Installation view of Mayuko Ono Gray and Mark Greenwalt’s show, “Cohabitation.” Photo: Emily Wallace

At the end of January, Mayuko Ono Gray and Mark Greenwalt visited the Dishman Art Museum to discuss their show Cohabitation 2022, their influences, and their processes. In an interview, they graciously provided a glimpse of their life together as partners and artists.

Sarah Ridley (SR): The title of the show is Cohabitation. What does cohabitation mean to you?

Mark Greenwalt (MG): We were going through possibilities, and of course, we’re married. We refer to each other as partners because a healthy marriage has to be a partnership, but our studio practices are really quite separate. She visits me in my studio, I visit her in her studio, but we’re very independent. When it comes to the studio practice, we’re just cohabitating. We’re under one roof, but she’s mostly upstairs, and I’m downstairs.

For the longest time, I always thought that falling in love with another artist was not a good idea. Perhaps I didn’t think it was a good idea due to fear of competition, but the worst situation would be if you were living and working with another artist who you didn’t respect. However, I have tremendous respect for Mayuko’s work. Mayuko draws, but she has such a different way of doing things: she works really quickly. Although, sometimes she can be annoying with her process. I will be waking up in the morning, all groggy, and then there she is at the end of the bed with her camera for that reference photo.

SR: What gets shared outside of the studio? Do you share processes, ideas, techniques, or similar tastes?

Mayuko Ono Gray (MOG): We do have very similar tastes. It is rare that he loves something that I hate. We have respect for craft; we do not have respect for anti-craft. My favorite artist is M. C. Escher. He employs a little bit of play, and I try to keep my art lighthearted and avoid being too serious. I also enjoy the detail in Escher’s work, as well as in Albrecht Durer’s.

MG: In our work, we both gravitate toward representational art, although we are very much fans of non-representational art as well. I am a huge fan of Chris Troutman, Luis Corpus, and Vincent Valdez. I’m also a big Old Masters junkie because I’ve always been interested in the process of pulling images out of paper. The drawings of the Old Masters were often not intended to be a final work of art, so you see their animated, sketchy qualities. In Italian, this quality is called the primo pensieri or “first thoughts.” The sketches and lines are not mistakes; they often come out of the gestural drawing process.

SR: Can you tell us about your process, Mayuko?

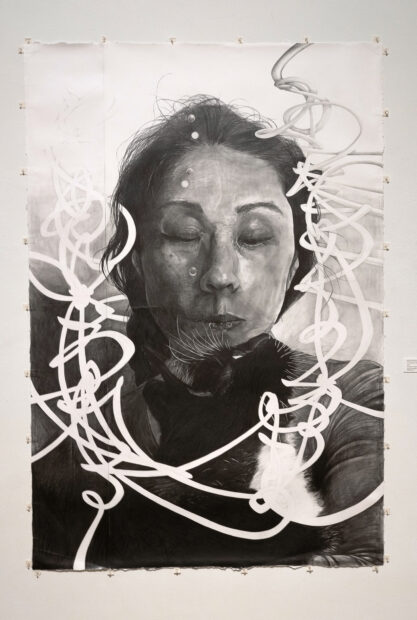

MOG: I don’t do any initial sketches. Instead, I take photographs around the house. Whenever I need a new work idea, I go through my images until I find something that’s interesting and work from there. When there is a photograph that I want to use for a large-scale piece, I put it in Photoshop and create an 8 by 8 grid. I can then print one section at a time in black and white, darken the backside of the copy with graphite, and just tape it up.

MG: We had the best bathtub ever where I do my reading, and it’s on the other side of this wall where Mayuko tapes up her work. So I’ll be drifting around in the bathtub in the morning, reading and drinking my coffee, and I’ll hear her on the other side of the wall drawing. She also has this new electric eraser, so I’ll also hear sounds as if I am in a dentist office.

Her process of is one of removal, and her work is fascinating because underneath the drawing she builds a trough out of paper. She buys erasers in bulk, so she’ll go through this process of turning all of these erasers into this powder, and the shavings fall into this trough as she starts working reductively.

SR: What about your process, Mark?

