A funny thing happened on the way to the New Mexico State University Art Museum. I was heading out early to drive to Las Cruces to see Celia Álvarez Muñoz’s retrospective, Breaking the Binding, when a cat and a chicken crossed the road going opposite directions at exactly the same spot. They ignored each other, though I did witness a thought bubble rising above the kitty. “No idea” were the words it contained.

This incident was portentous in that it seemed like the kind of ordinary extraordinary moment that is good preparation for the big storytelling that Celia Álvarez Muñoz finds in small things. If stories are avenues to elsewhere, ways in, then it would be interesting to know when the first story was told in relation to when the first roads, trails, and pathways were made by humans. Did someone walk down a trail and come back to the community to tell about it? Or did someone imagine a road and talk it into existence? Which came first, the story or the road? Or was it the hunt that brought both to be? Maybe sitting down to hear a recounting of the day or making pictures of it on a cave wall were lateral moves, invented as an antidote to the sustained grind of daily activity. Or in less practical terms, humanity’s discovery of storytelling came about because it was a skill built into the body. Someone noticed their own guttural vibration accompanied by the thought, “hey, this thing makes noise,” just before gazing at the horizon and imagining everything that could happen.

We tell stories because we are stories.

Álvarez Muñoz’s photo/text vignettes and installations operate like parables — the meanings are implicit, but not obscure. They are structured like a Möbius strip, with words on one side and pictures on the other, with the twist in the strip where word-becomes-image, found in one place on the strip and then in another, illusive, with ultimate meaning held in suspense, but teasing a near conclusion that ends where it began. Her crisscrossing humor circles something else, something that resides in that part of the human brain that includes the heart. It is a kind of embrace that also holds its own with the awareness that most things have a hidden cost, what the artist calls “the undertow of comedy.”

Breaking the Binding is a journey into the experience of one person whose life is told in stories that wind through personal memory and world events. Family, folk tales, the Mexican Revolution, exposure to Catholicism, living on the border, World War II, feminism, teaching, commissions and public art, and the activism that runs parallel to and through it all find intersections in Álvarez Muñoz’s work and life and in this exhibition, which unfolds its spaces like phases in a biography with the world written on it. Born a few weeks after Amelia Earhart disappeared while trying to fly around the world, Álvarez Muñoz offers her own adventure. It is her work that gives flight.

Álvarez Muñoz got into art seriously after turning forty, an eventuality that was always there. This worked out as an advantage given all that she brought to her experiences in the MFA Program at the University of North Texas in Denton (now UNT): growing up as an only child in a close El Paso family while her father served during WWII (her sisters joined the family in 1947 and 1950), raising children, teaching elementary school art — not the background of your usual late Seventies grad student.

Growing up in close proximity to the Santa Fe International Railroad Station in downtown El Paso, it was natural that borders, tracks, rivers, and roads were the external equivalent of the movement inherent in a child’s imagination. Contrasting cultures fed her from both sides of the border, a double exposure that developed into an interwoven experience. The river itself bore witness to the Franklin Canal irrigating the upper and lower valleys, and also saw migrants drown and chains of prisoners from the county jail retrieving bodies when the canals were occasionally drained. Neighborhood swimmers sometimes drowned too, including a preschool friend of the artist. Years later, Álvarez Muñoz would develop an affinity for Weegee, the Lower East Side street photographer of the thirties and forties, known for gritty photographs of crime and traffic accidents, who gave New York the moniker Naked City.

The two sides of the family were marked by contrast, one side reverent and proper, the other bohemian and musical, both sides articulate in the extreme. These dualities and triangulations are the bones of Álvarez Muñoz’s work. The social consciousness that is integral to it first grew in response to family.

Entry to “Celia Álvarez Muñoz: Breaking the Binding” at the New Mexico State University Art Museum. Photo: Hills Snyder

Installation view of “Celia Álvarez Muñoz: Breaking the Binding” at the New Mexico State University Art Museum. Photo: Byron Fletcher

The entry wall through which you pass to gain the exhibition bears an image derived from a photo of Geronimo Hernandez (La Soldadera) on a train platform in the Buenavista station, Mexico City, in April 1912. This image became a symbol of the Mexican Revolution (1910 – 1920) at the time, and was an emblem of resistance in the seventies. In Álvarez Muñoz’s version, the look of deep concern on the face of Hernandez is replaced by a blank space, as if to suggest a tabula rasa upon which new faces of resistance may be born. The direction of the figure’s vision, as implied by her body language, points visitors to come inside where their first encounters will be with El Límite [the boundary] (1991), which unfolds in a space that features other large–scale installations, Petrocuatl (1988) and Postales [postcards] (1988).

