This is the first in a series of interviews talking with the collaborative team leading artist Vicki Meek’s Urban Historical Reclamation and Recognition project in Dallas’ Tenth Street Historic District Freedman’s Town neighborhood in Oak Cliff. The project is sponsored by the Nasher Sculpture Center.

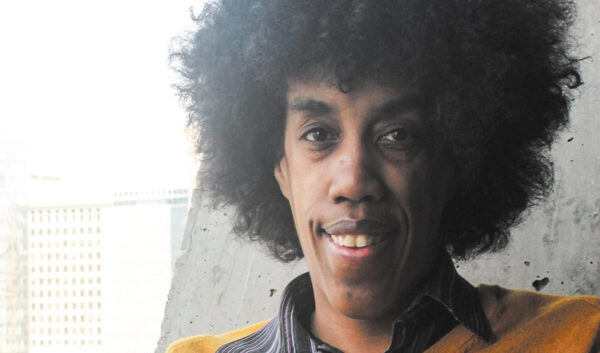

Earlier this year, I invited playwright Jonathan Norton to join me via Zoom to discuss his practice, his work at Dallas Theater Center, and his involvement in the Nasher Public: Urban Historical Reclamation and Recognition (UHRR) Project.

Conceived and led by artist Vicki Meek, the multi-disciplinary, socially engaged art project has a truly diverse team of creative individuals that includes Norton, Christian Vazquez (a filmmaker), Angel Faz (a social practice visual artist), and Dr. Marvin Dulaney (a historian). Together, they will document and memorialize the Tenth Street Historic District Freedman’s Town in Oak Cliff.

But first, who is Jonathan Norton?! We must know…

Carris Adams (CA): Years ago, when I was fresh out of grad school and unsure of this art thing, I decided that I would stay engaged in the arts through writing, among other things. Artists invent ways to stay engaged in the arts, if not through our studios.

Glasstire has asked me to interview the team of the Urban Historical Reclamation and Recognition Project (UHRR). First I interviewed artist Vicki Meek, and she told me, “You absolutely have to speak to Jonathan next.”

My first question, before we get into the work of UHRR, what are you working on right now? Where are you in your residency at the Dallas Theater Center (DTC)?

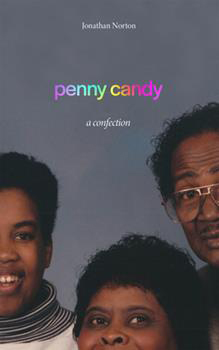

JN: My relationship with DTC as playwright-in-residence started back in the spring of 2019 as a part-time position after the previous P-i-R, my mentor Will Power, took a position at Spelman College. Later that summer, DTC produced my play, Penny Candy. In the fall of 2021, the theater was able to make my residency full-time.

Now, I am responsible for writing a play every season. I’m either in a development mode or production mode for my plays. I also assist with season planning as the literary manager, which involves reading a lot of plays, managing the script submission process, and supporting our new play development efforts. I also support our Public Works department through leading playwriting workshops with our community partners.

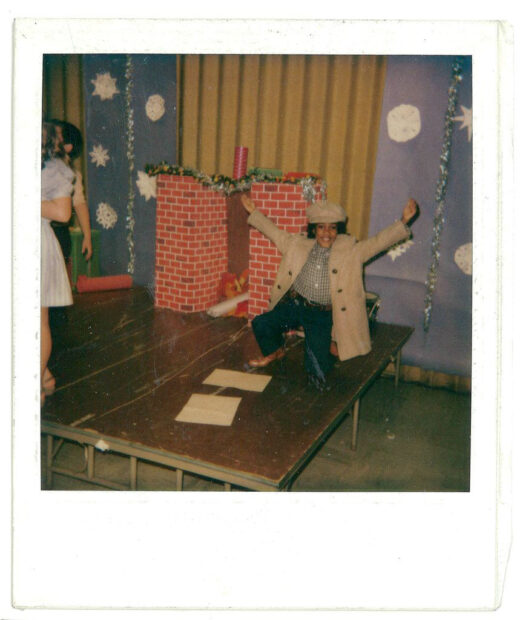

CA: You recently completed a series of workshops at the Janie C. Turner Recreation Center. You grew up going to that rec center. How does it feel, returning to a place or places that influenced you in your youth?

