Kate MacDowell (American, b. 1972), “Daphne,” 2007, hand built porcelain, 53 x 17 x 40 inches, collection of the artist. Photograph: artist’s website.

This article on the Apollo and Daphne myth, a regular feature in honor of Valentine’s Day, focuses on sculpture after Bernini, including relief carvings, paintings that emulate sculptures, wedding cakes, an assemblage, an abstract sculpture, and a contemporary work that places Daphne in the context of ecological destruction.

The standard account of the myth was beautifully and humorously narrated by the Roman poet Ovid in his Metamorphoses in 8 A.D. Ovid has the mighty god Apollo insult Cupid and his small bow. The latter exacts revenge by shooting two alchemical arrows, one that makes Apollo love the nymph Daphne, and one that makes Daphne despise Apollo. Apollo chases Daphne, but just as he catches up with her, she prays to her father, the river god Peneus, who saves Daphne from Apollo by transforming her into a laurel bush. Apollo then makes the laurel into a symbol of triumph.

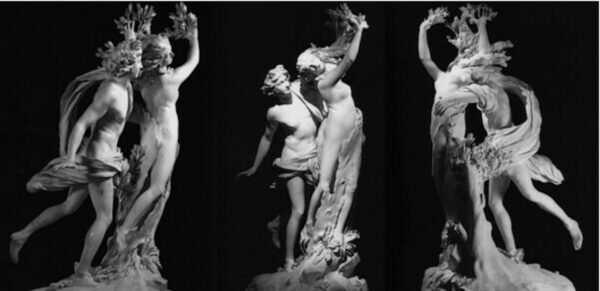

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), “Apollo and Daphne” detail of upper portion, 1622-25, marble, 95 5/8 inches (2.43 meters) high, Galleria Borghese, Rome. Photo source: Liberartemente.

Part 1 of this series, Apollo and Daphne: A Tale of Cupid’s Revenge told by Ovid and Bernini, is a deep dive into Ovid’s tale and Bernini’s masterpiece. The latter, a work of dazzling sophistication, invention, and technical mastery, is one of the defining sculptures of the Baroque era and a monument of world culture. Part 1 also includes treatments of the motif by Piero del Pollaiuolo, Schiavone, Peter Paul Rubens, Francesco Albani, Cecco Bravo, René-Antoine Houasse, François Boucher, Nicolas Poussin, Charles Meynier, and Louis Gabriel Blanchet.

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), “Apollo and Daphne,” detail of upper portion, 1908, oil on canvas, 57 x 44 inches, private collection. Photo: allartpainting / Wikimedia Commons.

“Cupid’s Revenge, Part 2,” which can be accessed here, ranges from antiquity to airbrushed fantasy. It treats Gandharan stone plates, ancient frescoes and mosaics from various sites, an ancient glass ewer, and a Byzantine ivory relief and a shawl from Egypt. It also discusses pre-Ovidian literary sources that are reflected in art, as well as illuminated manuscripts. It includes paintings by Bernardino Luini, Dosso Dossi, Théodore Chassériau, John William Waterhouse, Alexandre Benois, Meret Oppenheim, Milet Andrejevic, and Boris Vallejo. Other works include an ivory statuette by Jakob Auer, a Dutch tile, a coin by Salvador Dalí, and a queer illustration of the myth by Ivan Bubentcov.

“Cupid’s Revenge, Part 3,” which can be accessed here, commences in the Renaissance with illuminations of Christine de Pizan’s L’Epistre d’Othea. It also features a medallion by the Master of the Orpheus Legend, a pair of paintings by Pontormo, drawings by Abraham Bloemaert and Jacob Pynas, a design for a fountain by Charles Le Brun, paintings by Luca Giordano and Giambattista Tiepolo, Renaissance and Baroque jewels, several examples of Italian majolica (and one from France), and an English perfume bottle. Modern works include a Gobelin tapestry design, a Charles Rennie Mackintosh design, a Wilhelm List drawing, a Joel Peter Witkin photograph, a cake, several contemporary tattoos, and contemporary fingertip jewelry by Heather Roblin.

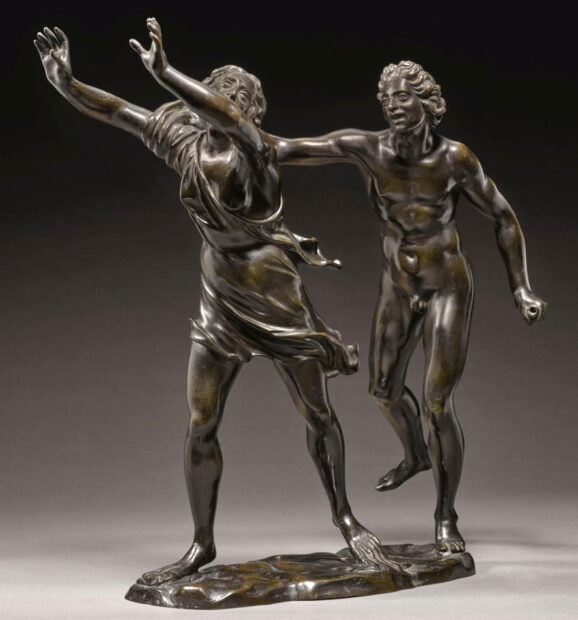

Peter Flötner (1490-1546; active 1522–1546), “Apollo and Daphne,” bronze, private collection. Photograph: Bridgeman Images.