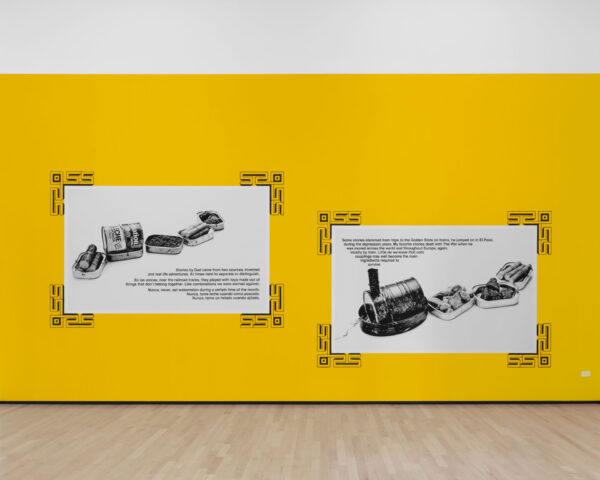

El Límite was first exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego in 1991 and is reproduced in Las Cruces as the work first encountered in the retrospective, which sets up the word/image and personal/historical dynamics that are forever features of this show and the artist’s ongoing endeavors. This piece introduces the artist’s father as a storyteller whose actual adventures were sometimes accompanied by invention, a doubling that persists in the artist’s work.

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, “El Límite,” 1991, installed at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Photo: Daniel Lang

Postales features large, airbrushed paintings of houses from border neighborhoods assimilated into the United States after the Chamizal dispute was formally settled in 1964. The dispute had origins in the 19th century when the Rio Grande River shifted its route between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, granting 600 acres of Mexican land to the United States.

The emptiness of the three lawn chairs central to the installation (pink, white, and yellow) implies a sense of community displaced. Several crossed street signs that are suspended from the ceiling further the effect, as the intersections they mark are those of Spanish words paired with phonetic versions of the same words as commonly mispronounced in English.

The paintings are based on a series of handmade postcards created by Álvarez Muñoz in the eighties and were originally made for an exhibition at the Tyler Museum of Art in Tyler, Texas. Two examples of the postcards are offered in a vitrine. One, titled Duchamp Baños, bears a message on the back: Duchamp would undoubtedly jump for joy upon seeing his theory put into practice at 4707 Maple with “wonderful water works” at the Hurera’s. An image of a house with two porch toilets converted to planters full of flowers coupled with one sentence on the back of the card simply and directly throws light onto the displacement, and simultaneously offers a commentary on the class structures, of western art history.

Installation view of “Celia Álvarez Muñoz: Breaking the Binding” at the New Mexico State University Art Museum. Photo: Byron Fletcher

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, “Petrocuatl,” 1988, installed at the New Mexico State University Art Museum. Photo: Byron Fletcher.

Petrocuatl, the central work of the exhibition, may be experienced imaginatively (if I may borrow the artist’s disguise):

Long ago, it was told that in the future the remains of a pyramid would be found in the heart of México Tenochtitlán and that a sculpture of the head of the god Petrocuatl would be found within the site.

Petrocuatl is thought to be a late addition to the pantheon of Aztec gods and is often viewed as the carrier of a prophecy of coming colonial influence, though the actual provenance of the god is not fully known. There is scant evidence suggesting a proximity to tar pits that have been dated to the mid-1500s, though proponents of the view that places the god’s origin there persist and overlook the fact that the earliest discovered physical manifestation of the god’s existence was found in the same layer of material discovered along with other items of unquestionable Pre-Columbian origin.

The Tar Pit Theory, as it has come to be called, is an attempted refutation of evidence that the god first appeared pre-Cortés, and is considered a reactionary ploy to normalize Petrocuatl as “just another god,” a kind of cousin to Quetzalcóatl. In this context he is always portrayed in glyphs as a celebrant, dancing on roller skates and pointing to the coming industrial age as the inevitability of destiny. Among those who oppose this view, he is considered to be a figure representing a mutation of the Anthropocene, his masked visage with disconnected air hose and feathered shoulders dripping oil belying his role as that of an oracle warning of a troubled future. In this view, the roller skates speak to the wheels of questionable technological progress.