JN: Every now and then, I have moments where something feels smaller. When I was younger, these spaces felt large, and now they feel smaller as I am older. So that was weird. [Laughs.] But seriously, it feels great to reconnect with Janie C.Turner and the memories that are associated with that place. And it’s great being able to give back in that way.

Also, growing up, my parents had a candy house. So being there also brought back memories of the candy house in an indirect way.

CA: Ahhhh. This is where penny candy comes from.

JN: Yes! We sold chips, candy, sodas. My dad would barbecue. He would also make nachos, frito pies, and snow cones. It was a huge operation. This is where I get my entrepreneurial spirit.

CA: Does the entrepreneurial spirit inspire you to make your ideas come to fruition or to seek out multiple ways of working?

JN: Both!

CA: I think people underestimate moments like that. I once lived with family members that had candy trucks. They also had a grill in one of the trucks and they would park at apartment complexes or outside a club on a Friday or Saturday night.

JN: We had a candy truck too! I remember that sometimes we would have competition. A new candy house would open and my mom would send me there to spy. I would report back to my parents and say things like, “I give them two weeks, tops!”

The candy house gave me a sense of pride in how serious my parents took their work, how professional they were and the care that they put into making the living room of our apartment a candy store. They took it very seriously. This influenced me to take my work seriously, have an eye for progress, planning, development, and to have goals.

CA: I’m always excited by the drive that creatives have to put an idea out into the world. When you can pull from a variety of resources it creates a kind of depth. This brings me to your work and a review of a play titled Six Days on the Road. The reviewer said that you “forged characters with depth that defy cliches.” How do you accomplish this?

JN: Largely for me, I try not to plan too much. I try not to think too far ahead of myself. Both the cliche and the formulaic come from being too in control of the process. What defies that is the element of surprise, and you have to be able to surprise yourself.

So in terms of surprise, I like to imagine my characters as real people. I assume that there is a lot I don’t know about them. I also assume that there’s a lot they are not yet willing to share with me. For instance, if you were to meet someone for the first time, or even just a casual acquaintance, and they tell you their entire life’s story and all of their TMI trauma, that is a red flag! Run! Therefore, it’s fine that I don’t know very much about my characters in the beginning. I simply take what little I know of these characters and fashion a first draft of the play.

After I’ve completed the first draft — and with each new draft — this helps the characters to trust me more. And often there’s things the characters do that don’t make sense or don’t seem to be in their best interest. But as I earn their trust, they reveal the true reasons for their actions. The more time and rigor I invest in the play, the more they trust me, and the more secrets they are willing to reveal.

CA: I asked Vicki this and now I will ask you: Do you believe that there are a series of ancestors that are making the work through you, in addition to your lived experience?

JN: Yes, I call it blood memory. There are things that are embedded deep in our DNA and history that get passed on, generation to generation. From person to person, without any biological connection.

CA: Blood memory is a great term. It makes me think of epigenetics, but blood is a very direct and clear term to use.

JN: One of the ways it shows up is when you have anxiety or fear around random things that you shouldn’t. Or that you don’t have the lived experience to be bothered by it — but you’re deeply unsettled by the thing and you don’t know where that came from. That is blood memory.

CA: Is this how you decide what stories to investigate?

JN: Yes. I always try to write the thing that frightens me the most, or something that feels outside of my ability — that will push me. And typically the things that scare me the most always hold my attention.

CA: That’s scary! How do you move past the fear to investigate a story?

