Nacogdoches-based artist Candace Hicks has an affinity for the written word. As a ferocious reader, Hicks encounters similar recurring events or wordings in unrelated books, makes note of these coincidences, and records them in her own hand-stitched volumes inspired by nostalgic notebooks.

Constructed out of fabric and containing Hicks’s narrative, her works can be found in both art museums and libraries across the United States, including the Boston Athenaeum, the Fine Arts Library at Harvard University, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, among others.

In addition to discussing her current teaching position, Hicks shared with me an insider’s look at her process, inspiration, and recent works.

Caleb Bell (CB): You are currently an Associate Professor of Art at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches. How long have you been there and what classes do you typically teach?

Candace Hicks (CH): I’ve been teaching here for ten years. I’ve taught lots of things, but I especially enjoy foundations. As the first class that freshmen take as they embark on their chosen discipline, I want to challenge and ignite them.

CB: Would you say that same passion is what drew you to teaching in the first place?

CH: I got into teaching because I kind of couldn’t believe that such a gig was possible. Making things with curious people and working together to solve creative problems really energizes me. I did other jobs before I taught, but I think I needed time to come to a realization that you don’t need to be an ultimate authority in order to teach effectively. I still worry all the time about whether or not my students learn the essential things they need, but that’s the downside of teaching. You never know whether you are doing a good job.

CB: Do you find it difficult to teach full time and maintain your own studio practice? How do you juggle both?

CH: Being pulled in multiple directions helps with making work. It feels like I’m stealing time to work on things, like I’m getting away with something. There’s an illicit appeal in seeing your ideas take shape when you could be doing the dishes or something quotidian. When my son was younger, I stayed up nights to work, and I only realized when it was over how unsuited I am to late hours. A fantasy would be long stretches of uninterrupted time focused in the studio, but I’ve never had that. Maybe I wouldn’t thrive without the constraints of job and family.

CB: Speaking of your own artistic practice, I wanted to discuss your ongoing Common Threads volumes. I know each book is hand-stitched and the text filling them comes from collected coincidences. Can you go into more detail about how they are created and where the text comes from?

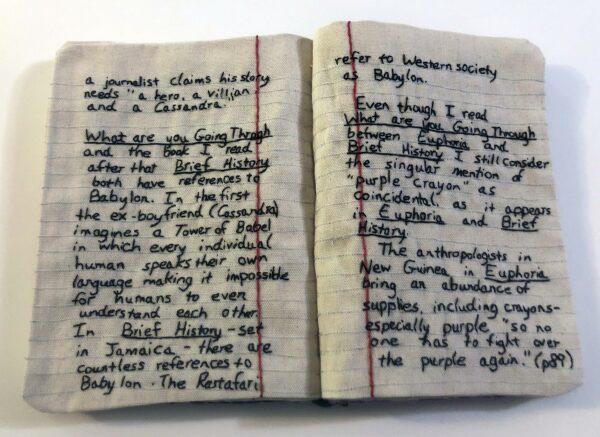

CH: I’ve been working on this series for 18 years! This week I’m stitching Volume 141, so it’s something that has held my interest for a long time. Reading books, especially fiction, is as necessary as sleeping, exercise, food and water. Some artists make work because they feel compelled, but that’s how I feel about stories. So, I read a lot, and I notice that sometimes a word, phrase, or character name appears in two or more books in a row. I find really juicy phrases like “black currant lozenge” or “antique dental instrument” in two unrelated books read in succession. Good writers of fiction know that a chance encounter or coincidence convinces the reader of the believability of a plot. We basically only tell stories of serendipity, and we suspend our disbelief when we know the coincidences have been orchestrated by the author of fiction.

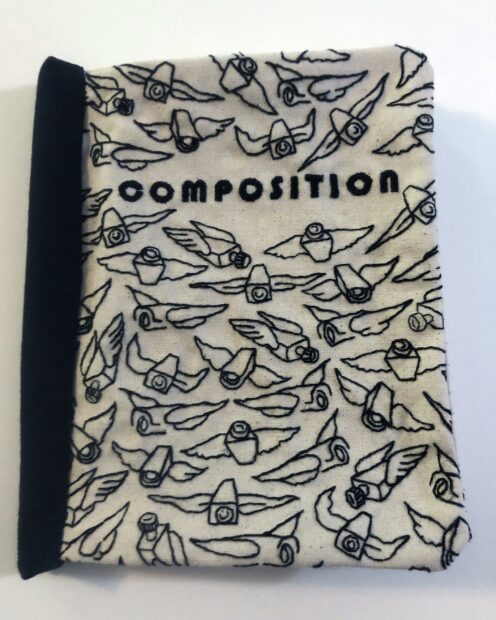

Here in the books I’m reading, another intertextual story emerges, fueled by my own random selections. No one else is reading the same books as me in the same order, so in a way, my reading is my life’s work. The hand-stitched notebooks that I make recording the coincidences I uncover are a by-product of that process. I call them Common Threads because I relish a pun. The text, cover, and illustration are all stitched in embroidery floss on fabric. Each volume is unique.