Álvarez Muñoz was the first to present Petrocuatl to the public as she spoke before a graduate seminar in 1981, disguised as the professor that was actually conducting the class. In her representation, which mimed the hair, glasses, clothing, and Georgia accent of the professor, she gave a winking explanation of how her “curator husband” had made the discovery.

All this is down to Álvarez Muñoz’s grandmother Mallita, who told her when she was quite young, “This world will not go past the 21st century.” This would have been during the days when WWII gas masks were in use, when Álvarez Muñoz wore a bandana across her face during sandstorms walking to school, when, in the child’s mind, the forty skies of Lent burned like fire and the prophecy of Petrocuatl spoke directly to the future adult artist across forty years of sky and earth and family.

Petrocuatl is presented on a bifurcated wall with a large aerial photo of a section of central Mexico City on the left side. This photo came from a National Geographic spread after remains of a pyramid were found buried under the city streets in 1978. A translucent image of the pyramid is superimposed on the photo where it was thought to have been. A framed photo of the feathered gas mask, which reads as the discovered artifact, surmounts the image at the lower left corner of the pyramid. The right side of the wall, painted salmon red, serves as a foil for a large, full-body glyph of Petrocuatal, with the “21st century” story told in text below it. The work appears in this museum as if a tableau in an archaeological museum.

A gallery to the left of Petrocuatl contains staged ofrendas that were Álvarez Muñoz’s contribution to the 1991 Whitney Biennial: Ella y El [she and he] (1988) and Tú y Yo [you and I] (1989). In artspeak, these works explore “institutional tokenism,” which is itself an institutional term, effecting a kind of erasure. These works are laden with blatantly Hispanic images and objects, really weighed down with them, as if to supply some sort of gravity that held the work in place in the Biennial, which they critiqued from within.

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, “Ella y El” and “Tú y Yo,” 1988/89, installed at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Photo: Daniel Lang

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, “Ella y El,” 1988, installed at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Photo: Daniel Lang

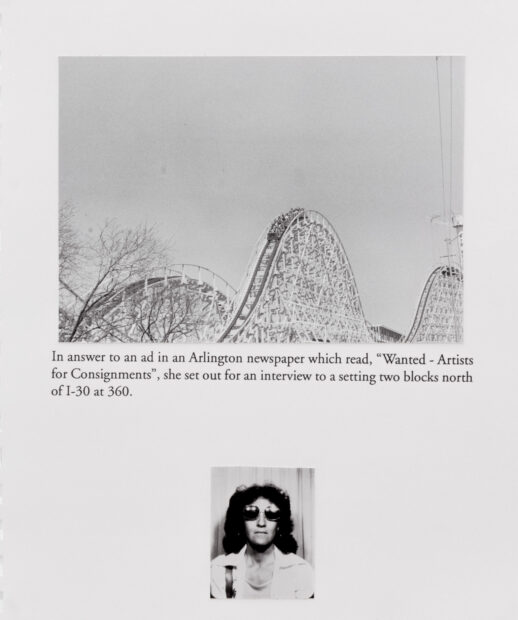

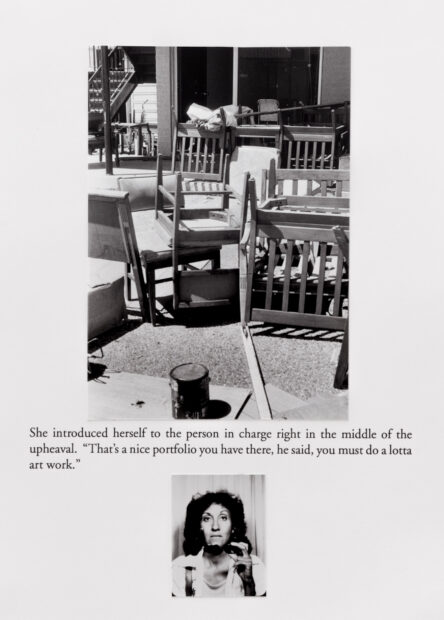

The same space offers The Scream (1980, reprinted 1992), an early work made as a graduate student in Denton. The Scream tells, in seven photos with captions, the story of the artist’s response to an ad in an Arlington newspaper. Ostensibly a search for artists for an exhibition, the situation was not as advertised and quickly veered toward chaos and unintentional hilarity, as expectations were alternately surprised, disappointed, left aghast, but never met. It is the story of a wayward curator presenting a motel remodel that was to include a space for an exhibition, an event that never happened. The experience is documented in word and image with a series of photo booth self-portraits below the texts, revealing the shifting responses of the artist as she learns more deeply how off-on-the-wrong-foot the whole project is.