Before we move on to post-Bernini examples of the Apollo and Daphne motif, let us first consider this example by Peter Flötner. As he noted on a print executed in the 1530s, the Swiss Renaissance sculptor and engraver prided himself on his ability to create works in both the “Italian” and “German” styles. Flötner’s Daphne leans forward a bit, but in comparison to Bernini’s dynamic sculpture, the former’s figures (and his Apollo in particular) are resoundingly static. Apollo’s astonishment is adeptly characterized, but Flötner has no inclination to put him in motion. Were we not familiar with the Ovidian version of the myth, we would have no inkling that Apollo had desperately chased Daphne, wooing her all the way.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, “Apollo and Daphne,” 1622-25, marble, 95 5/8 inches (2.43 meters) high, Galleria Borghese, Rome, triple view. Photo: kyluc.vn WorldKings.org.

Bernini, by contrast, is a veritable engineer of dynamic motion, as is evident in this triple view of his statue, which features flying limbs, drapery, and hair. Many post-Bernini sculptures and paintings of the Apollo and Daphne motif respond to Bernini’s example by emulating it in one way or another. As we shall also see, however, some artists, even if they had made faithful copies of Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne, make great efforts to break away from his influence in order to create their own, highly original treatments of this myth.

François Lespingola (French, 1644-1705) (attributed to), “Apollo and Daphne,” c. 1700, bronze on wood base, 17 1/4 (high) x 10 1/2 (wide) x 9 inches (deep); pedestal height 4 1/2 inches, width 15 1/4 inches; sold at Sotheby’s in 2010. Photograph: Sotheby’s.

As I noted in Part 1, Bernini could have introduced the figure of Peneus into his Apollo and Daphne (as he did Cerberus in his Pluto and Proserpina), but the clarity and drama of his sculpture would have suffered. Lespingola created an innovative statuette with three figures, designed to be seen in the round. Due to its small scale, it could easily be rotated by hand to appreciate various viewpoints.

The introduction of Peneus into the center of the composition greatly complicates it. Daphne hops over Peneus like a hurdle (perhaps symbolizing that she has reached the safety of her father’s terrain), and, if Apollo were to continue to chase her, the god would have to follow suit. The viewpoint provided by the above reproduction gives the best sense of the narrative. Due to the complexity of the composition, other viewpoints provide much less information about the action taking place.

François Lespingola (French, 1644-1705) (attributed to), “Apollo and Daphne,” c. 1700, bronze on wood base, 43.8 (high) x 28.4 (deep) x 39.8 cm (wide), Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden. Photograph: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden.

From the viewpoint afforded by the cast in Dresden, we can see that Apollo bends forward dramatically in order to grab Daphne’s blooming hand. They are directly above the body of Peneus, who, like a typical river god, reclines on the ground.

The Dresden museum attributes the statuette to both Lespingola and Antoine Coysevox (1640-1720). While Coysevox or Giovanni Battista Foggini (1652-1725) had traditionally been credited with creating this model, recent scholarship has favored Lespingola. See the entry in the 2010 Sotheby’s catalog.

Cast from a model attributed to François Lespingola (French, 1644-1705), “Apollo and Daphne,” first half of 18th century, bronze on wood base, 18 inches high, sold at Christie’s in 2016. Photograph: Artnet.

This view of the sculpture affords a good look at Peneus, but we only see Apollo from the back, and he almost completely blocks out Daphne.

The Christie’s auction catalog notes that the present cast closely resembles the example in Dresden, and that minor variations and departures from it could be attributed to the fact that casting had taken place at different foundries.

François Lespingola (French, 1644-1705) (attributed to), “Apollo and Daphne,” c. 1700, bronze on wood base, 17 1/4 (high) x 10 1/2 (wide) x 9 inches (deep); pedestal height 4 1/2 inches, width 15 1/4 inches; sold at Sotheby’s in 2010. Photograph: Sotheby’s.

The above view provides a great deal of information about Apollo and Daphne, though the precise location of various body parts (such as the left legs of both standing figures) is still open to question. Grasping the whole requires the spectator to rotate Lespingola’s three-figure statuette, or to move around it.

Ferdinando Tacca (Italian, 1619-1686) (attributed to), “Apollo and Daphne,” c. 1640-1650; bronze, on a later marble base, bronze: 44 by 44.5cm (17¼ by 17½ inches); base: 9 x 31cm. (3½ by 12¼ inches,) sold at Sotheby’s in 2018. Photograph: Alain R. Truong.

In its simplicity, the small bronze by Ferdinando Tacca is the antithesis of Lespingola’s three figure sculpture. In fact, since Apollo’s bow is broken off, the subject matter would be mysterious to most viewers.

Ferdinando Tacca (Italian, 1619-1686) (attributed to), “Apollo and Daphne,” c. 1640-1650, sold at Sotheby’s in 2018. Photograph: Alain R. Truong.

Tacca has given us the barest of essentials — perhaps even less than that — just a naked man chasing a barely clothed woman.

Ferdinando Tacca (Italian, 1619-1686) (attributed to), “Apollo and Daphne” (detail), c. 1640-1650, sold at Sotheby’s in 2018. Photograph: Alain R. Truong.

According to the Sotheby’s catalog entry, which (along with photographs) is reproduced by Truong, the only previously known cast is in the Louvre. The latter can be traced to Louis XIV, and is presumed to be a prime version, since Apollo has a scabbard, Daphne’s hands grow laurel leaves, and it bears an inscription with a title. Apparently, only the deluxe royal edition carries with it the bare essentials of the story.

