The newly restored Leo Tanguma mural ‘The Rebirth of Our Nationality’ in Houston’s East End. Image via East End Houston.

The National Association of Latino Arts and Cultures (NALAC), a San Antonio-based non-profit organization that serves the needs of the U.S.’ Latinx arts community, has released a study that analyzes funding distributions to Houston arts organizations. Looking at the period from 2010 to 2015, the report examines grants and other monies given to the city’s arts and culture organizations by various funding mechanisms, including Houston’s Hotel Occupancy Tax (HOT tax); four private Houston foundations, including the Houston Endowment, the Cullen Foundation, the Powell Foundation, and the Albert and Margaret Alkek Foundation; and two governmental organizations, including the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the Texas Commission on the Arts (TCA).

This study was instigated due to ongoing conversation between Houston’s Latinx arts leaders and NALAC about the city’s funding inequities for artists and arts organizations of color. The conversation included the subject of the availability (or lack thereof) of data on the issue, so individuals from the community asked NALAC to look into arts funding in Houston. The idea was that with research and numbers to back up claims of inequitable funding, the city’s Latinx community could raise the issue publicly, and talk about possible solutions or first steps to remedy it.

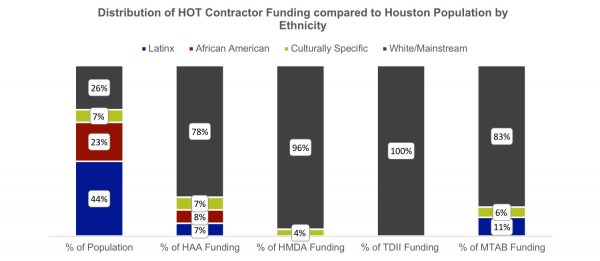

NALAC’s report found that funding to Houston’s Latinx arts organizations does not come close to reflecting the 44% of Houston’s population that is Latino, a statistic reported in Houston Arts and Cultural Plan (2015). For example, the NALAC study found that of the HOT funds distributed by the Houston Arts Alliance (HAA) (39.5% of total HOT tax funds for the arts), only about 7% went to Latinx arts organizations, while 78% of the funds went to “white/mainstream” organizations. The study concluded that additional HOT tax granting entities, which include the Theater District Improvement Inc., the Houston Museum District Association, and the Miller Theatre Advisory Board, didn’t do much better: since no Latinx organizations are geographically within the boundaries of the Museum and Theater Districts, the money earmarked for these areas (42% of total HOT tax money for the arts) is unavailable to them. As for the HOT funds distributed by the Miller Theatre Advisory Board, 83% were granted to “white/mainstream” organizations, while only 11% were given to Latinx organizations, and 6% were awarded to other culturally specific organizations.

A summary of the study’s other findings is below:

—Four Houston foundations (the Houston Endowment, the Cullen Foundation, the Powell Foundation and the Albert & Margaret Alkek Foundation) awarded over $110 million to the arts with less than 1% awarded to Latinx arts and culture organizations from 2010-2015.

—NEA grants to Houston organizations from 2010-2015 totaled $4,994,000, of which $55,000 was awarded to Houston Latinx organizations. That is 1.1%. (This percentage is expected to be updated soon, and slightly increased, as NALAC is looking into a small amount of funds that the study may not have considered.)

—TCA grants to Houston organizations from 2010-2015 totaled $5,624,866, of which $155,649 was awarded to Houston Latinx organizations. That is 2.7%.

It is important to note how the NALAC study defined Houston organizations in its report. When NALAC calls an organization Latinx, they mean that the organization’s mission “is explicitly focused on Latinx art and culture and has an Executive or Artistic director who is Latinx and/or a Board of Directors that is comprised of at least 51% Latinx.” Furthermore, the term “white/mainstream” refers “to U.S. Eurocentric culture and to identify people who are not ethnically or culturally marginalized.” The two other ways the report defined organizations were as African American or Culturally Specific. And while this NALAC study highlights Houston’s funding inequities for the Latinx community, it also found that these other categories of organizations didn’t fare much better, and in fact sometimes received less money than the city’s Latinx arts organizations, as can be seen in a graph from the report below.

This way of categorizing organizations means that an organization like the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), although it receives millions of dollars in funding for programs like the International Center for the Arts of the Americas, which focuses on researching Latin American and Latino art, is classified as a “white/mainstream” organization and therefore not included in the study. One of the reasons that this report paints organizations with such a wide brush is because breaking down programmatic funding within institutions is far more difficult than this initial study conducted by NALAC, both in terms of scope and cost.

Adán Medrano, who is a Houston-based author, NALAC board member, and HAA board of directors member, further contextualized this idea of an organization being “white/mainstream” from a cultural perspective: places like the MFAH present their programming from a Eurocentric point of view, and although they do present exhibitions and performances by and for non-white audiences, they organize them from a place within an organization whose mission can best be called, at least in terms of NALAC’s study, “white/mainstream.”