As it turned out, a coffee shop in the motel replaced the curator’s ill-conceived dream of a gallery. A telling symmetry may be found between the PhD curator’s brag of the four colleges he attended and the four celebrity guests he claimed would attend the opening of the coffee shop — Vincent Price, Red Skelton, Robert Mitchum, and Kenny Rogers.

The suite of photos begins and ends with images of The Judge, a recently built wooden roller coaster next to the highway that was the artist’s route home from the motel, providing the apparent McGuffin that turns out to be the hinge in this saga of rickety experience as Álvarez Muñoz, against her better judgment, was taken for a ride.

Leaving the relatively benign disappointments of the failed motel gallery, Álvarez Muñoz’s critique of institutional power, whether in fashion, art, or the church, continues with works such as Fibra and Rompiendo la Liga.

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, “Fibra” [fibre], 1997 installed at the New Mexico State University Art Museum. Photo: Hills Snyder

In the piece, patron saints represented by santos are paired off with art patrons in an amusing equivalence — the saints may want your prayers and devotions, but art patrons may expect you to go with them to yoga or even speak in tongues. Both are preceded in the story by the paper-thin innocence of paper dolls, figures less complex.

On first approach, a towering graphic of St. Theresa clutching three lilies seems in a rush, with her elongated, windblown habit catching viewers in her wake, leading us into the tight space.

With a blank face tilted in the direction of the mock turtle from Alice in Wonderland, who is dwarfed below her, a question is posed, as if the saint is befuddled by the wonder emanating from the turtle and those of us in the same position. Perhaps she hurtles toward ecstatic bliss, as saints are wont to do, and may even lose her unwieldy habit. I suspect this is true, as the image of a naked woman testing the waters of a pond before diving in replaces the nun later on as the story progresses. The implied shedding of clothes echoes the sartorial malleability of the paper dolls which begin this account of an artist plunging nakedly forward in a world in which relationships with patronage may be murky.

The story is accompanied by a succession of projected slides of saints photographed by the artist and by text applied to the wall in a lengthy single line, which snakes its way into the deep and narrow space after enticing the viewer with the words that begin the story. The narrative turns three corners before wrapping its punchline around the edge of the cased opening that is the entrance. Though cleverly installed and made with good humor, the “we see you” challenge to those who hold power is real.

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, “Rompiendo la Liga,” 1989–90, installed at the New Mexico State University Art Museum. Photo: Byron Fletcher

Further comparative trajectories continue down a hallway outside the main space in Abriendo Tierra / Breaking Ground (1991). One wall, painted bright pink, features images of figures and animals based on Southwestern Hohokam and Mogollon cultures dating back six hundred to two thousand years. On the opposite wall, bright yellow paint supports pictographs from Alamo Canyon (east of El Paso), which span a period of four millennia. This pairing of past storytellers is juxtaposed with text describing Álvarez Muñoz’s grandparents’ journey from Jalisco, Mexico to the United States, in which the grandmother’s hope and humor is expressed in seeing the city lights of El Paso as stars that have come down to be at her same destination. The artists’ combining and retelling connects her grandparents to the deep roots of Southwestern oral and pictographic tradition. For Álvarez Muñoz the story is ongoing, and for those of us experiencing this work, walking a path between multiple timelines told in pictures and words may give rise to a sense ourselves moving incrementally, step by step, in chapters you might say, across the curve of the earth through time and space beyond the confines of the museum.