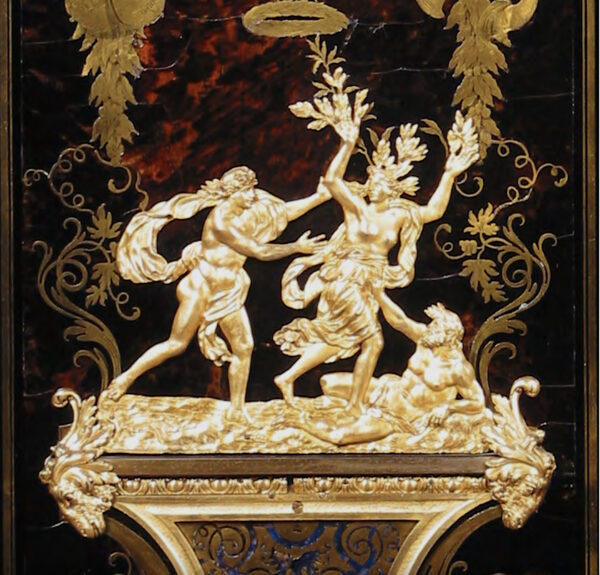

André-Charles Boulle (French 1642 – 1732) (attributed to), Wardrobe, c. 1700, oak, première-and contre-partie Boulle marquetry of brass and turtle-shell, marquetry (inside doors) of ebony, amaranth and pewter, gilt bronze, steel locks, hinges and key, 255 x 162.7 x 61 cm, the Wallace Collection, London. Photograph: Wallace Collection.

Primarily display pieces, wardrobe cabinets such as this one also had shelves that could be used for storage. The center of each door is decorated with a large gilt-bronze mount. Apollo and Daphne are depicted on the left, and Apollo Supervising the Flaying of Marsyas is on the right. Both myths were treated in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Boulle was an obsessive collector and hoarder of art works, which caused him perpetual financial difficulties. He likely also had a serious interest in metamorphosis. A 1720 workshop fire in the Louvre tragically destroyed Boulle’s art collection, which numbered thousands of works. (Click here for a French language inventory of the artworks lost in the fire.) These, according to the scholarship of the day, included a series of Metamorphoses drawings by Raphael, which were among the 48 Raphael drawings said to have been destroyed in this fire.

André-Charles Boulle (French 1642 – 1732) (attributed to), gilt bronze mount on Wardrobe door, c. 1700, the Wallace Collection, London. Photograph: Wallace Collection.

As we can see in this detail, Apollo has caught up with Daphne. But Daphne has already reached the protective dominion of her father Peneus, the water god. Her right foot appears to be under his left leg, and he touches her abdomen with his right hand, arresting her motion. This contact appears to bring about her dramatic transformation. For comparison, see the print by Schiavone in Part 1, in which Daphne takes root while standing directly on her father’s body.

In the Boulle mount, Apollo grasps — or is about to grasp — Daphne’s right arm. Daphne turns her head back at Apollo while laurel leaves and branches spring dramatically from her head and hands.

I was surprised by how robustly the male figures’ muscles are defined in this mount. Boulle wanted to become a fine artist rather than a furniture maker, and that interest shows in the details of his mounts, which are miniature tableaus.

Massimiliano Soldani (Italian, 1656–1740), “Apollo and Daphne,” c. 1700, terracotta, 55.5 x 34.2 x 21.9 cm (21 7/8 x 13 7/16 x 8 5/8 in.), Cleveland Museum of Art. Photograph: Cleveland Museum of Art.

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s website argues that Soldani “based this work on a large-scale marble sculpture from 1622–25 by the Roman artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini.” Though the qualities of Bernini’s masterpiece would have been indelibly imprinted in every Italian Baroque sculptor’s memory, the differences between the two sculptures are at least as important as any of the characteristics they have in common. In this work, Soldani self-consciously differentiated himself from Bernini’s example.

As in Bernini’s great sculpture, a tree trunk is encasing Soldani’s Daphne. However, neither her hair nor her hands are turning into laurel leaves and branches, and her only visible foot is not growing roots. Whereas Bernini created an open work with an emphasis on movement, dynamism, and transformation, Soldani has crowded his composition through the addition of three putti and a number of other three-dimensional objects, and by the act of bringing the two principal figures closer together. He has compressed the composition to such a degree that it is a veritable thicket of gesticulating arms, flowing hair, branches, and drapery.

Consequently, the compacted elements seem more like the product of a train wreck than two figures engaged in a high-speed chase. Bernini created a large-scale work that one would normally view from several angles, beginning with the rear as one entered the room (one side was originally against a wall). The full power of the narrative would be disclosed gradually, through the revelation of individual, precociously sculpted portions of the whole, though the right front view would always be the preferred view. Soldani’s small-scale work presupposed that the viewer would be familiar with Bernini’s exemplary statue, and the subject matter of his statuette was intended to be understood instantaneously.

Soldani’s Apollo grasps Daphne’s right arm. But he is no longer running. Instead, one of his feet is perched on a tree branch, which a putto also grasps. Apollo’s chest touches Daphne’s back, his stomach almost abuts her derrière, his left knee contacts her thigh, his left foot nearly touches her calf, and their heads are very close indeed. They are so unified that Daphne’s left arm could almost read as Apollo’s right arm. Curiously, for someone seeking to desperately escape her pursuer, Daphne’s torso is bent backwards, towards the very god she flees. She seems to bend away from the tree trunk that mysteriously envelops her, only to find herself situated between a veritable rock and a hard place.

Massimiliano Soldani (Italian, 1656–1740), “Apollo and Daphne” (rear view). Photograph: Cleveland Museum of Art.

From the rear, Daphne’s head appears to be cradled by Apollo’s right arm. From this perspective, she is clearly more imprisoned by the tree than is evident from the frontal view of Soldani’s statuette. One can also readily perceive the architecture of wood and stone that Soldani has crafted for the benefit of his twisting bodies.

