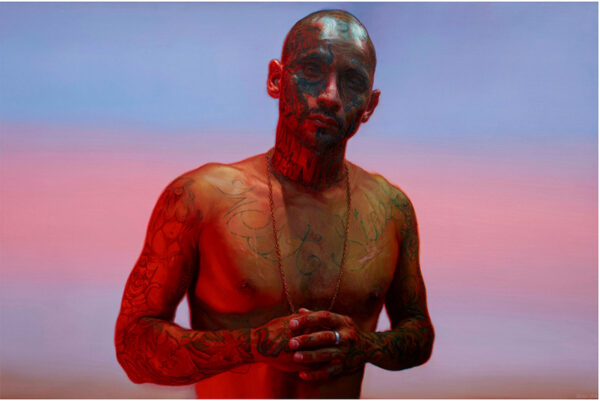

Vincent Valdez, “So Long, Mary Ann,” 2019, oil on canvas, Collection of Mike Healy and Tim Walsh, Santa Barbara, CA. Photo: Museum of Contemporary Art Houston

This is the story of three tattooed men, and in particular, how tattooed men of color are regarded in the U.S. We begin with Vincent Valdez’s So Long, Mary Ann (2019), which hung at the entrance to his recent exhibition in Houston (click here for my Glasstire review). The museum label connected the painting to Leonard Cohen’s 1967 song “So Long, Marianne,” with the following lyrics:

For now, I need your hidden love. I’m cold as a new razor blade

You left when I told you I was curious

I never said that I was brave

Oh, so long, Marianne. It’s time that we began

To laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again

The label, however, was mute regarding the story of the painted subject. I discovered that narrative in a videotaped lecture by the artist. Valdez explains that the man’s appearance would frighten most people, likely causing them to cross the street to avoid him. This man had spent much of his life in prison. Yet Valdez characterizes his model as “one of the most gentle people that I have ever encountered.” Moreover, the tattoos that wrapped around his body featured the name of his mother, Mary Ann, who had died when he was an infant. The tattooed man made her present by inscribing her name on his body multiple times.

Vincent Valdez, “So Long, Mary Ann,” 2019, oil on canvas, Collection of Mike Healy and Tim Walsh, Santa Barbara, CA. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Valdez quickly learned that the man’s personality belied the violent stereotypes associated with his body’s decoration. Just when Valdez decided to paint the man’s portrait, Cohen’s song fortuitously played in his studio. In Valdez’s mind, the two men were connected by the “universal tale of lost love.” Valdez insists that the tattooed man’s narrative is just as valid, meaningful, and important as Cohen’s.

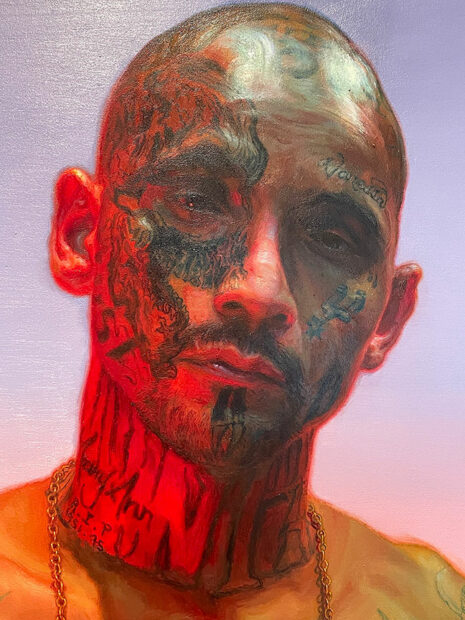

Photograph of Venezuelan immigrant Jerce Reyes’s arm, with soccer-themed tattoo, included in his immigration file. Image provided by his lawer, Linette Tobin, reproduced here from CNN.

The second tattooed man treated here is Jerce Reyes, a former professional soccer goalie in Venezuela. A crown atop a soccer ball is the emblem of the Real Madrid soccer team, and the word “dios” (god) refers to the soccer player Diego Armando Maradona (who claimed one of his goals was scored by “the hand of god.”).