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, “Abriendo Tierra / Breaking Ground,” 1991, installed at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Photo: Philipp Scholz Ritterman

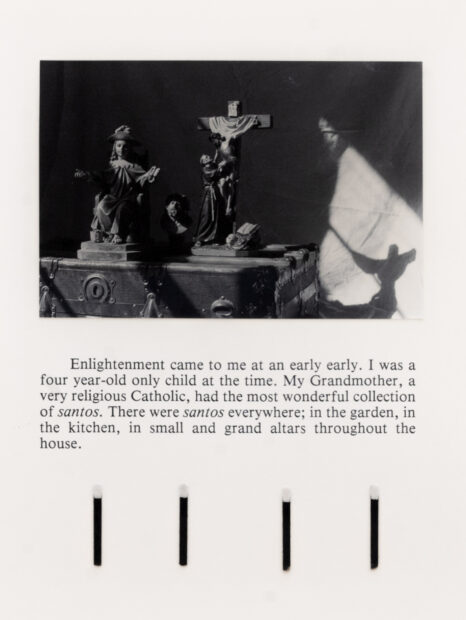

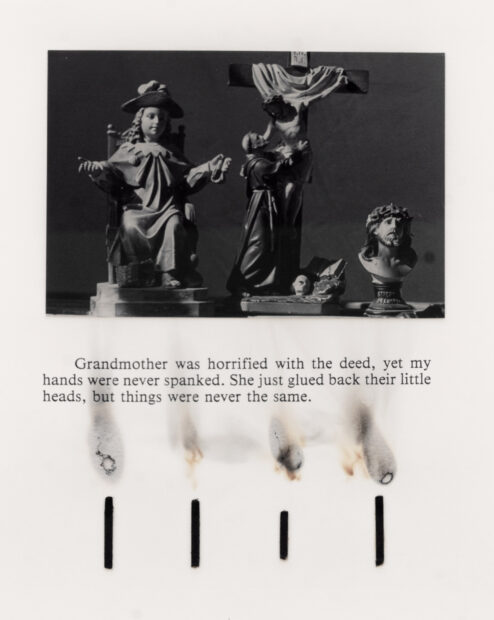

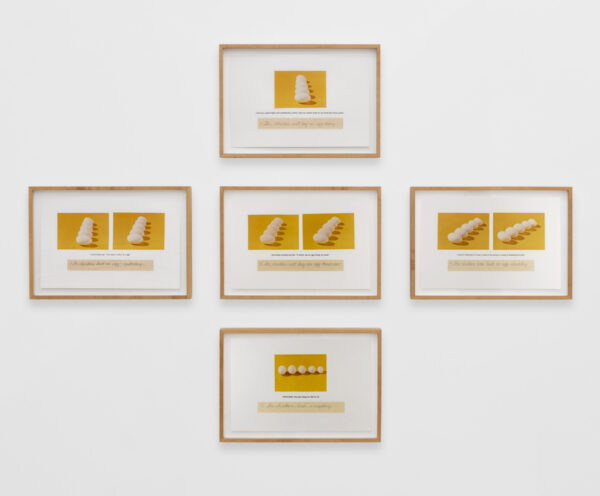

A separate space that may be entered from the hallway, chosen for its contained size and vitrine-matching wood floors, has the feel of an archive and seems perfectly made for Álvarez Muñoz’s series of ten books entitled Enlightenments, created 1980–85, and named for specific childhood memories that gradually grew into adult revelations. This room is like ground zero for the artist’s methods and concerns. The importance of this sequence of works is reflected in the well-designed catalog as the initial photo of the first Enlightenment is featured on the cover. A full half of the book in dos-à-dos binding is devoted to the series.

Celia Álvarez Muñoz, “Illuminations,” installed at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Photo: Philipp Scholz Ritterman

In Chispas Quéminme [“Sparks Burn Me”] Enlightenment #1 (1980), cardboard matches are used to mark a child’s forming skepticism and attempts at truth seeking. We are told of the child’s gut reaction to her grandmother’s collection of bultos, whose agency for heavenly help seems static in contrast to the energy of a four-year old, who decides to behead two of them. The four matches disappear one by one as the story progresses to its end, when the grandmother re-attaches the heads of the saints, though on the last page, all four matches are again present with their heads burned away. Like the glued-on heads and the singed fingers of the child’s curiosity, as knowledge is gained, nothing will ever be quite the same.

