Nathaniel Donnett’s big, dimly lit black room is populated with objects heavy-laden with symbolism. Ominous and funerary. From either end of the oblong chapel-like space, two soundtracks toll different kinds of dirges: from the east end rolls a slow drumbeat; from the west, layered voices eulogizing dead African Americans.

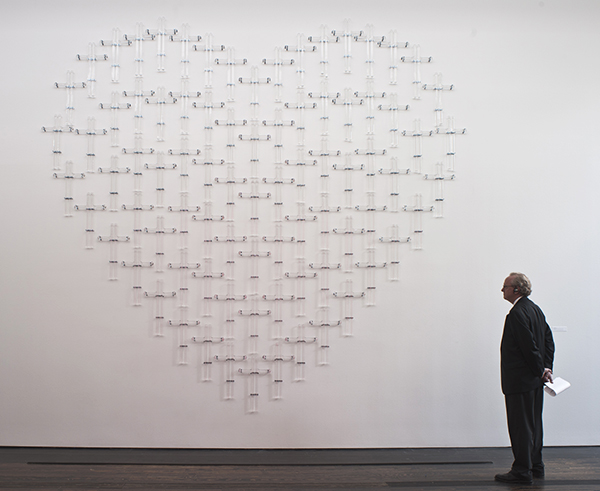

Heavy-handed? Yes. The most prominent feature of this dark cosmos is a wall-sized grid of black police batons crafted from wooden drumsticks, a dark mirror of Kendell Geers’ Cardiac Arrest, on view last year at the Menil Collection in the exhibition The Progress of Love. Geers’ piece, like Donnett’s, operates through surprising transformations: glass batons are paired to form crosses, which clustered to form a crystal heart.

Ritual 2014 (detail)

Kendell Geers, Cardiac Arrest, 2012

Donnett’s baton-transformation, titled Ritual, is comparatively rudimentary; it conflates traditions in Black music with traditions in White brutality with a single flip-flop. Two kinds of sticks, two kinds of hitting. Drumming as a weapon.

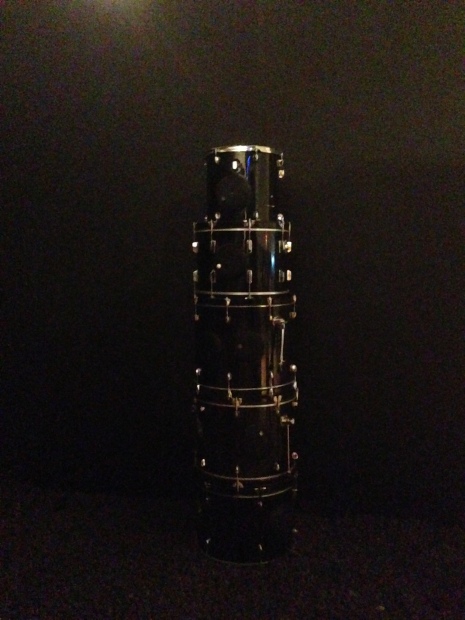

Continuing the theme, a stack of black drums forms a column or totem pole at the east end of the gallery. The drums have been mounted with inset speakers that fill the room with a low droning hum, punctuated at slow intervals by reverberating drumbeats. It’s as if a thunderstorm were approaching, or the ominous footfalls of an impossibly long-legged giant. Titled I Think I Saw It Move, it casts a day-of-reckoning foreboding over the whole exhibition.

Opposite the drum stack, at the far end of the long room, a wall of black-on-black hair and graphite collages and Disappear (eulogy), a sound piece collecting voices from old broadcast recordings, eulogize specific African Americans. A wall tag assigns the name of a martyr or an incident to each drawing like the inscription on a gravestone, prompting curiosity, but offering no further information.

Drawing wall

In other contexts where I’ve seen these drawings, which reiterate minimal modern-art compositions using areas of Black hair, they are pointed art-historical byplay, forcing a place for blackness in the all-white European modernist canon. Hung salon-style in Donnett’s sanctuary, their simple dark shapes still read more like Ellsworth Kelly or Richard Serra than funerary monuments.

Though the visual elements of Donnett’s installation are simple, schematic symbols, the sound is handled with uncommon finesse. It’s rare to hear sound integrated tightly into any visual art exhibit, and Donnett has balanced two tracks: a droning textural background (a sound piece designed with Markus Cone of Chin Xaou Ti Won specially for Donnett’s installation) overlaid with tinny, dated media interviews. Listeners moving from one end of the long gallery to the other are always aware of both, even as they focus attention primarily on one or the other. Differences in timbre, speed and style between the two soundtracks reiterate the mingling of two poles of feeling about the dead referred to on the piece’s west wall: mournful commemoration on one end, vengeful anger on the other.

Right Here, Right Now: Houston will be on view in the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston through November 30, 2014.

2 comments

3… 2… 1…

* 4 * But nah Robert not really. The review is, what it is. lol -but on another note- the sound piece was a COLLABORATION designed by Markus and I. We were both in the studio. I play a little music too. It’s on the didactic. I know it’s pretty black in there and you could’ve missed it. Historically, some folk think if there’s no white savior with an S on the chest to save the day for black artists, then the work isn’t worthy or gets dismissed. I call it the Benny Goodman, Elvis, Eminem, Vanilla Ice syndrome. But no one from Houston, Texas suffers from that. ; ) but for those who do, I wanted to clarify. Carry on.