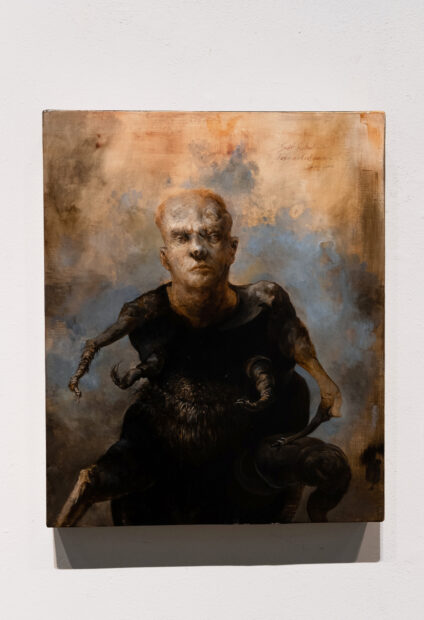

MG: I am interested in starting with a premise, and then watching the image grow and evolve as far away from that premise as possible. In a sense, I’m aging figurative imagery, so I have a lot of techniques for doing that. One technique is putting multiple images on top of one another through a gestural process. I might refer to Old Master drawings or photographs, or I might just develop figuration synthetically. The panels that I build are intended to maximize flexibility, and nothing in the technical process is ever going to stop me from making changes even to work that has been exhibited. I might come in and attack a piece that I’ve already shown, so my process basically is forming and reforming.

I’m also beginning to explore digital media.That’s a whole other life for a piece where the physical image can jump into a digital image and can evolve there. I think of my imagery like mothers and daughters — one image begets another image begets another image. What I’m doing is stacking imagery on top of itself.

SR: There is an organic focus to both of your work.

MG: My first love was biology, and I still would rather read about biology than read about art. The evolutionary theories of Stephen Jay Gould parallel my own process, in which the imagery evolves slowly. The changes in nature can be very incremental, but then you can slam an asteroid into the planet and create this drama. My technique for dramatic change is to take the surface of the image, spray water on it, take some sandpaper and just start sanding away on the surface. In the wet sanding, I’ll create this slurry on the surface. Then I take my rag, wipe away the slurry, and see what’s left. Sometimes I’ll reveal imagery that I’ve forgotten about because I’m constantly recycling this surface.

Another one of my interests is geology. My process is geological, too, because I’m going back in time with it. Everything on the surface is eroded like the Grand Canyon. I’m also looking for a way to surprise myself, like the surrealists did with automatic drawing and simultaneity.

MOG: I’m working on this series of pulsating still lives. The series is inspired by the way all matter that exists is composed of atoms that are constantly moving. I really love this idea. I am playing with the idea of bubbles inside matter. It is the actual energy that still lives and moves constantly as pulsating energy. But also the bubbles in my work are metaphors for how we start to break down, little by little. For example, in 42, I am looking at the cat, but the cat is looking at the bubbles. As I’m getting older, I’m losing my physical existence little by little.

Also, I write out Japanese proverbs in calligraphy — for example, the proverb “anything that will take form will break sooner or later.” Then, I start connecting the characters. Each word has one entrance in the top right, and one exit on the bottom left. These flowing characters are a metaphor for life. When you’re born, you have a physical body, but you begin losing your physical existence. These pictures depict energy fields where your body exists. My work is about life and death. We don’t know where we came from, what we’re supposed to do, and where we go when we die.

SR: What do you want viewers to experience in Cohabitation 2022?

MOG: I want my works to stop viewers. Viewers have their own right to interpret the meaning of the works, but I try to create work that is interesting enough to stop a viewer and allow them to have a little moment of detachment. That’s important to me. That’s why I like to refine details, so people who stop to look will have more to appreciate. In works like Mommy’s Baby, I use detail to honor the graphite and gray scale.

MG: I agree with that. I have the most respect for images that are arresting, that can stop people for a few minutes. I think artists have a tremendous amount of power through their ability to take raw materials and make something that is engaging. I also love the fact that I make artwork that is open to interpretation. My work is not just for art patrons: it is also for people who don’t know anything about art.

Mayuko Ono Gray and Mark Greenwalt’s Cohabitation 2022 is on view at the Dishman Art Museum through March 15, 2022.