Reyes, who affirmed that he was arrested and tortured in Venezuela after his participation in an anti-Maduro demonstration, sought asylum in the U.S. He traveled to Mexico and registered with the Biden administration-sanctioned CBP One app. But Reyes was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) when he arrived in the U.S. on September 1 for his appointment. In March, he was one of the hundreds of Venezuelan nationals who were characterized as gang members and who were sent by the Trump administration to the Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT) prison in Tecoluca, El Salvador. This notorious prison, with eighty persons per cell, has a reputation for humiliating prisoners and for torturing and sometimes beating them to death. The Trump administration paid 6 million dollars to Salvadoran President Bukele’s administration to incarcerate the deportees for a year.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) informed CNN that Reyes’s tattoos were “consistent with those indicating Tren de Aragua (TdA) membership.” A DHS official emailed the following information to CNN: “His own social media indicates he is a member of the vicious TdA gang.” According to NPR, Tobin says DHS flagged a common hand sign (posted twice by Reyes on Facebook a decade ago) that signifies Rock’n Roll as well as “I love you” in sign language. The DHS email to CNN also noted: “DHS intelligence assessments go beyond a single tattoo, and we are confident in our findings.” Tobin told NPR: “I’ve seen the evidence, and all it is is the tattoo and the hand gesture.”

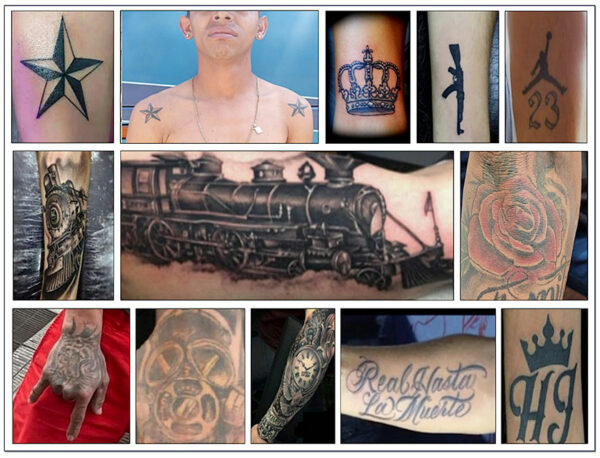

Tattoos the Texas Department of Public Safety (TDPS) regards as examples of the Tren de Aragua gang tattoos. Photo: Texas Department of Public Safety

The above illustration shows tattoos the U.S. government associates with the TdA (see pdf). It is unlikely that anyone in the government (state or national) has expertise in iconography nor an interest beyond leaping to the most simple-minded conclusions that would justify detaining Latinx immigrants. Reyes has a presumptive gang tattoo quadrafecta: a crown, a star, and the words “dios” and “real” (royal). (“Tren” means train, and had Reyes been a vintage train enthusiast, he might have had a locomotive tattoo as well.) The Wall Street Journal has contacted the families of seven men incarcerated at CECOT, who say they were arrested and deported on the flimsiest of grounds, such as a rose tattoo. One detainee’s misfortune came from an Autism Awareness tattoo.

Arresting Reyes on the basis of one or more tattoos and a common hand gesture is like arresting someone with tattoos that include a few random letters of the alphabet. Furthermore, Reyes’ tattoo artist informed CNN that he had burned the Real Madrid emblem on Reyes in 2018 before the Tren de Aragua was a known entity. Like other families of these deportees, Reyes’ family did not realize he had been rendered to El Salvador until he was identified through show-of-force footage shot at CECOT by El Salvador and reposted by the White House.

Furthermore, Reyes and other deportees were dubiously deemed to be part of a foreign terrorist organization under the Alien Enemies Act 1798, which has only been utilized three times in U.S. history, all during wartime circumstances, and never against non-state actors. For the details of the deportations, made in direct violation of a federal judge’s orders, see ABC News and Glenn Greenwald on Breaking Points. The latter so effectively underscored the importance of due process that he even convinced podcaster Joe Rogan.

The Trump administration claimed in February that the Venezuelan migrants it temporarily rendered to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, were “the worst of the worst” Tren de Aragua gangsters. As NPR notes, it later recanted these claims in court filings. White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt called the deportees to El Salvador “heinous monsters” and warned “illegal immigrants to actively self-deport, to maybe save themselves from being in one of these fun videos.”

Clearly, the Trump administration is engaged in a racist shock-and-awe campaign to terrorize Brown migrants by denying them due process en route to rendition to the most frightening gulags at its disposal. Cruelty is precisely the point. Such actions are also intended as spectacles: a circus cum Roman Colosseum form of theater designed to enthrall and excite the Trumpist base. Meanwhile, White immigrants — though they are not entirely immune to abuse — are not subject to comparable state terror campaigns.

