Jamal Cyrus and Jamire Williams’ exhibition, Boogaloo & The Midnite Hours, pivots on the tension between objects in the exhibition that suggest music and sound and the silence which pervades those artworks. As Charisse Pearlina Weston’s exhibition brochure essay makes clear, the show seeks to evoke the history and connections of music produced by African Americans from the period of slavery to more recent times.

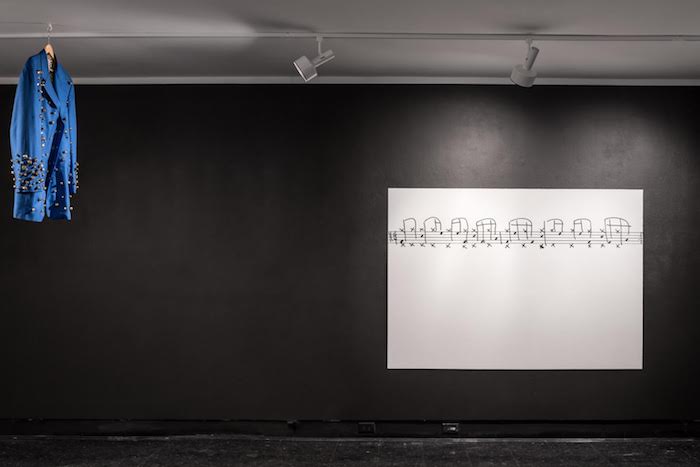

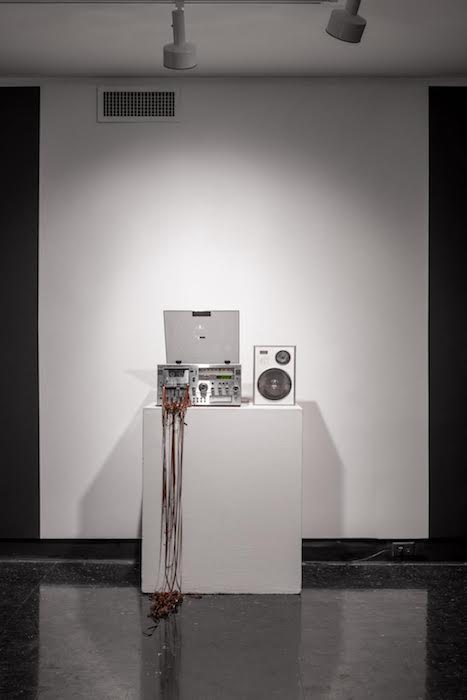

Throughout the exhibition, on the second floor of Lawndale Art Center in Houston, artworks that “should” make a sound do not. These include a stereo system, a blazer with bells attached, microphones, an Akai MPC 2000XL, and allusions to older musical instruments such as a root system and earthenware. In Til’ My Tape Pop (2018), the cassette tape’s ribbon is pulled out of the stereo system, no longer playable, and the record player is empty. Foundations 2 (2018), consisting of the Akai, cinder blocks, and cords, is also muted — and due to the cinderblocks, also out of reach. Bright Blue (2018), a blue blazer covered in bells, descends from the ceiling on a clothes hanger, not on a person — if worn, the work would be noisy. In the gallery it’s silent.

When you enter the installation, a work titled Foundations 1 (Stop All That Beating) (2018) commands your attention and sets the show’s theme. Six microphones and a cymbal surround a finely upholstered chair, set as if on a stage. This work, too, pertains to corporeal absence. The microphones and cymbal create anticipation for the absent occupant of the chair — absence and silence then repeat throughout the works in the show. Some of the microphones’ positions (one is behind the chair) suggest that even if someone occupied the chair, capturing the body’s sounds or words would be difficult. While the microphones wait to pick up on a sound, we await the person who sits in the chair.

Another work, Mighty Mighty Harmony (2018), resides in a different moment of music history. The album cover, enlarged so that no playable record could correspond to it, features an African-American musical group with group’s name missing from the cover. The songs listed suggest gospel music: None But The Righteous, Swing Low, and Glory Hallelujah’. These songs have a history in oral traditions of African American music. The identities of the musicians are in a state of erasure — their faces have been replaced by white paper with musical notations. Given the clothing of the group in the picture, the record is likely from the ’50s or early ’60s, which was a period in popular music in which record companies exploited (and stole) African Americans’ production of music through cover songs by white artists, and by paying African American songwriters and musicians significantly less than white performers.* Segregated musical charts and the practice of releasing music under such a category as “race records” persisted during this time. The white paper replacing the musician’s faces enacts this erasure and anonymity.

But the exhibition itself is not silent. There is music playing — yet mention of this is absent from the exhibition brochure and doesn’t come from any of the listed works. When I asked about the music, Lauren Lohman, at Lawndale, wrote to me that the music “was composed and performed by Jamire Williams and it begins with the boogaloo drum beat and the whole piece, about 7 minutes, acts as an evolution and celebration of drum beats. The artist declined to have it listed [as] a separate work in the show.” The music seems to be emanating near the objects least likely to make those sounds — Nok Mute (2017), made of earthenware, and Ritual Mute_1 (2018), made of a root system. Here’s a cognitive connection between the history of African-American music from its roots in Africa, to slavery, through contemporary music, made through aural and visual layering. Additionally, Weston in her essay cites James A. Snead’s essay Repetition as a Figure of Black Culture to support her points about historical sounds and music repeating and reappearing in “black performative acts” such as music and dance, which she also connects to visual and written culture.

Art historians Krista Thompson and Huey Copeland’s concept and term afrotropes is useful in elucidating how these artworks and sounds create these connections; the authors use the term to describe “recurrent visual forms that have emerged within and become central to the formation of African diasporic culture and identity,” using examples such as the slave ship icon created by British abolitionists in 1788 and the 1968 Memphis sanitation workers’ “I AM A MAN” signs, and how those images reappear under different conditions.** As Thompson and Copeland recently wrote, “..afrotropes are often translated across various cultural domains as well as transformed over time and space, accruing particular density at certain moments and seeming to volatilize out of sight at others. Their circulation thus illuminates both how black subjects have imagined themselves and reconfigured the visual technologies of modern cultural formation and image transmission more broadly.” The term itself is partly derived from Mikhail Bakhtin’s chronotrope, and this element of time — suspended, layered, both of the present and the past — is important. The past, history, has meaning in the present, and images from the past carry and modify within contemporary meaning. So, too, can sound. Music, in the case of this exhibition.

The relatively small gallery space evokes both a home-studio audio experience and an intimate performance space. The space, too, encourages these connections between earlier moments in music history and contemporary experiences of music. When you make your way up the stairs, you’re greeted by the exhibition title under blue light on the wall. The letters start to become indecipherable on the bottom row, layered to the point they are almost impossible to read. The meaning, the roots of the words — its letters — become too difficult to see. As Weston writes in the exhibition brochure about African American music: “A possibility made possible by the very fact of its intermingled, nameless beginnings and becomings.” Jamal Cyrus and Jamire Williams unpack the possibilities, meanings, and connections of music’s becoming and its contemporary presence.

At Lawndale Art Center, Houston, through March 25, 2018.

Images courtesy of Lawndale; photos by Peter Molick.

*See Brian Ward’s Just My Soul Responding: Rhythm and Blues, Black Consciousness, and Race Relations (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998) among many other examples of scholarship on the subject.

**Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson, Afrotropes: A User’s Guide, Art Journal, vol. 76 (Fall-Winter 2017): 7.