Vernacular networks drown institutions. Prestige-coded academic language, the gratingly soothing whisper of the entrepreneurial guru, and the oblique abstraction of art speak are all impenetrable, yet utterly transparent, word salads of feigned superiority. Such coded communication likely emerged as a natural defense mechanism — tribal, contagious, and oddly comforting in its alienation.

When I first read the title of Joseph Havel’s solo exhibition, all nouns become verbs, my brain kicked it back like a reflex. Corporate trauma flooded in. I hadn’t yet seen the show, but the phrase played a slow motion game of pool in my mind. As an institutional werewolf in recovery, I recall the cold sweat of the boardroom: a place where nouns get verbed until their souls whimper. If “leveraging impact” and “calendar that ask” don’t make you flinch, then congratulations, you’re either spiritually unbothered or deeply acclimated.

For example, here’s a sentence I once heard screamed in a glass conference room: “Can you calendar that ask and solution it by EOD?” Electric shivers down the spine.

But Havel isn’t that. As a leader and a friend, he lands in that special space between steadiness and kindness. Among my favorite qualities in educators, parents, executives, and friends, he remains steadfast, but does so with an air of gentle tolerance. He couldn’t be further from a corporate stiff. If his work speaks in code, it’s a syntax of touch, improvisation, and unpolished intuition. What struck me most — long before this exhibition — was his radical closeness to the shifting thresholds between things. He drifts not just across geographies, but mediums, moods, and metaphysical registers.

He lives in a house full of contradictions:

– A global traveler, a father to a majestic but mercurial parrot.

– A citizen of hodgepodge Houston and the hyper-curated French town of Ménerbes.

– A polyglot of painting, drawing, and sculpture who turns time into compost and language into gesture.

I could list more, but his show’s title already tells us: nouns become verbs. Havel doesn’t rest in his roles. He moves through them. And this exhibition — equal parts subset retrospective and revelation — traces that very migration.

The Grid as Gesture

The sixty-panel grid Kauai looks, from afar, like a mosaic of night fragments. Up close, each square reveals itself as a fierce micro-movement: oil stick swipes, pastel ghosts, neon scribbles, and voids. It’s a durational work, made over four years, one panel at a time — each a ritual, a breath, a collapse. Together they form a kind of time-lapse choreography, a serial accumulation that resists narrative closure.

Here, the noun (the panel) doesn’t freeze in form. It acts. Each square performs. If you look closely, you’ll find recurring motifs: irregular boxes, topographical stripes, diagonal punctures. These gestures don’t repeat so much as echo, like memories failing to stabilize.

To paraphrase my previous writing about Havel’s earlier show, Fantômes: drawing for Havel never serves as a plan. It haunts. It returns without permission. And in Kauai, each drawing’s repetition becomes a pulse, as if the hand wants to remember, but the body insists on forgetting.

The Folded Object

If Kauai whispers serial rhythm, Wash bellows the frozen aftermath of a gesture. Cast in bronze from a king-size bedsheet, the piece bends slightly, slack in its own rigid skin. Its surface reads like brushed snow or bleached flesh, fibrous and flesh-toned. It barely supports itself.

This is the paradox of Havel’s sculpture: how something so heavy suspends itself so lightly. The illusion recalls Rachel Whiteread’s negative space ghosts, but Havel’s bedsheet folds forward rather than inward. It doesn’t memorialize absence; it teeters on the edge of motion.

And here again: noun becomes verb. The object performs the memory of having fallen. And it continues to perform that fall, again and again, for as long as the viewer chooses to stand still and watch.

Scratched Cosmologies

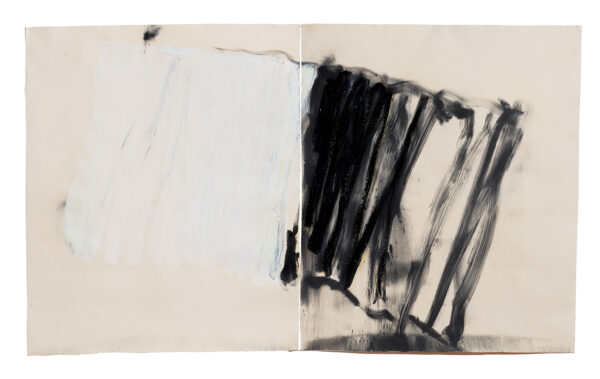

Elsewhere in the show, Havel’s drawings stretch out across time. One charcoal on paper piece, with a looming circular form crisscrossed by striations and loops, seems to chart the orbit of a thought as it collapses into itself. Another, starker composition pits a ghostly white block against a mass of black gestures — white as erasure, black as insistence.

Joseph Havel, “Summer,” 2020, oil stick, charcoal, and graphite on two sheets of paper, 60 1/4 x 100 1/4 inches

These are not studies. They do not serve sculpture. They aren’t preliminary anything. They are the work. These drawings remain distinct from his more formal cast-bronze pieces, which he creates with the assistance of a foundry. That distinction matters, because in drawing, Havel acts alone.

Spinning Signals

Perhaps the most literal noun-to-verb object in the show is a double-spiraled bronze structure that calls to mind a satellite dish mid-spin. Part Alexander Calder, part cosmic antenna, it twists upward like a body frozen mid-pirouette. The patina adds a greenish weathered texture, almost marine in effect. It feels both skeletal and musical.

And again: the noun acts. It spirals. It strains. It spins. It signals. The grammar of Havel’s work doesn’t follow subject-object rules. Instead, it loops. Noun slips into verb; verb returns to form; and form evaporates again.

This show doesn’t simply “pair” drawings and sculpture. It folds time. Each room gathers works made decades apart into a single shiver of resonance. Sculptures resist gravity, drawings exhale movement, and the viewer moves between them like a pendulum, or a ghost limb trying to feel what’s already been cut away.

In a city like Houston — where vernacular institutions rise, fall, and rebrand like startups — Havel’s show feels less like a retrospective and more like a ritual. A grammar lesson for those who still believe art acts.

And it does. Even nouns. Even now.

Joseph Havel: all nouns become verbs is on view at Josh Pazda Hiram Butler in Houston through May 3, 2025.