In Which Came First? Enlightenment #4 (1982), a five-part photo-diegesis, a row of five eggs is first seen end to end in descending perspective, and then, through the other photos, a progressively adjusting angle of vision across the five images ends at a view of the eggs side by side. The changing insight gathered by the viewer in consideration of the shifting photos follows the gradual revelations as experienced by grade-school-aged Álvarez Muñoz in dual pursuit of an understanding of English and chickens. These twins of inquiry are introduced in the first of five coeval captions, such as, “How does a chicken lie an egg?,” which accompany the photos. Underneath each caption, a cursive text written in pencil on a page from a Big Chief tablet conjugates the verb “lay.” The cursive counterparts are meant to be proxies for Muñoz’s work in elementary school and were made by the artist’s son, conveniently at the right age when the piece was produced. “Conveniently” is just a word of convenience, as it was perhaps her child’s arrival at that age that informed her process when conceiving the piece.One caption features a falsehood told by a teacher as a correction for the child’s misuse of the word “lie.” Álvarez Muñoz’s response to the teacher’s overly-modest fib is to hold vigil on the chickens, waiting to see eggs coming out of their mouths. Of course, the lessons of the day are that they don’t, and that authority figures may lay eggs with their attempts to shade the truth.

The five eggs seen side by side in the final photo seem to mutely offer the simultaneous mystery of likeness and variation with the simplicity of a camera merely recording what is, though the configuration of the eggs by size to mimic the perspective of the initial image alters this “truth.” The suggestion of the Uncertainty Principle is equally mute, but no less present.

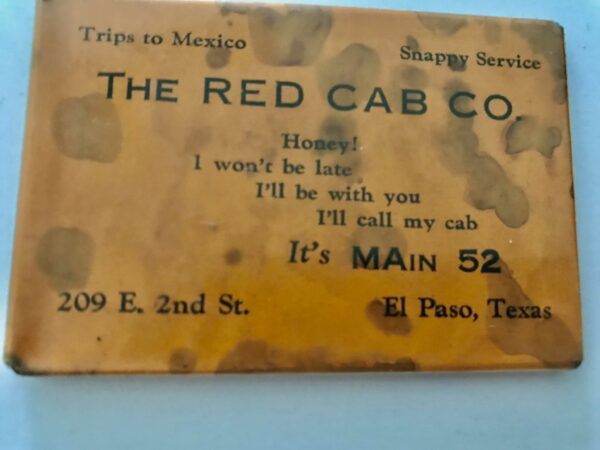

Captioning appears to run in the family, as shown by the back of a pocket mirror distributed by her uncle Severo’s El Paso taxi service. It’s practically the same font.

A taxi service pocket mirror distributed by Celia Álvarez Muñoz’s uncle’s taxi service. Photo courtesy the artist

Severo was a baby when Álvarez Muñoz’s maternal grandparents fled Mexico at the turn of the century. After settling in El Paso, their neighborhood would have a “ringside seat to the revolution.” Experiences from this time were told in family stories that the artist was exposed to as a child. They lived near a Chinese neighborhood that had begun to exist on both sides of the border in the 1880s, when Chinese workers were brought to El Paso to lay railroad tracks. Álvarez Muñoz’s grandmother told her that soldiers would knock on the door demanding to know, “Who are you for? Diaz or Madero?” and that sometimes people would answer, “Díme tu Primero” in a Chinese accent, attempting to keep the soldiers at bay.