Massimiliano Soldani (Italian, 1656–1740), “Apollo and Daphne” (detail of upper portion of statue). Photograph: Cleveland Museum of Art.

Physically, Daphne’s and Apollo’s faces are highly reminiscent of Bernini’s. Psychologically, Daphne is feeling the metamorphosis she is undergoing. The smitten Apollo, by contrast, grasps her arm while completely failing to comprehend the situation at hand. His field of vision does not enable him to recognize the changes that are taking place. He is too close (and on the wrong side of Daphne) to see what the viewer of the sculpture comprehends at once.

Massimiliano Soldani (Italian, 1656–1740), “Apollo and Daphne” (detail of center of statue). Photograph: Cleveland Museum of Art.

Two of the putti, on the other hand, have a front-row view of Daphne’s transformation into a tree. She is not experiencing the prototypical, gradual metamorphosis that one typically finds in depictions of this theme, from the ancient world to the present. Instead, it appears that Daphne is being swallowed whole by a tree, the way Jonah was swallowed by the whale. Moreover, the putti grasp curved layers of the encasing tree trunk that (from a frontal angle) suggest bows, the very weapon Apollo mocked Cupid for utilizing, and the very weapon Cupid turned on Apollo in order to take his revenge.

Soldani made this composition in several mediums, including bronze (an example that was photographed is now lost) and white porcelain. In October of 1716, Soldani, in a letter to Giovanni Giacomo Zamboni, his London-based agent, noted that Lord Burlington had ordered eight works, including an Apollo and Daphne (the most expensive of the lot), which the artist described as “a still richer group. It represents Apollo embracing Daphne, who is changing into a laurel tree, with three playing putti, who make the group yet richer and more harmonious, and other details which finish the composition off….” In a 1717 letter to Zamboni, Soldani says his Apollo and Daphne is “fit for a king,” so he clearly had a high opinion of it. See AlainTruong.com

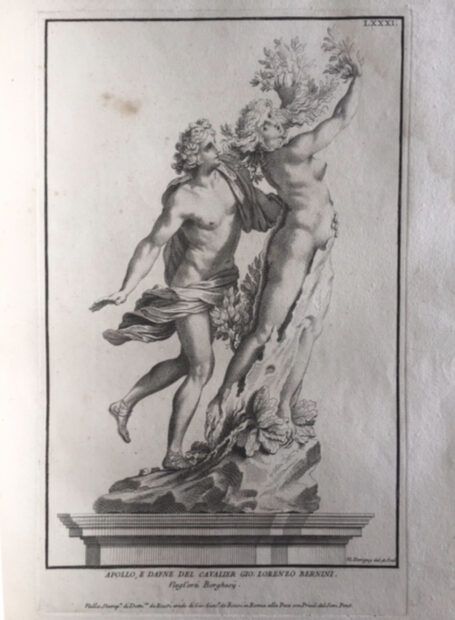

Louis Dorigny (French, 1654-1742), “Apollo and Daphne by Gianlorenzo Bernini,” 1693, engraving. Photograph: Victoria and Albert Museum.

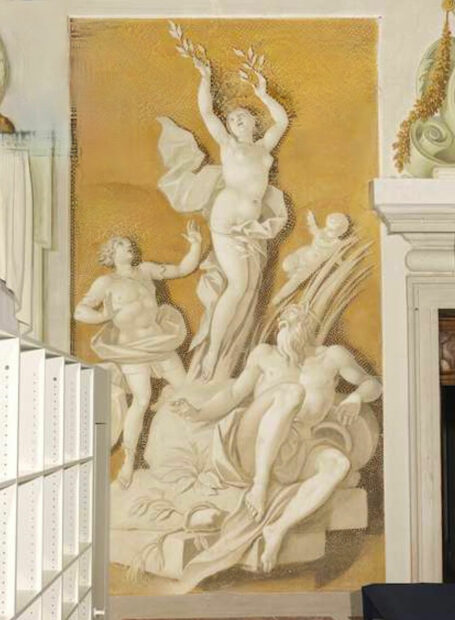

Louis Dorigny had made a very faithful engraving of Bernini’s statue in 1693. (Importantly, it documents the original base on which it rested.) Thus he was very well acquainted with Bernini’s version when he made a trompe l’oeil, faux marble fresco a few years later in 1709.

Louis Dorigny, “Apollo and Daphne,” 1709, fresco, Villa Manin, Room of Flora, Passariano, Italy. Photograph: Mauro Magliani.

Dorigny’s monochrome fresco on a gold background features patterns of white spheres, anticipating a device utilized by the Surrealist Salvador Dalí more than two centuries later. Dorigny brings together all four principal protagonists: Daphne rises up in the middle like the centerpiece of a fountain. (See Le Brun’s fountain design copied in a print in Part 3.) Apollo arrives a little too late to catch Daphne. Instead, his outstretched arms gesture with astonishment at what he sees: leaves are germinating from Daphne’s hands.

Louis Dorigny, “Apollo and Daphne” (detail of Daphne), 1709, fresco, Villa Manin, Room of Flora, Passariano, Italy. Photograph: Mauro Magliani.

Apollo cannot yet perceive that a tree trunk is encasing Daphne, and that tiny roots are shooting from the toes on her right foot into the hard rock beneath her. Balancing Apollo, Cupid flies in from the right side to get a closer look. A fluttering piece of drapery decorously shields her genitals, held in place by twigs emanating from the hollow trunk.

