In Parallel Myths at David Shelton Gallery in Houston, images of Jesus, boats, nature, men (both clothed and nude), and a cryptic balcony scene conjure the narrative the exhibition title promises. Among drawings and paintings by Michael Bise, Joey Fauerso, Keith Mayerson, and Vincent Valdez, what stands out for me was Valdez’s The Strangest Fruit (2014), a suite of five drawings presented as one piece in which San Antonio-based Valdez ostensibly attempts to vocalize the largely overshadowed history of the lynching of Mexicans following the 1848 signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

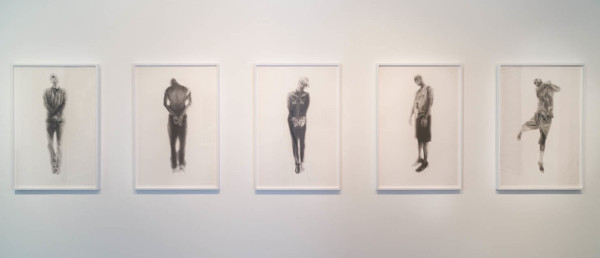

Vincent Valdez, The Strangest Fruit, Suite of five drawings, 2014, graphite on paper, each 40×26 in.

The title The Strangest Fruit is pulled directly from the poem “Strange Fruit,” written by Abel Meeropol in the 1930’s and later adopted into a song by Billie Holiday in 1939. It was a poem written in protest of the lynching of African Americans in the South, but Valdez has adopted it here for his own purposes, attaching it to images of five contemporary Chicano men being hanged.

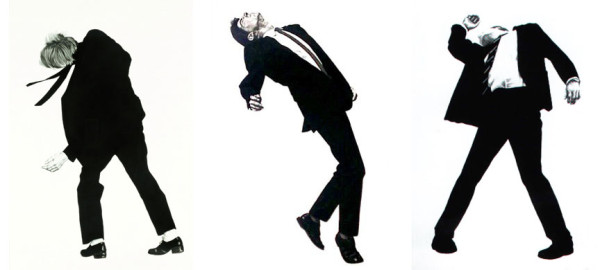

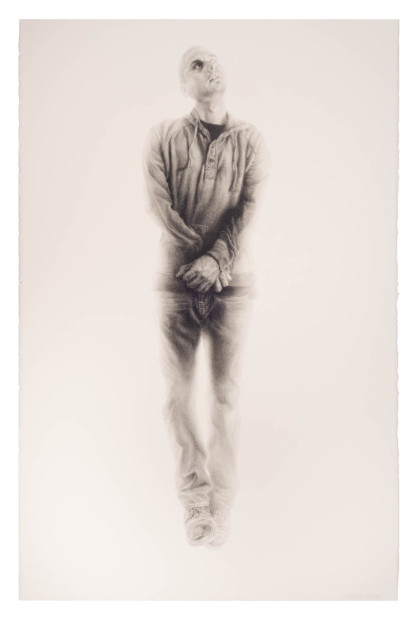

Much like Robert Longo’s Men in the Cities series (1979-1982), Valdez’s men are devoid of context. Seemingly caught in a vacuum, each man is positioned in the dead center of a stark white background, vacant of weapons and perpetrators.

Robert Longo, from the Men in the Cities series, 1979-1982

Valdez’s drawings are softer and more intricate than Longo’s, and it is this intricacy—teetering on devotional—along with a Glamour Shot-esque glow surrounding the bodies, that gives these drawings a curious patina of religiosity. Without context, the bodies are caught between gravity and ascension, and despite their morbidity, look utterly at peace, without the “bulging eyes and the twisted mouth” Meeropol’s poem mentions:

Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh!

In fact, there is no sign of struggle whatsoever, much less death. These drawings instead reflect the blessing and curse of a talented draftsman; they look exactly like what the artist saw when he drew them: not violence or pathos, but men play-acting. The close-cropping of the bodies suggests the “deaths,” if anything, came at the hands of oneself, not another individual, and certainly not a mob. Seen for themselves, Valdez’s drawings are born of fantasy and fetish, and are thus apolitical.

