through the doorway, banal as it is, becomes an oasis of interest.

Trenton Doyle Hancock’s Torpedoboy Tries His Darndest to Stop an Oozing Moundment is a frenetic collage of words and hands cut from canvas and pasted together to form a tattered, dingy curtain the size of a tall wall. The piece’s humor and awkward gigantism leaven its grungy, angst-ridden technique with a casual silliness, which is lacking in the stilted wall paintings that surround it. Hancock’s improvisational wall paintings, executed in a space-filling but lackluster scrawl, make a pretense of self-revelation, but shy away at the last moment, substituting a vocabulary of unintelligible symbols (numbered trees, a disconnected narrative about vegans, moundmeat etc.) for bald autobiography, leaving the piece superficial and unaffecting. Genuine personal revelations can elicit sympathy or derision, but are always uncomfortable. I should have been a lot more embarrassed.

In Jessica Halonen’s Laps, intermittent loops of plastic tubing appear to circulate a pinkish fluid through the gallery’s walls and floor via a mysterious hidden pump. This is, in fact, the case, but I couldn’t rest until I knew for certain. Laps‘ faintly medical imagery is neutralized by the large scale of the tubing and its close relationship to the building’s architecture; what could have been a queasy surgical drainage is instead more of a clean industrial process. The piece elicits a few minutes of bug-eyed curiosity, but once the gimmick wears off, that’s it. Leandro Erlich’s Swimming Pool in the 1999 Core Show was just as simple but more thought provoking. Erlich’s piece took absurd pains to create its dumb effect, and we laughed sheepishly at ourselves for liking it even as we laughed at him for doing it, sharing a conspiratorial sense of absurdity. Halonen’s piece, since it isn’t laughing at itself, becomes a merely a momentary curiosity.

Some of Emily Joyce’s colorful shapes are on Plexiglas panels; some are directly on the wall, the wall stickers being vastly more interesting. Of her five pieces in the show, the best two combine wall stickers and painted plex panels; the three panels without wall elements are comparatively lifeless. Even in the two combination pieces, the wall elements would be better without their accompanying panels. In Stood the Grin, cutesy dinosaurs, stars and rosettes in brightly colored vinyl bubble out like a thought balloon from a painted plex square, but the interplay of framed and unframed images adds little to the work. By introducing overtly figurative and cartoon-referenced shapes Joyce moves her work a step closer to outright sticker-art, embracing the toylike playfulness her pieces have always had.

Brad Tucker’s best piece isn’t on display. At the opening, Tucker’s installation included a school-issue record player spinning a lopsided disc of gloppy green plastic. Listening carefully amidst the hubbub, one could discern a repetitive techno beat, or the record skipping, or both. With the craftiness of a high-functioning ape man, Tucker had cast his own copy of a Kraftwerk album in hobby store plastic, and it actually played, sort of. This low-tech deejaying added a dash of spirited irreverence to an uncharacteristically stiff set of Brad Tucker pieces. Without the record player, Tucker’s corner of the show takes on a formal seriousness out of keeping with the lighthearted manufacture of his works. Tucker’s pieces are too casual to be polished yet are presented too formally to be their funky selves. Individually, though, Tucker’s pieces are up to standard; Writers in the Schools is a curious monogram in retro polyester. Rockin’ Robin, a faked-up plywood practice amp has a clunky monumentality. A little too glossy, Al in LA curls across the wall like a rickety folk-art freeway, but needs only a little dirt and abrasion to make it just right.

It’s tough to make paintings that don’t look like art, but Todd Hebert manages it. A painter’s painter, Hebert gets off on nuances of technique that are largely irrelevant to his anesthetized imagery. Made with a jarring mishmash of illustration techniques, Hebert’s works have the patched together incongruities of work made for reproduction; velvety flat tempera-like paint, airbrush, and intricate linear rendering are all juxtaposed in the same painting. In Taller, a fluffy airbrushed snowman supports a lovingly woodgrained framework which in turn holds up a glowing orange jack o’ lantern, like creepy a still from a holiday TV special. In Ball and Leaves, an airbrushed basketball lies, as if forgotten, in an unnatural Technicolor leaf-pile. The kitschy pathos Hebert’s images and the arbitrary hyperintense color short circuit one another to leave an undefined sense of weird wrongness.

Bill Davenport is an artist and writer from Houston.