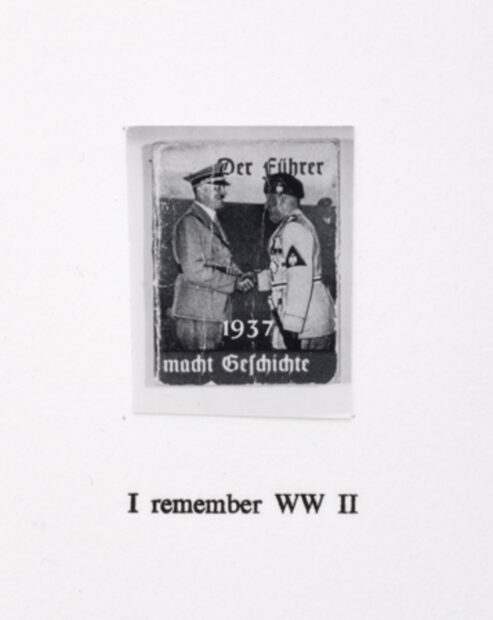

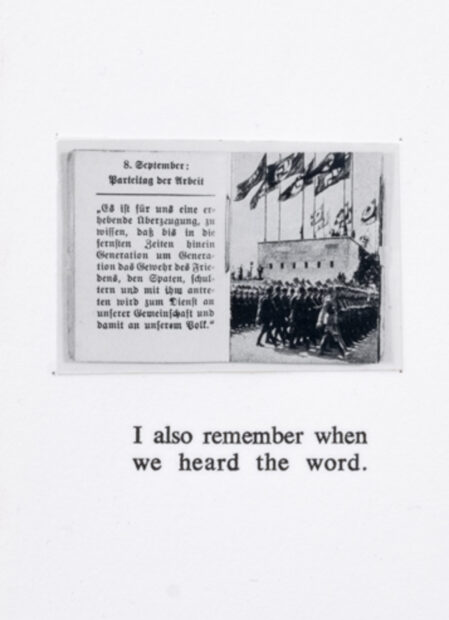

The complex mix of cultures fed Álvarez Muñoz’s imagination in tandem with all the storytelling that went on at home. She recalls listening as a family to the FDR Fireside talks, seeing war-related newsreels at the movies, and viewing photographs her father took of stray dogs he befriended during the war; the images went with the stories and printed matter he brought back. Many of the photos he sent home from Alaska, where he first served, and then from Germany, were altered, with security paint blocking out the backgrounds. The local paper featured cartoons of Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito; these graphic caricatures that accompanied her father’s photos from the war mixed together with family memories in photo albums, offering Álvarez Muñoz, who turned eight in 1945, early exposure to the art of embellishment and juxtaposition.

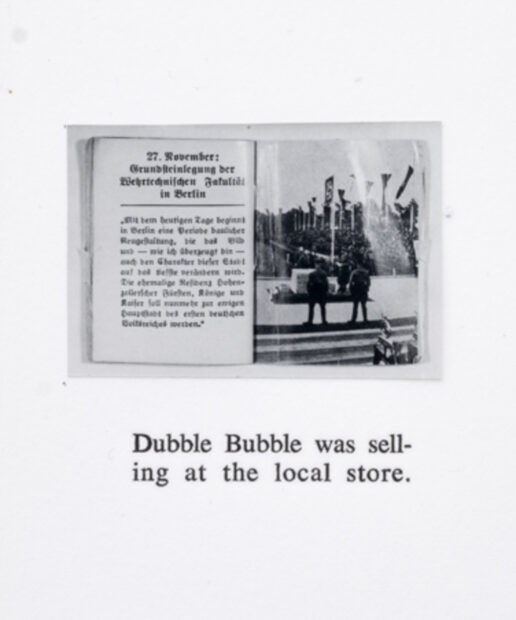

Double Bubble and WWII: Enlightenment #2 (1980-82) is a bound-in-pink suite of the eight pages of a Nazi propaganda booklet, with each page captioned by the artist. The captions are from the point of view of a kid who sees the availability of Dubble Bubble gum at the corner store as an omen of esperanza (hope). Other juxtapositions include children running to line up to buy gum described beneath a photo of Nazi soldiers heeling toe for inspection and an empty page relieved of words, representing the cloud lifting when the war ends, granting license to the children to gorge on gum.

It is true that Dubble Bubble is the best of bubble gums. It took Walter Diemer twenty years to hit upon the recipe. Likewise with Celia Álvarez Muñoz. Double Dubble and WWII: Enlightenment #2 ends with a coda:

“This little book is not a piece of propaganda. It is just a piece of experience which had been stuck on my bedpost for a number of years.”

The double-entendres circle and the tongue may seek the cheek in places, but the contemplation of pieces of bubble gum while looking at photos of Nazis doing Nazi things, imagining the lives of children during war time in El Paso, where on the trains the GIs came and went, where the daddies came home only sometimes, and imagining the lives of children in war, and imagining the worst piece, children imprisoned and tortured in war…

The artist lures us with her humor, but if it’s not a piece of this, or just a piece of that, it’s not a piece. It’s not a piece at all. It’s something else. You can hear it

“La Tempestad” [“The Tempest”] Enlightenment #10 (1985) is a pair of stories told of a grandmother who superstitiously covers mirrors and prays to the Virgin when a storm is coming and a grandfather who stuffs a clean handkerchief and a rosary in his pockets while checking himself in the mirror before stepping out after a turbulent family argument. The pairing is framed with a mirror between the texts and two staged photos from different perspectives of a stuffed squirrel grasping an acorn on a table near a window. A handkerchief is draped over the squirrel in the second photo that is correspondent with the grandfather portion of the story. If the mirror, now removed from any function of vanity, is about offering the opportunity to viewers to look closely, then the handkerchief draped over the squirrel may be about covering something up. The static squirrel may be memory, motivation, and justification solidified in narratives that may be only partially factual, while the acorn may function as the kernel of truth perceived between the then and now. The piece works like a series of elements suggesting interlocked interpretations with only the aperture of the acorn offering insight into the structural dynamics of the family.