Mr. Medrano and NALAC are fully aware of the possible criticisms and discrepancies surrounding the uses of these terminologies, and NALAC says as much in a footnote of its study:

“What is considered mainstream depends on one’s point of view and cultural context. And every kind of cultural organization is culturally specific – ballet companies and symphony orchestras, for example, draw on and advance a specific culture. Our language evolves only in tandem with changing consciousness and demands for broader representation and inclusion. For this report, we choose to use the terms at hand.”

Maria López de León, the president and CEO of NALAC, along with every other proponent of this report I spoke to, emphasizes that the study presents an opportunity for Houston’s arts and culture community to collaborate, and that it is in no way designed to point fingers at any organization or institution, but instead is the first step in addressing Houston’s funding patterns. After all, a community can’t fix a problem it isn’t aware of.

One of the reasons Houston’s Latinx community leaders called for this study is because a full dataset of arts funding and demographics information doesn’t really exist. Granting organizations keep varying pieces of data and have different ways of classifying organizations based on the metrics they analyze. For example, Sunil Iyengar, the NEA’s director of research and analysis, says that it is important to understand that the NEA gives project-specific awards, and that the organization’s main focus is on the beneficiaries of the arts experiences that it funds. Therefore, because of the way it funds organizations across the U.S., the NEA doesn’t classify organizations the same way the NALAC study does. This is partially because there is no across-the-board standard of what information should be collected from granting organizations — the NEA instead relies on metrics that align with how it reports on its strategic plan, and how it looks at the arts around the country.

Mr. Iyengar points out that one of the NEA’s goals is to award funds to organizations and individuals within every congressional district in the U.S., meaning that the organization’s grants aren’t devoted entirely to urban areas. Also, an NEA online facts sheet shows that 36% of its grants go toward organizations that serve underserved populations, and that its funding distribution among small, medium, and large organizations is relatively balanced. Again, it is unclear how much these statistics overlap with the data found by the NALAC study, since there is no universal dataset that covers all breakdowns of these types of institutions.

Similarly, the TCA also classifies organizations differently than the NALAC study. Anina Moore, the TCA’s director of communications, mentions that some organizations defined by the NALAC report as “Latinx” may by be identified by the TCA as “multiracial.”

One metric that could be considered that the NALAC study did not track (and it admits as much within the report), is the number of organizations that apply to receive money from granting sources. The TCA’s Ms. Moore mentioned that in the timeframe of the NALAC’s study, no minority organizations were denied funding from the TCA, and that in fact about 98% of applications the institution receives in a given year are funded at some level. Additionally, the TCA meets a state-mandated guideline that 13% of its grant dollars every year go to organizations of color. (Of course, the TCA covers the arts across the entire state of Texas, so not all of this money was considered in the NALAC study, which looked only at funding for Houston organizations.)

When talking to some of Houston’s Latinx arts stakeholders, I was told that one ongoing issue around granting sources like the TCA and the NEA, however, appears to be the willingness and/or ability of smaller Houston Latinx organizations to apply for grants. Multiple sources who support the report claim that they know smaller Latinx organizations in Houston that have either had bad experiences applying for funding from places like the TCA and the NEA, or that these Latinx organizations feel that applying isn’t worth their time and energy. When asked about this, the TCA and NEA both pointed toward efforts they make to reach out to various communities.

In recent years, the TCA has held roundtable discussions with rural arts organizations, and representatives from the TCA regularly travel to various cities across Texas to raise awareness of its benefits. Mr. Iyengar at the NEA echoed these efforts, saying that senior leadership at the NEA has put an emphasis on traveling to places that the NEA hasn’t recently visited, in an effort to be present for all of its constituents. (For reference, NEA Chairman Jane Chu visited a Houston Art Alliance event and Project Row Houses in 2014.) The NEA also offers in-person grant workshops and online webinars for applying organizations.

Although these organizations continue to make efforts, many supporters of NALAC’s study think that there’s room for improvement. Mr. Medrano, who served from 1983‑89 as a commissioner on the Texas Commission on the Arts, likened the situation (and its possible solution) to a health crisis: when people are sick and not seeking treatment, and you want to stop an epidemic, you go to them, instead of waiting for them to come to you. In other words, the failure to receive applications from certain underserved communities is the failure of the granting institution, as it is the institution’s responsibility to reach out to communities and encourage them to apply for funding.

Ms. De León says that NALAC regularly encourages Latinx organizations to apply for NEA and TCA funding, and that in recent years, although there is still a big gap between potential and actual applicants, more organizations are actively applying. She also praises the TCA and NEA on the work they’ve done to diversify their panelists who select grantees, saying that nowadays there are both younger voices and more people of color represented on these selection panels. Still, granting inequities can be addressed as organizations continue to make a conscious effort to reach out to underrepresented communities.

The NALAC study offers some ideas for Houston going forward. The first step is that the greater Houston arts community recognize the problem, and address communication between marginalized organizations and the larger granting community. Second, the study states that Houston funders can face the problem of inequity by initiating more discussions with their underserved constituents. And finally, as mentioned above with the TCA and NEA, the study suggests making funding opportunities more accessible and equitable to underserved communities.