Now, let us consider a third tattooed man, one who, at one time, was a bad enough hombre to be denounced by his own mother. This man has scarier-looking tattoos than Reyes, most of which are violent, either explicitly or by implication. These include a sword, muskets, and an assault rifle. The latter, were this man from Latin America, would be sufficient for the Trump administration to arrest and deport him. But this man is White and a citizen, so he serves as Secretary of Defense in Trump’s cabinet.

In addition to the Crusader tattoo on his chest, Pete Hegseth has a “Deus Vult” tattoo on his bicep, which means “God Wills It,” presumed to be a Crusader battle cry. Lydia Wilson of New Lines Magazine argues that Hegseth’s particular constellation of tattoos — described by her source Matt Lodder as “overt pseudo-revolutionary iconography together with militant Crusader history” — paints a “picture of militant Christianity.” Wilson adds: “Many of these symbols are ubiquitous among far-right communities, seen in events from the Charlottesville rally to the manifesto of the Norwegian far-right shooter Anders Breivik and the engravings on the gun of the Christchurch shooter.” Crucially, despite the long lineage of these images, “they have only been put together in the way they are seen on Hegseth’s body over the past decade, from around the time of Trump’s first campaign and ever more openly since.” Wilson interprets this cluster of tattoos as a form of visual doublespeak: as a unified body, they send a clear signal to Christian nationalists (and presumably to White supremacists) while, at the same time, the historicity of the individual images collectively function as a shield by offering plausible deniability.

Wilson quotes Ben Elley, an expert on far-right online radicalization, who says “that collection of symbols all together” is “very common in far-right communities.” Prevailing popular notions about the Crusades were invented by cosplaying Victorians. Thus, historian Charlotte Gauthier, also cited by Wilson, declares: “When the alt-right say they’re going back to the traditions of their ancestors, they mean — without knowing it — the 1880s, not the 11th century.”

Historian Eleanor Janega calls Hegseth’s tattoos “a call to religious violence.” Elley notes that the particular Christian symbols Hegesth has chosen are “symbols of a type of Christianity that defines itself against Islam.” As for Hegseth’s position, Lodder declares: “It’s both absurd and terrifying; terrifying that … someone with such prominent and worrying tattoos on their body is getting a Cabinet position in the U.S., but also absurd because it’s all very cosplay.”

In March, another Hegseth tattoo, the Arabic word “kafir” (infidel or unbeliever), was noticed underneath (and thus symbolically subjugated by) his Deus Vult tattoo. This discovery ignited a firestorm. As reported in USA Today, Nihad Awad, national executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, delivered a blistering statement, saying Hegseth “feels the need to stamp himself with tattoos declaring his opposition to Islam alongside a tattoo declaring his affinity for the failed Crusaders, who committed genocidal acts of violence against Jews, Muslims, and even fellow Christians centuries ago.”

Writing on X, pro-Palestinian activist Nerdeen Kiswani characterized kafir as a word used to “mock and vilify Muslims.” She concluded: “These tattoos aren’t harmless — they reflect the policies that continue to kill and oppress Muslims worldwide. This is the normalization of Islamophobia at the highest levels of power. What else is this supposed to mean besides U.S. foreign policy being a crusade against Muslims?”

As far back as the time of President Biden’s inauguration, Hegseth’s National Guard superiors deemed his tattoos to be so extremist that they removed him from a protective deployment. Additionally, there are reports of specific racist actions by Hegseth. In December, The New Yorker reported that in 2015, Hegseth, in a highly intoxicated state, had chanted “Kill All Muslims! Kill All Muslims!” in an Ohio bar.

With Pete Hegseth, we are left with a tattooed Crusading Christian fanboy wielding a terrifying amount of power, sober or not.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator.

6 comments

Good article! Makes a valid comparison that shows the bias and hypocrisy of society. The pointing fingers are attached to tattood arms!

Thanks, Tim. Those pointing fingers are indeed attached to tattooed arms!

Definitely why, even though in the Navy in Vietnam, I never got a tat because I didn’t want to be a “marked man.”

Alfred, I remember when there was a longstanding bias against all tattoos. Now that tattoos are wildly popular, they have become a very convenient pretext for prosecuting Latinos, so I see the wisdom of your hesitation.

Again Ruben you have

shown the Hypocrisy of this administration.

Their interpretation

of Brown tattoos and White tattoos. Thank you Ruben for for showing us the light even though its been overwhelming for a long time.

You are very welcome, Gaspar. These are important things to consider in our historical moment.