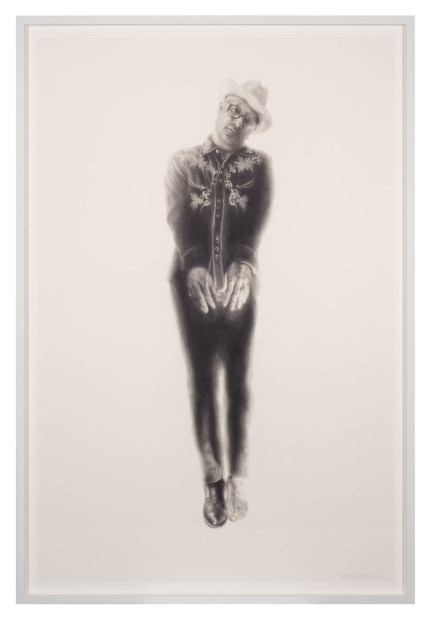

Vincent Valdez, The Strangest Fruit (4), 2014, graphite on paper, 40×26 in.

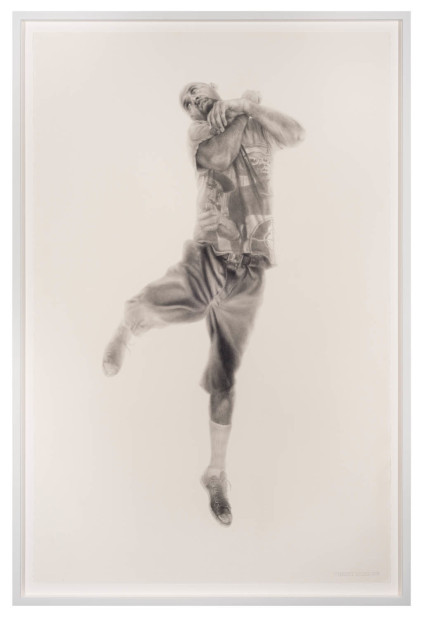

Even though the work isn’t enacting what Valdez intended, it’s still provocative. Shifting from political to personal, The Strangest Fruit instead effectively tackles questions of masculinity. At the opening, I overheard a gentleman tell his friend of The Strangest Fruit (5), “it looks like he’s dancing.” The figure’s dangling foot is probably caught on the chair he kicked out from underneath himself. Out of context, this man could plausibly be frolicking on a theater stage as much as he could be caught in the throes of death. Although the rest of the drawings are much more subdued, they nevertheless communicate this kind of theatricality with bodily gestures.

Vincent Valdez, The Strangest Fruit (5), 2014, graphite on paper, 40×26 in.

It is difficult to ignore the word “fruit” and its derogatory reference to effeminate men. While it may be true that what constitutes masculinity in our contemporary society is constantly evolving, Valdez seems to question to what extent that evolution is occurring in the Chicano community. It is also clear that, with perhaps the exception of The Strangest Fruit (2), these men are dressed as characters representing a swath of Chicano culture. Whether it be the homeboy or cowboy or anywhere in between, how bound are Chicano men to the stereotypes of machismo that are projected onto them? That perhaps they inflict upon themselves? Where is their respite? Is there any? Is it really as severe—as Valdez may be suggesting—as death?

Vincent Valdez, The Strangest Fruit (2), 2014, graphite on paper, 40×26 in.

Intended as a political work, The Strangest Fruit does not deliver, and we are all better off for it. Because if it did, it would be overly literal. But showing contemporary Chicano men in moments of complete surrender—playing out what looks like their own suicides, no less—asks truly disturbing and provocative questions regarding the limits of masculine expression within their own culture.

Hurry! The Strangest Fruit is part of Parallel Myths, running at David Shelton Gallery through July 12, 2014.