Another thing that the study’s supporters advocate is for more research on the issue. This NALAC report is a good first step, but there’s more information about funding in Houston that could be gathered and analyzed. For example, the NALAC study doesn’t look at individual giving, which, in a city with Houston’s wealth, makes up a significant portion of the funding received by organizations. A study expected to be released in November 2018, conducted by SMU DataArts, a program that researches arts and culture institutions, will touch on other missing data, as Zannie Giraud Voss, the program’s director, tells Glasstire:

“[The study] will provide an analysis of the demographic composition of both audiences and the workforce of arts and culture organizations in greater Houston, along with a comparison of how those characteristics mirror the population as a whole. It will report on demographic composition by a variety of factors such as role within the organization, employee age, and budget size.”

Some findings of the NALAC study are supported by the 2014 Arts and Cultural Heritage Community Indicator Report put out by the Center for Houston’s Future, a non-profit affiliate institution of the Greater Houston Partnership. In analyzing the greater Houston area (the nine counties that make up the Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown Metropolitan Statistical Area) during the period of 2000 to 2011, the report found that although the number of “ethnic and cultural awareness” non-profits substantially increased in the region, these entities received a smaller proportion of funding than other organizations. And although the Center for Houston’s Future’s report praises the rapid increase in Houston’s ethnic diversity in its organizations and its population, a bullet point in the report shows that there is still progress to be made:

“Though representing 13 percent of the region’s arts non-profits, cultural and ethnic awareness organizations account for less than 2 percent of the total revenue secured by the sector as a whole.”

Even before the NALAC report came out, Houston arts leaders took matters into their own hands and created the Houston Alliance of Latinx Arts (HALA). Founded to work on solutions to Houston’s funding inequity, the group focuses on four main goals: networking and professional development, artistic collaboration, political strategy, and funding advocacy. HALA consists of about 40 professionals, and hosts monthly self-directed meetings that allow members to discuss issues the Houston-area Latinx community is facing.

Post-NALAC report, the larger Houston arts community is still processing information, and there are differing ideas about how the city’s Latinx community should proceed. When talking to people invested in this story, I noticed (and some later pointed out), that Houston, unlike other cities in Texas, doesn’t have a civic Latinx organization dedicated to visual art. The city of Austin has the Mexic-Arte Museum, a space downtown that “is dedicated to cultural enrichment and education through the collection, preservation and presentation of traditional and contemporary Mexican, Latino, and Latin American art and culture”; Dallas has the Latino Cultural Center, which regularly hosts exhibitions of Latinx art and culture; and San Antonio has many entities dedicated to Latinx exhibitions and programs, including the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, and the Centro de Artes, among others.

This isn’t to say that Houston has no Latinx organizations that show art. Talento Bilingüe de Houston, and Multicultural Education and Counseling through the Arts (MECA), along with other organizations, do organize Latinx art exhibitions. These spaces, however, serve many other needs of the city’s Latinx community, and they aren’t dedicated art venues in the way that institutions in other cities are.

As for other available models, Ms. De León cites San Antonio’s Westside Arts Coalition, of which NALAC is a member, as a successful partnership that advocates for governmental funds for Latinx organizations in the city. She says that the coalition’s members, which include seven organizations besides NALAC (they are: American Indians in Texas, Centro Cultural Aztlan, Conjunto Heritage Taller, Esperanza Peace and Justice Center, Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, San Anto Cultural Arts, and URBAN-15 Group), recently received $200,000 in 2019 city funding that will help member organizations build visibility, membership, and programming.

Conversations will continue, thanks to HALA and other engaged community members. It is the hope of both NALAC and Houston’s Latinx art community that this NALAC study will be only the beginning of addressing the inconsistencies of funding in Houston, and that future studies, like SMU DataArts’ upcoming report, and others that will likely follow, will continue to examine the issue until it is properly addressed, and ultimately, righted by the the city and its funding entities.

In the meantime, Houstonians can look forward to the national Smithsonian Latino Art Now! 2019 conference, which will be held in Houston from April 4 – 6, 2019, in collaboration with the University of Houston. The event will be accompanied by the “Spring of Latino Art,” during which organizations and art spaces around Houston will host exhibitions and programs highlighting Latinx art and artists. Houston mayor Sylvester Turner recently announced that the program will receive a $25,000 grant from the city, with an additional $50,000 of in-kind support from Houston First. In a press release announcing the grant, Mayor Turner spoke about the hopeful future of Latinx art in the city, saying:

“This is just one of the strategies of the Mayor’s Office of Cultural Affairs to invest in Houston’s Latinx artists. From new grant programs for artists through Houston Arts Alliance to utilizing Latinx creative businesses, we have been expanding opportunities for artists and shining a light on our local talent.”

To read NALAC’s full report about arts funding in Houston, go here.