Louis Dorigny, “Apollo and Daphne” (detail of center), 1709, fresco, Villa Manin, Room of Flora, Passariano, Italy. Photograph: Mauro Magliani.

Peneus, Daphne’s river god father, is seated in the foreground. His flowing robes tumble down the step-like base, taking on the function of the water that should be spilling from his overturned jug. He turns his head as if he is just registering Daphne’s metamorphosis, though he is the very agent of her transformation. In comparison to other depictions of this myth in which Peneus makes an appearance, he seems nonchalant and distanced, as though he were an incidental observer, rather than a central participant in this high drama.

The cumulative effect of Dorigny’s composition is to elevate Daphne and to heighten her presence. Rather than a mere innocent nymph who is successively victimized by Cupid and Apollo, only to be turned into a foreign object by her father, Daphne is posed like a Venus on a summit, or like the subject of a dramatic and magnificent apotheosis.

Guillaume and Nicolas Coustou, Daphne Pursued by Apollo (“Daphne” by Guillaume Coustou, “Apollo” by Nicolas Coustou) c. 1713-1714, marble, Cour Marly, Louvre Museum. Photograph: Louvre Museum.

Now in the Cour Marly at the Louvre, each of these sculptures was originally situated in an ornamental pond in the park of Louis XIV’s chateau (now destroyed) at Marly, c. 1714. The Coustou brothers created individual statues of Apollo and Daphne, which have individual characteristics and are individually signed.

Seeking to capture the dynamism and the sense of movement in Bernini’s example — or perhaps even to attempt to outdo him in some aspects — the brothers depicted their figures in full flight. In order to permit the bodies to lean forward as far as they do (Guillaume’s Daphne almost looks like she is diving), and to simultaneously elevate one leg to create this illusion of great motion, each statue requires a fictive stump to provide additional support.

Nicolas studied in Paris with his famous sculptor uncle, Charles Antoine Coysevox, who headed the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. When he was 23, Nicolas won the Prix de Rome (then known as the Colbert Prize), which enabled him to study at the French Academy in Rome. He and his brother subsequently worked with Coysevox at Versailles and Marly.

Since the Apollo and Daphne statues were originally placed at a considerable distance from one another, they would have represented an early stage of the chase. During the French Revolution, many of Nicolas’ statues were destroyed. The Apollo and Daphne (along with other surviving statues from Marly) were subsequently installed in the Tuileries Gardens from 1798 to 1940. See EU Touring for photographs of cast reproductions in the Tuileries, situated where the original statues had been located.

After Nicolas Coustou, cast of “Apollo,” originally c. 1713-1714, Tuilleries Garden, Paris. Photograph: EU Touring.

As is evident in the above photograph, from some angles it appears as though Nicolas’ figure of Apollo is impaled on the stump designed to help support his weight. Guillaume’s figure of Daphne also doesn’t fare very well from some angles, either. Clearly, the Coustou brothers were unable to disguise their supporting struts as effectively as Bernini. In this endeavor, Bernini had the advantage of utilizing a multi-figural group wherein Daphne is directed upward (see discussion in Part 1). The Coustou brothers created independent sculptures that powerfully capture the sense of the desperate footrace that ensued between the two protagonists of this myth, but it came at the expense of a certain awkwardness.

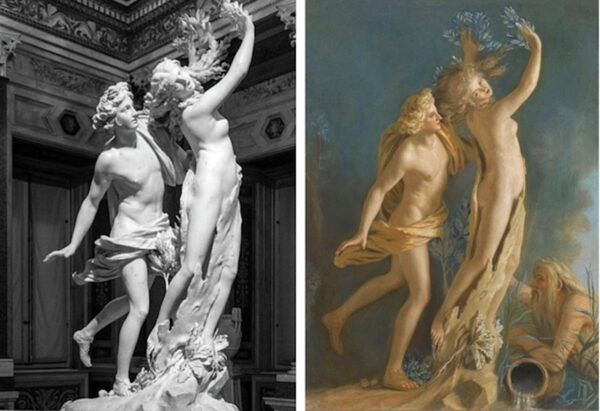

Left: Bernini, “Apollo and Daphne”; Right: Jean-Etienne Liotard (Swiss, 1702-1789), “Apollo and Daphne, after Lorenzo Bernini’s Marble Group in the Galleria Borghese, Rome,” 1736, pastel on paper, 66.2 cm. high x 51.2 cm. wide, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Photograph: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Jean-Etienne Liotard’s copy of Bernini’s famous statue has a very soft touch in comparison to surfaces in some of Liotard’s other pastels. For me, at least, the background color evokes an underwater context, endowing the pastel with a dream-like atmosphere. Perhaps it was a way of implicitly situating the action in the realm of the water god Peneus.

The faces of Liotard’s Apollo and Daphne are much less expressive than those in Bernini’s sculpture. Liotard gives us much less detail, especially in the hair and in the textures of the wood and rocks. Whereas painters and pastel artists can often convey more detail than sculptors, here Liotard makes no attempt to compete with Bernini in terms of vivid details and textures.

Liotard has added a figure of Peneus, who leans forward among the reeds. His left forearm rests on his flowing water jug, and his right arm is extended to halt Apollo’s advance.