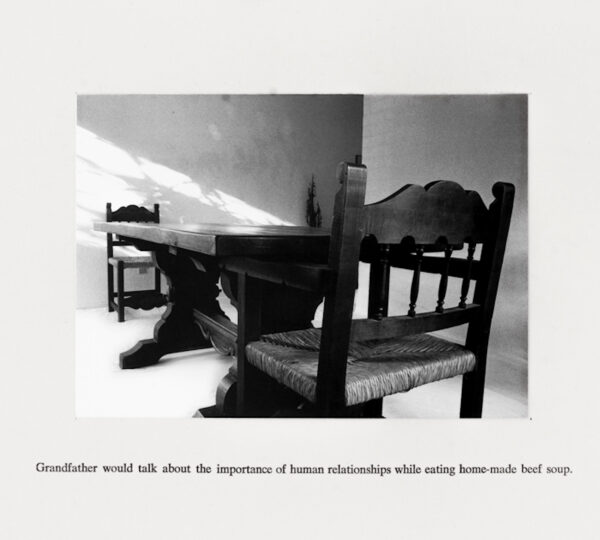

El Tuétano [“The Marrow”] Enlightenment #3 (1980 – 82) begins: “Dinnertime at grandmother’s house was always a very educational experience.” Captions tell how the grandmother is expected to slavishly meet the whims of the grandfather at the head of the table. This is metaphorically aligned with the way the patriarch disposes of a bone sucked dry. The brilliance of the piece lies in the fact that the five photos of the empty dining room are all the same, saying that the unfair dynamic delineated in the text is just business as usual, the same every day. Bone marrow is the main part of the dinner. It’s also what this work gets down to. Breaking the Binding is a pleasurable and provocative immersion into an artist’s world. It tells stories of her life and of broken boundaries extending further than any one person’s subjectivity and anything that may be conveyed here. For me, it is a double dose of seeing an old friend and knowing her much better than I had before.It’s an education.

Kate Green, Chief Curator & Nancy E. Meinig Curator of Modern & Contemporary Art at the Philbrook Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, first met Álvarez Muñoz when she was a curator at Artpace and did a studio visit with the artist in Arlington, Texas, where the artist has long lived and worked. Subsequently, when Green moved on to El Paso to serve as the El Paso Museum of Art’s Senior Curator, she delved further into Álvarez Muñoz’s work — the artist’s early prints and part of the Postales series are in the collection — and began working with her toward a project. Aware that the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego had an extensive array of Álvarez Muñoz’s work, she contacted MCASD Director, Kathryn Kanjo, for whom she had worked at Artpace, and began working toward the retrospective exhibition, which she ultimately co-curated with Isabel Casso, Associate Curator there.

Breaking the Binding remains on view at the New Mexico State University Art Museum in Las Cruces, New Mexico through March 2. Celia Álvarez Muñoz will give a keynote presentation at the museum on February 26. The retrospective will travel to Tulsa, Oklahoma for exhibition at the Philbrook Museum of Art from June 5 to August 25, 2024.

The full-color catalog, which itself breaks the binding, and is designed by Radius Books and features essays by Kate Green and Isabel Casso, with an introduction by Kathryn Kanjo. Additional texts are supplied by Josh T. Franco, Head of Collecting at the Smithsonian Museum Archive of American Art, and Álvarez Muñoz in conversation with Roberto Tejada, Hugh Royal and Lillie Cranz Cullen Distinguished Professor at the University of Houston. In October 2023, Marisa Sage, Director of NMSU Art Museum, brought the exhibition to Las Cruces.

Installation photos courtesy NMSU Art Museum. El Límite, Abriendo Tierra, Ella y El [She and He], Tú y Yo [You and I], The Scream, and Illuminations © Celia Álvarez Muñoz, from the book Celia Álvarez Muñoz: Breaking the Binding © Radius Books | Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego.