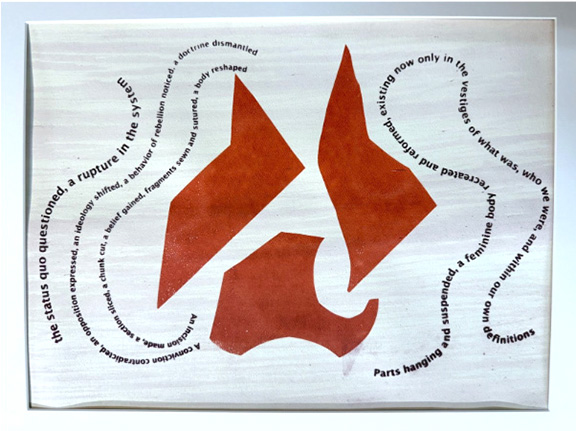

“It sort of resembles a woman’s pelvis,” I remark to San Antonio-based artist Olivia Ortiz. “Anatomical landscapes!” she exclaims. We’re looking at the exhibition poster for her solo show, Vestiges of Our Femininity, on view at Mercury Project in San Antonio and curated by Leslie Moody Castro. The poster features faint, light-pink striae covering the background, made by Ortiz hand-brushing cochineal onto paper. Then Ortiz screen-printed three nondescript red shapes, not quite touching one another but hovering in their central organization on the paper. To the right and left of the formation, Moody Castro’s screen-printed text orbits their irregular edges. Together, their cadence oscillates from the space between the shapes’ jagged edges and the text’s curvilinearity. The poster is illustrative of the collaboration between Ortiz and Moody Castro and offers a conceptual articulation of the featured works, all of which hinge on one key element: cochineal.

Olivia Ortiz in collaboration with Leslie Moody Castro, “Vestiges of Our Femininity” exhibition print, screen print with hand-painted cochineal on paper, 12 x 18 inches, 2025. Photo courtesy of the artist

In the 16th century, cochineal was known to many, but today, few are familiar with it (confession: I wasn’t). So, let me give you a quick rundown now that I’ve emerged from the cochineal rabbit hole. Cochineal is a small insect that dwells on cactus pads, typically that of prickly pear nopals. Female cochineals are flightless, living off the cactus’ juices and laying their eggs there. Cochineal produces carminic acid, a vibrant red pigment, so for thousands of years, the Aztecs and other indigenous peoples harvested the insect and its eggs for dying textiles, ceremonial use, and trade with other nearby native communities. When the Spanish invaded Mexico, they exploited cochineal as a natural resource because it produced a red hue that was more saturated than any found in Europe at the time. It became a globally traded commodity that was once more valuable than gold and silver, and ultimately became a symbol of power and high status. It was worn by royalty, military forces, and the clergy, and used to make paint used in European masterpieces. By the 19th century, synthetic dyes largely replaced its production, and today, only three cochineal farms remain in Mexico (“and they are all women-run!” Ortiz tells me). In Vestiges of Our Femininity, Ortiz employs cochineal as a personification of the feminine to chisel a new space that uncovers past exploitations and reveals forthcoming reclamation, free from the bounds of patriarchal constructs. The exhibition poster articulates this endeavor 4-fold, so I’ve italicized and bolded each section of the text to serve as section headers.

Olivia Ortiz, “All Day Everyday,” 2022-present, Conte on paper, 8.5 x 5.5 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist

The status quo questioned, a rupture in the system

In Ortiz’s self-described anatomical landscapes, materialized in drawing, painting, and installation, she continues the long tradition of depicting the female body in art. A fleshy palette proliferates through the exhibition space. Curving color fields hug into each other, tracing their contours. However, Ortiz’s subjects are not the odalisques and Venuses that populate the Western art historical canon. They’re abstracted as if one held a microscopic lens up to their body. Within the tradition of depicting nude women and their flesh, Ortiz offers a magnification that’s more intimate in context and perspective – a close-up of a body, a routine, or a life – but visually subverts that lineage because the work is not sexualizing the female form. In their obscurity, they disrupt the historical exploitative representation of women, shifting the flow of power back into their own hands.

