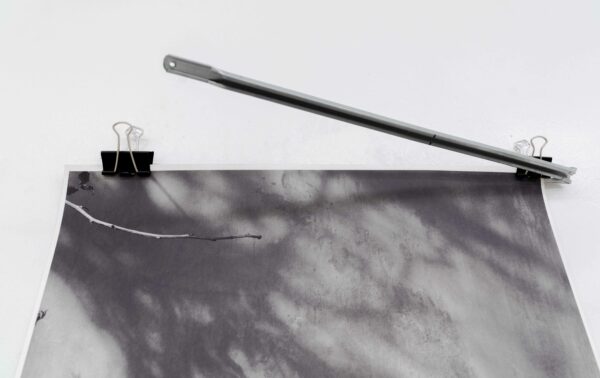

Jose Pablo Lucero “With nowhere to go,” 2022, found objects, Rives BFK black, digital print, Image courtesy of CAV Gallery.

The exhibition Cura (on view through February 18) at Cristian Anthony Vallejo Memorial Gallery in Las Cruces, New Mexico features emerging artists Maryssa Rose Chavez, from Española, New Mexico, and Jose Pablo Lucero from El Paso, Texas. Gallery owner Marcus Xavier Chormicle explained that the impetus for bringing the artists together was how each address notions of time. He added that “Chavez was making work about ancient, pre-human pasts — when this region of the country was under water — and Lucero was imagining post-human futures.” This combined body of work, about pasts and immediate futures, instills in the viewer the sense of a time-traveler, looking both to the past in search of relics and artifacts, and from the future, trying to make sense of recognizable materials made unfamiliar by time. Both artists are well versed in poetic arrangements of natural and industrial repurposed objects, which challenge framing conventions through photography, sculpture, and installation.

Installation view of “Cura” by Maryssa Rose Chavez and Jose Pablo Lucero at Cristian Anthony Vallejo Memorial Gallery (CAV) in Las Cruces, NM. Image courtesy of CAV Gallery.

The exhibition alternates between artists; it is organized like the chapters of a book, establishing a visual rhythm and conceptual dialogue between Chavez and Lucero. Both artists embrace black and white photo processes, analog and digital, which makes the transitions between their work relatively seamless. Chapter one: Lucero’s With nowhere to go (2022) begins with a print that harkens back to unexpected darkroom accidents. Could there be any other way to explain the mysterious glowing orbs emanating from leafless stems? Below the print is a black paper “screen” of sorts, both mounted to an industrial silver box. A coaxial cable makes a dramatic curve as it loops from the top back into itself at the bottom. Pincho (2022) is a photograph barely attached to an unconventional frame, a backward metal “h,” with the photo’s unattached edges curling as time passes, making the image’s content indecipherable. The glowing orb reappears as part of the composition, this time recognizable as a magnet holding the photo in place.

Installation view of “Cura” by Maryssa Rose Chavez and Jose Pablo Lucero at Cristian Anthony Vallejo Memorial Gallery (CAV) in Las Cruces, NM. Image courtesy of CAV Gallery.

How materials carry information for the narrative threads of each artist varies significantly. This difference heightens awareness and generates closer looking. For Lucero, the thread feels disrupted, non-continuous, digital. For Chavez, there is an uninterrupted, analog signal to the past through ancestry. Chapter two: Chavez’s father (2020) portrays a ghostly figure in a white tank top floating over a dramatic, cloud-filled landscape. The photo feels cropped and encased by the hand-made plaster frame, reminiscent of the plaster casts needed to stabilize broken bones, which repair and provide the time required to heal.

Maryssa Rose Chavez, “father,” 2020, Double exposure of dad at the front door overlayed with the Valles Caldera — Jemez, NM, inkjet print, foil, wood, plaster. Image courtesy of CAV Gallery.

Healing is another entry point for Cura. As Chavez stated, “art is always an attempt to cure, heal, intervene, and mend,” issues that extend beyond the personal to the familial, to the ancestral and to notions of deep time connected to the land. Family associations abound in Chavez’s “photo-sculptural showings,” many of which are situated within her grandfather’s hand-carved frames or the tin, retablo-like frame made by her “auntie Nel.” Chavez’s narrative titles —“Mom describing a Santo Box while on a drive” — provide additional access to these family photos. The time scale shifts in fountain portal (2022), a hazy image of a stone fount, remind me of a visit to ancient Mayan ruins in Palenque, Mexico. The print itself is suspended from the wall with faux pearl sewing pins and is framed by an assortment of rocks and shells, reminiscent of her grandmother’s rock collection from Chimayo, New Mexico. For Lucero, healing is a process; he addresses both injury and aggravation through his material selections and the resulting interventions, which he describes as “driven by accessibility and necessity.”

Maryssa Rose Chavez, “fountain portal,” 2020, inkjet print, shells and rocks collected in backyard. Image courtesy of CAV Gallery.

Chapter three of this exhibition consists of video works displayed in the rear of the gallery. Chavez’s Unearth (2023) plays on a monitor and shows the retrieval of a glass jar filled with liquid and dirt, her recipe for cura (treatment), which was buried in her mom’s backyard for over a year. Lucero’s installation Night interlude (2022) extends formal explorations of materiality, transforming recorded surface scratches and breaks (when viewed on a laptop), into abstracted ice flows and solar events when projected onto the wall and reflected onto the ceiling by a mirror. Lucero’s silent acts of provocation and distortion are softened by the sounds of distant dogs barking and an occasional sniffle, audio bleed from Chavez’s Unearth.

In discussing the intent of the exhibition, Chormicle commented on overarching themes of self-definition and self-actualization through art. He stated, “This show gets at something more than that. Maryssa’s work speaks to a spiritual aspect of it and Jose speaks more to the metaphysical. Being able to use material to open up the world, to assert yourself into the world, and [more specifically] the art world.” In addition to contemplating time and healing, both artists’ interrogation of framing notions challenges the borders and boundaries of the work in the gallery. How something is shown and seen can be as significant as what is represented, particularly when it guides attention or provides access to multiple perspectives. The regional framing conventions Chavez employs are recognizable, but she disrupts their familiarity. The prints are mounted on foam core and not quite to size, suspended on the wall rather than situated in the frame. For Lucero, framing is temporary, even extraneous; a process in which “both concepts and materials are in flux as a piece finds its final form.” He curls, fragments, and blocks his images and projections.

The final chapter belongs to Lucero. Derretir (2022) is a digital print of 35mm film clipped to a found metal object. The metal frame juts out across the top of the image — an adobe wall with shadows from a tree — casting a shadow of its own that mimics the only evidence in the print: a lone branch. As Chormicle expressed, “Cura is about the act of looking and showing.” As such, many of the works deserve to be seen in person: Chavez’s translucent mica sheets, an intricate shell weaving, and mounds of dirt collected from the Rio Grande; Lucero’s traces of previous use, like drill holes, electrical masking tape, and peeling paint. Although there are works in the exhibition that seem unresolved and in flux, this feels intentional. The result is work that is vulnerable and accessible, allowing us to move freely between pasts and futures. Moving freely in a region defined by borders and boundaries feels both profound and necessary.

Cura is on view through February 18 at Cristian Anthony Vallejo Memorial Gallery in Las Cruces, New Mexico.