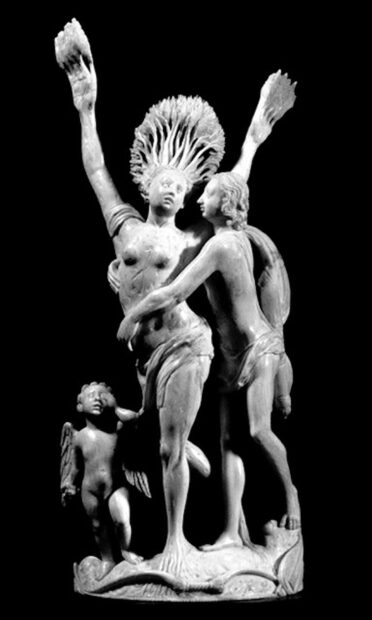

Jean Antoine Belleteste (French, 1731–1811), “Apollo and Daphne,” c. 1780, ivory, height 18 cm., Dieppe, Musée du Château. Photograph: AKG Images.

Jean Belleteste’s charming and eccentric ivory statuette returns to a static composition that is typical of pre-Baroque exemplars. Daphne looks rather larger and more physically powerful than Apollo (her legs, especially), who resembles a slight and skinny medieval lad, rather than the mighty classical god. Whereas Bernini based the head of his Apollo on that of the formidable Apollo Belvedere, with its noble Roman nose, Belleteste’s has a sloping forehead, a pointy nose, and a declining chin, such that, when seen in profile, the point of its nose forms a “v” shape. Belleteste’s Daphne has the appearance of someone who could crack Apollo’s non-classical skull between her mighty thighs.

As Apollo’s arms encircle Daphne’s torso, he thinks that he has her at last. Like many figures of Apollo (in painting and sculpture) who touch Daphne, or who come into close proximity to her, he is oblivious to her ongoing transformation. It’s a “the closer he is, the less he knows” paradox.

Jean Antoine Belleteste (French, 1731–1811), “Apollo and Daphne” (detail of upper section), c. 1780. Photograph: AKG Images.

Daphne’s head bursts into a headdress-like coiffure worthy of a Vegas showgirl, though it is made up of complex and meticulously groomed branches and small leaves that would make a bonsai gardener envious. Her upraised hands are like well-choreographed paddles, with fingers turning into tiny branches that give rise to well-ordered leaves.

Jean Antoine Belleteste (French, 1731–1811), “Apollo and Daphne” (detail of lower section), c. 1780. Photograph: AKG Images.

Her left foot, which rests on the earth, erupts into a system of parallel roots. Roots also spring from her elevated right foot. Oddly enough, Apollo’s legs mirror those of Daphne (though different legs are planted and upraised), and Apollo’s downward pointing toes echo the rooting toes on Daphne’s left foot.

Cupid, for his part, rests his hand on his cheek, presumably in wonder at the events his arrows have set in motion. Apollo’s mighty bow lies on the ground, a symbol of the godly hunter’s defeat by Cupid’s tiny bow, which lies above it.

Bertel Thorvaldsen (Danish, 1770-1844), “Apollo and Daphne,” presumably 1838, cast plaster, 24.5 cm high, 22.5 cm wide, Thorwaldsen Museum, Copenhagen. Photograph: Thorwaldsen Museum.

The Danish neoclassical sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen created a relief in which Apollo prepares to serenade Daphne with his lyre, (Compare this to Dosso Dossi’s version in Part 2) while the latter is encased in a tree. Peneus is properly seated on a chair-like ledge, rapt in Homeric contemplation, as water pours from his upturned vase. Cupid, acting innocent and leaning against the tree, places a quizzical finger on his chin. Apollo’s weight is borne on his right leg, while his left foot is raised and placed on the base of the tree trunk. His head is garlanded with laurel leaves, and he is in the act of placing a garland on his lyre, which is why the instrument rests on his thigh.

Bertel Thorvaldsen (Danish, 1770-1844), “Apollo and Daphne” (detail), presumably 1838, cast plaster, 24.5 cm high, 22.5 cm wide, Thorwaldsen Museum, Copenhagen. Photograph: Thorwaldsen Museum.

In this detail of the upper section of the relief, Daphne’s body is clearly demarcated in profile. The swell of her stomach is above Cupid’s head, and her right breast is just to the right of Apollo’s left hand. Her arms are raised and extended backward. Daphne’s head, above the lyre and behind her right arm, gazes out towards the viewer of the relief. The leaves behind Apollo’s head function as Daphne’s hair. When we look at the lower portion of the trunk, we can also see a hint of Daphne’s legs and feet. Apollo is straddling them with his left ankle and foot. Thus Daphne is palpably and anthropomorphically present — at the very least as a fantasy or hallucination on the part of the sad, smitten god.

For comparison images of Daphne anthropomorphically encased in a tree, see Bernardino Luini and Salvador Dalí in Part 2.

Our next sculptor, Arno Breker, requires an introduction. He was Hitler’s favorite sculptor. Breker is pictured below guiding Hitler and Speer through Paris after the Nazi occupation in 1940. Breker had moved to Paris in 1927, and he returned to Germany in 1934. He subsequently joined the Nazi Party and was named “official state sculptor.”

Albert Speer (left), Adolf Hitler (center), and Arno Breker, June 23,1940. Photograph: United States National Archives and Records Administration

In 1944, Breker was one of 378 Gottbegnadeten (divinely gifted) artists that Joseph Goebbels made exempt from military duty. Breker specialized in monumental nude figures, which he produced for the 1936 Olympic Games and for the entrance to Speer’s New Reich Chancellery in Berlin. The latter included Die Party (two torch bearers) and The Wehrmacht (sword bearers).

This over-life-sized relief features the “heroic” nudes that were the artist’s specialty — though his figures were usually considerably more bombastic and muscle-bound. They were inspired by the most ripped Hellenistic sculptures, and by Michelangelo. Readiness, for instance, closely follows Michelangelo’s David, but instead of a graceful image of power in repose, Breker created a twisting torso with a contorted face. Breker’s ever-ready Aryan giant is either very angry or extremely constipated. He’s prepared for battle with a big sword, but with no clothes or armor. He’d better hope that his muscles are even more metallic than they appear to be. Breker’s females are softer, with upper torsos that seem inflated, rather than defined by a sharply muscled surface.