A conviction contradicted, an opposition expressed, an ideology shifted, a behavior of rebellion noticed, a doctrine dismantled

Layering recurs in Ortiz’s work. In Stand Tall, six color fields of oil paint extend across the 72-inch canvas, each unfolding from the next, varying in form and color. The furthest-right field is a deep oxblood color, which Ortiz tells me is the same color as pure cochineal pigment. The following color fields moving leftward represent the value scale of cochineal; the hue lightens as additives, such as acid, are added to the pigment. The resulting tonal gradient implies a kind of episodic trajectory, like age in a lifespan, phases in a menstrual cycle, or eons on a larger geological timescale, which makes me think of another applicable phrase complementary to Ortiz’s anatomical landscapes: sedimentary femininity. The flat perspective, allowing all layers to be viewed at once, translates as a moment suspended and removed from its trajectory, enabling a conceptual third-party reflection on how layers of past constructs of femininity have lifted us to the surface of today’s gender discourse. From this vantage point, women possess the agency to usher in what remains useful and shed what’s become obsolete as they craft their identity. Ortiz’s reference to cochineal in the gradient exemplifies the power shift in this trajectory by usurping its colonial exploitations to instead shroud in power those marginalized by its patriarchal principles, notably, indigenous people and women.

Oliva Ortiz, “And Never Back Down,” 2025, 60 x 72 inches, oil on canvas. Photo courtesy of the artist

An incision made, a section sliced, a chunk cut, a belief gained, fragments sewn and sutured, a body reshaped

Stand Tall’s composition is actually the inverse of And Never Back Down, which is drawn as a corset. With this in mind, their form comes to the fore. Horizontally oriented, the tonalites curve and zigzag into and around the next layer to form the shape of a woman’s chest and torso, with a bulge to outline the breast and indentations to accentuate the waist. In Ortiz’s work, the visual connotation of the corset functions in various ways. On one hand, it represents the ways that women’s bodies have been physically bound – to fulfill beauty standards and for medical recoveries – as well as the ways that women have been socially bound, and whose rights are still fluctuating to this day. As Stand Tall and And Never Back Down visually communicate inversely, Ortiz employs the corset inversely. Eschewing its historically inhibiting qualities and instead implementing the corset as a buttress, Ortiz reminds women not to bend to patriarchal pressures, especially in America’s present-day political environment.

From left: Olivia Ortiz, “And Never Back Down,” 2025, 60 x 72 inches, oil on canvas; Olivia Ortiz, “Just An Appendage,” 2025, sculpture mixed media, dimensions vary; Olivia Ortiz, “Stand Tall,” 2025, 60 x 72 inches, oil on canvas. Photo courtesy of the artist

Parts hanging and suspended, a feminine body recreated and reformed, existing now only in the vestiges of what was, who we were, and within our own definitions

Central to the exhibition space is Just An Appendage, an installation that is a newfound passion in Ortiz’s practice. Six swaths of canvas hang on bamboo rods suspended from the ceiling by string. Each canvas cut-out represents a body part or corresponding garment, such as a set of legs, a pair of panties, a lower back, side boob, and, again, a corset. After cutting the canvas by hand, Ortiz lined all of the edges in cochineal and then dunked them in a tub of clay slip to hold the form. The canvas hangs organically, with deep wrinkles in the fabric. Just An Appendage orbits the pole in the center of the room like a mobile, the six canvas pieces paralleling the six layers that compose the corset ribbing in the paintings Stand Tall and And Never Back Down. However, in the installation, those six elements are severed, like a deconstruction of the Frankensteinian construct of a Woman. The cochineal lining seemingly represents a kind of salve to this severance, alluding at once to both the historical exploitation and commodification of femininity and the healing work women must do to mend the inherited genetic trauma thereof, physically and emotionally. Now that those constructs have been deconstructed, Ortiz again brings us to that liminal space between what’s been determined for the female body up to this point, physically and collectively, and how women will define femininity for themselves moving forward.

From left: Olivia Ortiz, “Just An Appendage,” 2025, sculpture mixed media, dimensions vary; Olivia Ortiz, “Stand Tall,” 2025, 60 x 72 inches, oil on canvas; Olivia Ortiz in collaboration with Leslie Moody Castro, “Vestiges of Our Femininity” 2025, exhibition poster, screenprint and hand-painted cochineal on paper. Photo: Caroline Frost

From left: Olivia Ortiz in collaboration with Leslie Moody Castro, screenprint and hand-painted cochineal on paper, 2025; Olivia Ortiz, “And Never Back Down,” 2025, 60 x 72 inches, oil on canvas; Olivia Ortiz, “Just An Appendage,” 2025, sculpture mixed media, dimensions vary

Under a presidential administration that is pursuing a singularity in citizenship, religion, and gender conformity, plurality is crucial. Vestiges of Our Femininity demonstrates that as women pursue reclamation by inverting the systems historically used to homogenize us, we create a more heterogeneous social landscape by shedding layers that no longer serve its formation. Ortiz tells me that her daughters helped her sew the canvas onto the bamboo for Just An Appendage. “They were like, ‘Mom, I stabbed myself four times!’” she says. “Just like many women before them,” I add. Here’s to pricking fingers whilst crafting the way for the next generation of women!

Vestiges of Our Femininity is on view at Mercury Project in San Antonio through April 26th.