CB: How many coincidences are documented in the average volume of yours?

CH: It depends how involved they are… three to six. Each volume is only eight pages.

CB: How did you settle on their classic composition notebook design?

CH: I’ve always carried a composition notebook, preferring lined paper to a blank sketchbook. I like the form for its instant recognizability and ubiquity. The familiar and mass produced takes on a special quality when it’s made by hand.

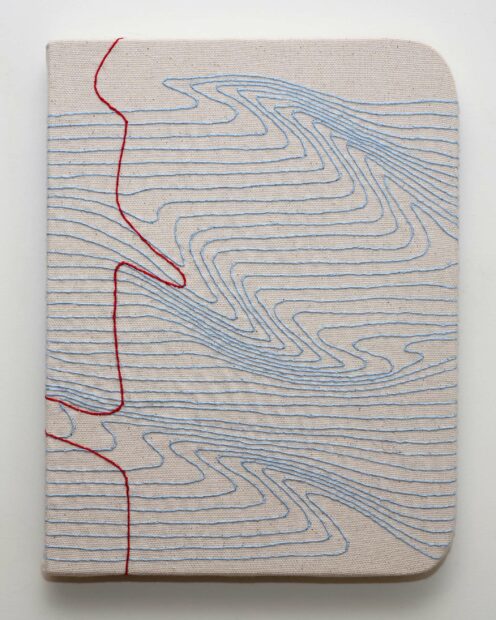

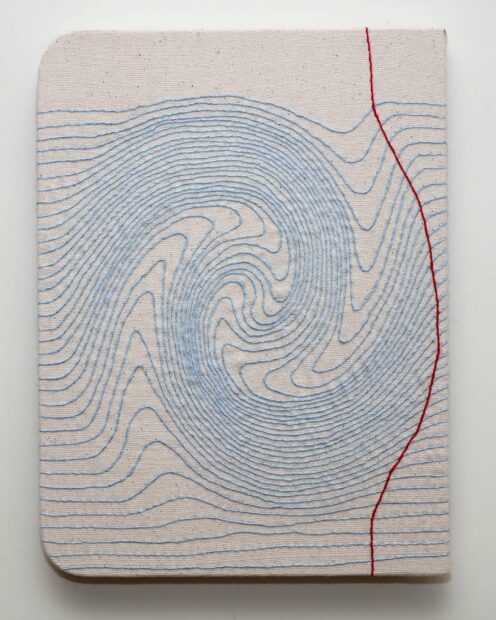

CB: I can see how all those same thoughts relate to your more recent Notes for String Theory series, where you alter the lines of the paper to create shapes and patterns. Would you care to share more about those works and how they came to be?

CH: Most all of my work is text-based. Even my interactive installations include copious text and/or accompanying books. During Covid-19 isolation, I started finding it harder to write, or even read. Playing around with a way to make a drawing of a sheet of blank paper, I discovered that I could stretch the embroidered canvas like a painting over a shaped panel. Suddenly, so many variations occurred to me. I’ve made hundreds of these drawings. They share the trompe l’oeil effect of the notebooks in that viewers sometimes do a double take, at first not placing the texture as stitching.

Previously, I made a series of large-scale artist’s books called, String Theory: Understanding Coincidence in the Multiverse, and I like to think of the Notes as precursors. Even though they come after String Theory chronologically, these distinctions don’t matter in the multiverse, and it affords me another cherished punny title. The many permutations warp the space of the picture plane in all the ways I can imagine.

CB: You are going to lead an upcoming embroidery workshop online through the Center for Book Arts in New York. Poking Fun: Sampler Embroidery will take place on Thursday, July 21. In that class, will you be sharing more about Common Threads and Notes for String Theory along with the techniques used to produce them?

CH: Yes, I will probably share some of the items I have in my studio, such as recent work. I have also designed a few patterns to distribute to the group that are more in the vein of a “sampler.” I became fascinated with the history of embroidery after reading Rozsicka Parker’s The Subversive Stitch, and I’m excited to discuss that past. I never really set out to be an embroidery artist, and I’m still quite an amateur in the craft. I only recently learned the names of some of the basic stitches that I use all the time, so that I can refer to them correctly. Also, I’ve learned some new-to-me stitches to add to my repertoire and my designs. There’s a vibrant community of practitioners of all manner of needlework, and I’m happy to be a part of that. I don’t mind being a dilettante, as one could never master all the variety of techniques that’s out there.