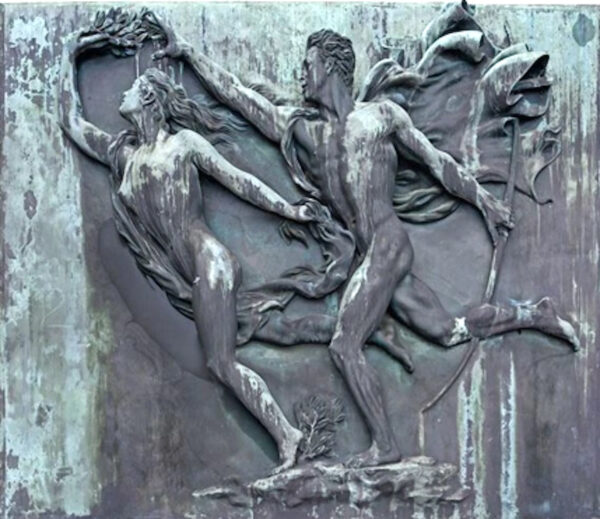

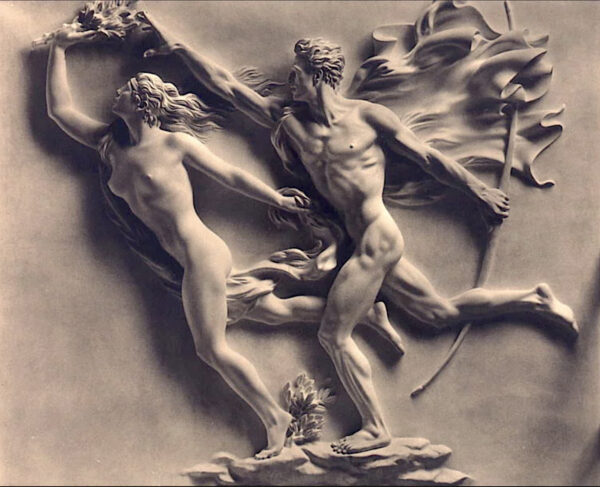

Arno Breker (German, 1900-1991), “Apollo and Daphne,” 1940-42, bronze, 240 x 285 x 40 cm, one of two bronze casts, private collection. Photo: Mutual Art.

In Breker’s Apollo and Daphne, the figure of Apollo has a huge chest-to-waist ratio that is comparable to that of Michelangelo’s David. Though he tries to render a graceful image of flight-like motion, Breker’s figures are stiff and unduly repetitious. In particular, the upraised arms of the two figures short-circuit the sense of forward motion. The shortcomings of Breker’s relief give me a better appreciation of the Coustou brothers’ Apollo and Daphne.

Arno Breker (German, 1900-1991), “Apollo and Daphne,” c. 1940-42, plaster model (?), 240 x 285 x 40 cm, Photograph: unidentified vintage photograph.

Strangely, in a barely modified Nazi salute, Apollo reaches towards Daphne’s right hand, the most distant part of her body. Upon close examination, she holds — rather than sprouts — a sprig of laurels.

Arno Breker (German, 1900-1991), “Apollo and Daphne” (detail of upper left section), c. 1940-42, plaster model (?), 240 x 285 x 40 cm. Photograph: unidentified vintage photograph.

As an expression of Nazi will, the theme of Apollo and Daphne doesn’t make much narrative sense, since it is essentially a myth in which the great male god is frustrated and defeated. Moreover, according to Ovid, Apollo is forever mournful and he forever obsesses on his loss. This is why he elevates the laurel to a symbol of victory. But in Breker’s relief, Daphne does not metamorphose into a laurel. If we look down at the rock outcropping from which her left foot springs, we can see that laurel grows out of that rock, rather than from her foot. The Aryan conqueror, longbow in hand, one-ups the Apollo of antiquity. For he can apparently have his nymph and her laurels, too.

By implication, Peneus, in these circumstances, can will the laurel bush into existence, but he cannot transform his daughter into a laurel and thereby save her from the rapacious hunter’s advance.

Perhaps Apollo’s gesture is meant to symbolize the Nazis reaching for the laurels of history. Apollo snatches them, seizing a time-honored symbol for the glory of Hitler’s would-be thousand-year Reich. The national Nazi emblem was a laurel wreath-sheathed swastika with an eagle perched atop it.

Edgar Britton (American, 1901-1982), “Apollo and Daphne,” c. 1970, polished bronze, private collection. Photograph: Denver Post.

Edgar Britton was an artist whose career had two distinct phases. In the first part, influenced by realist traditions, including Grant Wood (who he had studied with at the University of Iowa) and Mexican Muralism, Britton painted many murals in the midwest region, including some for the WPA. After he moved to Colorado in 1942 for health reasons (a diagnosis of tuberculosis), he was primarily a sculptor. See Chicagomodern.org. and The Annex Galleries.

Britton’s Apollo and Daphne features two torsos with truncated limbs. The figure of Daphne, attached to the rear of Apollo via a truncated leg, rises up, with her truncated arms flung behind her, and her left leg kicked up high. Apollo, meanwhile, leans to the right, with his left arm outstretched and his right leg extended outward. Britton’s figures are balletic: they seem more like a pair of ice skaters or ballet dancers than runners. One can envision them gliding across a rink or stage, with the female flying through the air. Britton’s Apollo and Daphne is more kinetically balletic than a related sculpture that explicitly depicts a ballet: Ballet Rescue, c. 1971.