JN: It’s a learned behavior and it developed out of necessity. The majority of my early writing opportunities came through commissions, where I promised to create work based on difficult subjects like the Atlanta Child Murders. And there were always moments when I wanted to stop and change subjects, but I didn’t want to develop a reputation for starting projects and not finishing them. So I had to learn to stick with it. And I didn’t want to let the folks down — folks like Vicki Meek, Will Power, Regina Washington, and Teresa Wash who gave me those opportunities.

For instance, Vicki gave me my first commission to write a play. It was $2,500, which was the most I’d ever been paid as a writer at that time. And having that commission forced me to push through the fear, indecision, or insecurity. But also pushing past these fears helps me to deal with other personal issues I’m facing. And finally, I really appreciate that exploring dark chapters helps me to discover what’s not in the history books.

CA: Once you decide to sit with the fear, indecision, or insecurity and move forward, how does the research feed into this process? Do you dive into the research and see what you can find? Do you collect stories from your community, etc.?

JN: Research is twofold for me. One part is historical and the other is ideation. And the ideation is about what inspires me. What aesthetics are needed for the story I’m trying to tell, or what things are in the world that are already in conversation with the story. In graduate school at Southern Methodist University, I took a class with Vicki Meek and for my project I decided to write a play. I had not written a play in years, and this project got me back to writing.

First, I would identify an individual or group of African American artists of interest and study their work. Based on my exploration, I would write a play inspired by their work — but not about their work. I chose the Saar women (Betye, Alison, and Lezley). During this time I had the university search engines behind me and I found all kinds of great things about the Saars. But I also found myself inspired by the work of choreographer Robert Battle and also Sting’s music. A really odd combination of things. One thing just led to the other. But what I find difficult, and can be a trap, is trying to write the play while researching at the same time. Too much time spent researching can aid in procrastinating or an overstuffed story.

Also, since working with Vicki, I feel that playwrights are more closely aligned to visual artists than with other theater artists.

CA: Tell me more about that.

JN: Playwrights work in solitude. Eventually we get to collaborate with others. But our process starts in solitude. Similar to visual artists. And we are makers. We’re the generative artists of the theater. The other disciplines are primarily interpretive. And in many ways playwrights speak a very different language than other theater artists. I think we speak a language more closely aligned to that of visual artists. But because we spend so much time in the world of the theater and that was our training, we’ve never been able to venture out and make that discovery. So it’s kinda like being adopted and having biological family you’ve never met. Working with Vicki helped me to make that connection. I’m also adopted. So I guess it all tracks. [Laughs.]

CA: You have invested heavily in Dallas’ local theater scene through your writing and through your work at DTC. How are you continuing to shape the local theater scene?

JN: First, when helping to develop a local art scene, one must remain active and support other companies outside of DTC. And when I am outside of Dallas, I see myself as an ambassador for the Dallas arts community. The older I get, the more I do not have interest in living in New York City. I’m not against working there. But I’m not interested in living there full-time. Plus, New York doesn’t need anyone to help spread the word that the arts are important. I feel that Dallas artists still have the opportunity to develop DFW audiences and create excitement and support for the work we do.

Also, I love taking folks out to coffee to discuss their work, sharing resources and knowledge, and encouraging folks to pursue different opportunities. A lot of my work is encouraging people to go forward with the ideas they want to bring to life, or to do the thing they are scared of doing.

CA: You are working with Vicki Meek and the team for the UHRR project. Congrats on being a part of this project and on the NEA Our Town Grant you were recently awarded. My last question: What are your dreams for this project?

JN: My dream is that this project will bring awareness to the 10th Street community — its history as well as the gentrification that is happening in the area. The neighborhood hasn’t been fully gentrified yet, it is still in the beginning stages, but it is happening. My hope is that this work can have an impact on what is happening before the community is completely redeveloped.

There is so much hope and opportunity to support the people and keep the history of that community alive. They should be able to retain agency over that neighborhood and how it’s governed. Hopefully the work we can do will increase that awareness and act as a model for other communities in similar situations, whether local, statewide, or nationwide.