The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, with Dale Chihuly’s “Niijima Floats” (2017) installation. Photo: Barbara Purcell

If people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones, then the people who own Crystal Bridges shouldn’t be stoned. Regardless of how you feel about the retail giant Walmart, its heirs, the Walton family, have a stellar art collection nestled in the northwest corner of Arkansas. And they want you to come visit, free of charge.

The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art spans centuries of work and acres of leafy landscape in Bentonville, AR in the very town where Walmart is headquartered. Despite the irony of the world’s largest big-box chain exhibiting priceless art, the museum manages to exude an un-ironic cool factor. Indigenous, colonial, and contemporary works side by side, telling a story that’s more circular than linear…courtesy of the wealthiest family in America.

So how exactly did Warhols end up in Walmart? Founder Sam Walton first moved his family to Bentonville in the 1950s, opening a 5&10 on the town square. Today, that 5&10 store is a quaint museum, which is currently undergoing renovations until spring 2024. But when it reopens, it’ll no doubt continue to espouse the folksy virtues of the patriarch’s philosophy — “the kinds of traditional principles that made America great in the first place,” a phrase that jumped out at me when I first visited.

But it’s hard to get too hung up on the evils of capitalism when a scoop of ice cream at its cafe costs basically a buck. Just don’t be fooled by Bentonville’s throwback charm: the Walton Family Foundation is busy expanding in the region. Construction is well underway on an eco-friendly corporate campus, and a four-year medical school with a decidedly holistic bent is also being built. Even Crystal Bridges itself, which first opened in 2011, is getting a 100,000-square-foot add-on (the facility is currently 200,000 square feet).

Architect Moshe Safdie originally designed the museum’s “nature-centric” layout to complement the surrounding landscape, much like how a Frank Lloyd Wright house (there is one located on the premises) embraces spatial harmony. Tree-covered hills put on a quiet show across from the main pond as colorful orbs by glass master Dale Chihuly sit in the water’s still surface. Curved windows in glass corridors mimic organic contours that can be admired from every angle. The entire design is a blend of art and zen.

Across town, The Momentary — Crystal Bridges’ younger sibling (also free admission) — features work by emerging artists in a 63,000-square-foot former cheese factory. It’s anything but cheesy — the Momentary is fun. And the Waltons are clearly as comfortable with showcasing up-and-comers as they are with painters from, say, the Hudson River School. (Parts of Bentonville could pass for a Thomas Cole painting, of which there are several on view.) But you don’t need to travel back and forth between the two museums to appreciate a mix of then and now; works from different eras and different cultures have been installed in conversation with one another throughout Crystal Bridges’ collection galleries.

In the Early American Art Galleries, for example, frontier oil paintings are presented with mid-nineteenth century Iroquois, Lakota, and Ojibwe crafts. Down the way, an illuminated glass travel trunk by Wisconsin-based artist Beth Lipman titled Belonging(s) (2020) references an oil painting circa 1735 of Abigail Levy Franks — installed on the wall just behind it. Franks, who was born into a prominent family in London, later moved to New York and mingled in high society with her husband Jacob. Lipman’s glass installation, filled with trinkets and objects, directly connects to the nearly 300-year-old painting in a way that feels refreshing and new.

Of course museums have been reorganizing their collections for some time now; Crystal Bridges completed their own overhaul in 2018. But this particular experiment — a contemporary artist responding to a colonial work, from a few feet away — engages in a kind of curatorial time travel that reflects the high turbidity of human history.

Installation view in the Early American Galleries of Beth Lipman’s “Belonging(s),” 2020, glass, ceramic, gold lacquer, enamel paint, salt, sand, and adhesive, 27 in. × 40 1/2 in. × 23 in. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas. Photo: Ironside Photography.

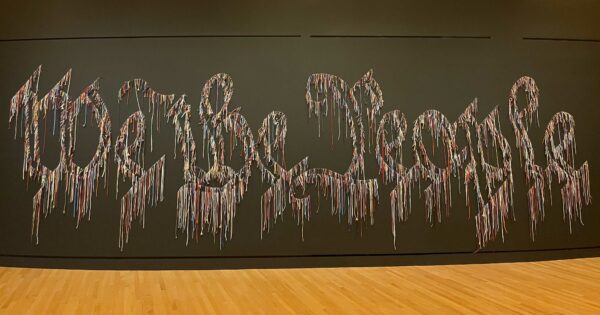

Perhaps the most striking example is right at the entrance of the galleries: Nari Ward’s 28-foot installation We the People (black version) (2015), written in the identical back-slanted calligraphy from the U.S. Constitution. The Preamble’s first three words explode across the black wall, made up of thousands of multicolored shoelaces collected by Ward around New York City. It is a youthful, energetic take on the signatory of democracy, constructed out of something every American can appreciate: a good pair of kicks.

Other highlights in the permanent collection: Louise Bourgeois’ towering Maman spider, Robert Indiana’s iconic LOVE sculpture, a Yayoi Kusama infinity room. Not to mention accompanying wall text throughout the galleries attempting to untangle some difficult knots: slavery, colonialism, capitalism, corporatism.

Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Room—My Heart is Dancing into the Universe (2018) at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Photo: Barbara Purcell.

It may seem like there should be a built-in punchline here — Walmart versus high art — but it’s no joke. Crystal Bridges is in a class of its own.

A previous version of this article appeared in the now-defunct Austin-based publication Sightlines. For more information about Crystal Bridges, go here.

3 comments

Totally agree with everything you wrote. The museum was beautiful and gracious. Especially loved their incorporation of art/sound/light into the outdoor forest – a don’t miss!

Crystal Bridges – eighth wonder in the world? It really is a special place, as diverse as Wal-Mart’s customers.

Most of our major US museum collections come from the fortunes of capitalists and robber barons. We have no monarchs, dictators and popes to scoop up all the treasures for themselves. Schlock and fine art intermingle. I just read the article about how Gagosian got his start in The New Yorker by selling posters on the street. Alice Walton, who was initially looked on with art world snobbery when she started the collection, has made something beautiful that even non-Walmart shoppers enjoy.