Britton’s Apollo and Daphne beautifully expresses grace and gravity defying motion, though it doesn’t, on its own, transmit much information about the narrative, not even the fact that Daphne is desperately eluding Apollo. But if the viewer comes to Britton’s sculpture with knowledge of the myth, and with knowledge of the history of its representation in art, one can readily appreciate Daphne’s physically elevated position as part of a long continuum of this subject. Through his abstract concision, Britton makes a beautiful, streamlined, fully modern contribution to this theme.

Arman (Armand Fernandez), (French-American, 1928 – 2005), “À Marienbad,” 1987, 86 inches high (sculpture only); 99 inches high including attached plinth, x 38 inches wide, cast photographed in Greenwich, CT prior to 2015 sale. Photograph: Live Auctioneers.

Arman, who is best known as a Dada and Surrealism-influenced assemblage and deconstruction artist, has reproduced Bernini’s figural group in bronze, and he has deconstructed them by breaking them up into shallow bronze slivers with relief-like flatness. He partially reconstructs them by integrating them with similarly deconstructed stringed instruments (the latter are among the artist’s favorite motifs). This angle taken in the above illustration features the closest reference to Bernini’s sculptural prototype.

Arman (Armand Fernandez), (French-American, 1928 – 2005), “À Marienbad,” 1987, 86 inches high (sculpture only), 99 inches high including attached plinth, x 38 inches wide, cast photographed in Greenwich, CT prior to 2015 sale. Photograph: Live Auctioneers.

From this rear angle, the most legible detail that can be connected to Bernini’s sculpture is Apollo’s grasping hand, which futilely takes hold of Daphne’s transforming torso.

Arman (Armand Fernandez), (French-American, 1928 – 2005), “À Marienbad,” 1987, 86 inches high (sculpture only), 99 inches high including attached plinth, x 38 inches wide, cast photographed in Greenwich, CT prior to 2015 sale. Photograph: Invaluable.

This detail shows how disassembled and broken-up the work really is, which can only be fully appreciated from close proximity. From a distance, one reads the work as a more solid construction.

Jackie Shaffer, “Bernini Inspired Apollo and Daphne Wedding Cake,” modeling chocolate, royal icing, gum paste, edible glue. Photograph: Cake Central blog.

Jackie Schaffer had intended to create an Apollo and Daphne cake for several years before she made the example pictured above. She was inspired by Victorian wedding cakes that had pronounced architectural components. See the Cake Central blog for a print and a photograph of two of these historic cakes, alongside one of Schaffer’s sketches for her Apollo and Daphne cake. In order to fashion the architectural ornaments, Schaffer created silicon molds. A miniature version of Bernini’s great statue tops her cake.

Since the myth concludes with love’s eternal frustration, rather than its consummation and happy perpetuation, it is an odd subject for a wedding cake, albeit, in this case, a very beautiful one.

Jackie Shaffer, “Bernini Inspired Apollo and Daphne Wedding Cake” (detail of central tier), modeling chocolate, royal icing, gum paste, edible glue. Photograph: Cake Central blog.

In the central tier, Shaffer has placed Cupid within a niche and framed him with Solomonic columns (in an apparent nod to Bernini’s Baldacchino). Shaffer has flanked Cupid with independent busts of Apollo and Daphne, which resemble portrait busts from antiquity. The Apollo bust appears to be eyeing the Daphne bust, whereas the latter has downcast eyes and does not reciprocate. Appropriately enough, in their human form, thanks to Cupid’s machinations, the two remain forever separate. Thus Shaffer acknowledges Cupid as the prime mover and ultimate victor of this tale, for it is his mischievous vengeance that sets Daphne’s metamorphosis into motion.

Kate MacDowell (American, b. 1972), “Daphne,” 2007, hand built porcelain, 53 x 17 x 40 inches, private collection. Photograph: artist’s website.

In her artist’s statement, MacDowell reflects on the conflict between the “romantic ideal of union with the natural world” and “our contemporary impact on the environment.” Her work is in part a response to environmental stressors, notably “climate change, toxic pollution, and g[enetically] m[odified] crops.” MacDowell’s sculptures often draw on cultural touchstones.

MacDowell utilizes porcelain as a medium because she is drawn to “its luminous and ghostly qualities.” She also values its strength and its ability to convey fine textures. Paradoxically, porcelain reflects “the impermanence and fragility of natural forms in a dying ecosystem,” and, nonetheless, “can last for thousands of years and is historically associated with high status and value.”

Kate MacDowell (American, b. 1972), “Daphne,” 2007, hand built porcelain, 53 x 17 x 40 inches, private collection. Photograph: artist’s website.

When Daphne was displayed at the Museum of Arts and Design’s exhibition Body & Soul: New International Ceramics in 2013-2014, the label noted that the work was partially a response to coming across areas of clearcut forests while backpacking in Washington and Oregon. MacDowell points out that in the ancient myth Daphne was transformed “from woman to tree.” In MacDowell’s installation, Daphne is further transformed into a “clearcut slash pile,” which the artist characterizes as “a different kind of ‘rape.’”

MacDowell identifies with nature, and she wants viewers of Daphne to reflect on the losses caused by environmental degradation, including the “sensory delights of texture and form [that] are removed as we allow parts of our body to be cut away.”

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has written or contributed to 19 catalogs and books. He has curated more than thirty exhibitions, and his upcoming 50-year retrospective devoted to Rolando Briseño will be on view at Centro de Artes in San Antonio from August 13, 2024 to February 9, 2025.