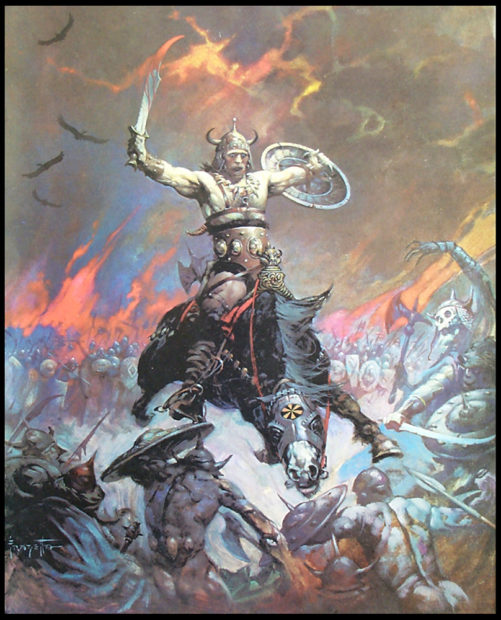

The Death Dealer (1973)

Time is a great equalizer, I know. Last night on Facebook I posted a picture of Frank Frazetta’s The Death Dealer (1973) with a caption that he should be my avatar for Glasstire. The enthusiasm for seeing such a beloved old Frazetta image was immediate, and the likes poured in from artists (some of the best I’ve personally known), art dealers, art writers, curators, architects, lawyers, musicians, and graphic designers. Mostly artists. Our Death Dealer lives large in the hearts of many, it seems, and we’ve certainly reached a point in time when we just embrace him without question. He is family.

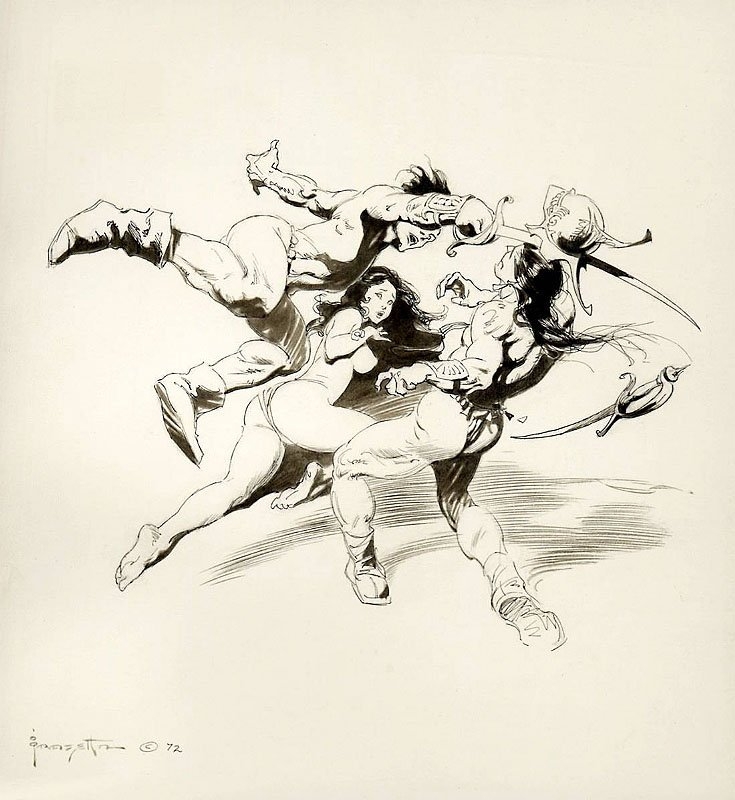

Nostalgia has ruled pop culture for 20 years now, but Frazetta is extra special. When I told Michael Bise I felt like writing about Frazetta (I get nostalgic at the end of every summer) and asked him what he thought of him, he shot back immediately: What’s not to like? Come to think of it, Bise’s avatar for Glasstire could be the The Death Dealer. But more likely Berserker.

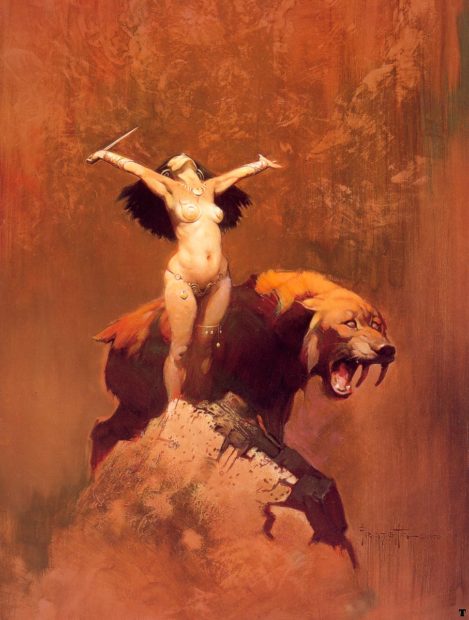

Berserker (1975)

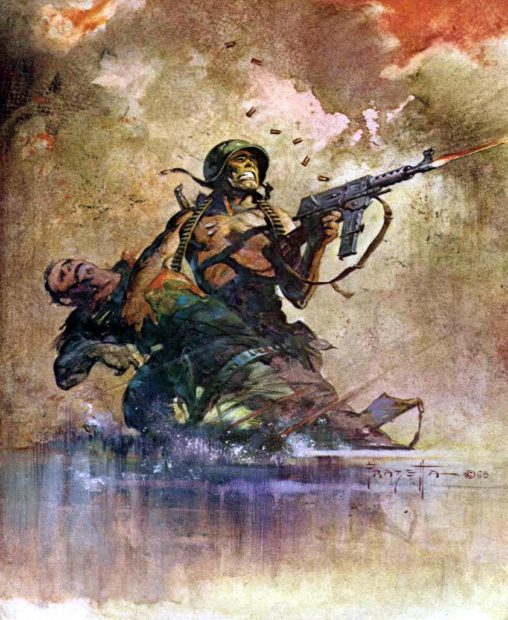

I would guess that, spanning at least three generations, Frazetta’s work hit a certain kind of adolescent mind like a ton of bricks and that was that. We were imprinted. The drama! The urgency! The sex! The fantasy! Given that Frazetta’s heyday and highest point of commercial exposure was in the mid ‘60s through the early ‘80s, when the world was still analog and people were still going to bookstores all the time, anyone born from about 1945 to 1980 must have first encountered his book cover illustrations (though the comics readers would have seen his work far earlier) and gravitated to them whether one was into pulpy sci-fi/fantasy or not. That’s how much his work stood out. His compositions are amazing; there’s plenty of studied Rubens in there. Frazetta’s Conan and Tarzan and John Carter pictures were his most famous, and then the ubiquitous Ballantine books of his plates started rolling out in 1975. He’s influenced so many artists and illustrators and comic book creators and filmmakers that if he were to be re-animated now (because that’s how it would have to be; he died in 2010) and taken to Comic-Con, the Rapture itself would break out.

Conan the Destroyer (1971)

Duel (1972)

Moon Maid (1973)

I was about seven when I guilted my dad (getting a divorce from mom) into buying me the first Ballantine book of Frazatta’s illustrations. This was R-rated stuff for a little kid, and I certainly didn’t understand the concept of taste, or that at that time conceptual art and the post-abstract and pop-art pedigree made Frazetta’s images seem decidedly low and kitsch in the eyes of the art world. His work is low and kitsch. It’s like Charles M. Russell and Tom of Finland flew to Mars, hooked up with a young Bo Derek there, and had a kid. (What’s not to like?) Though most of the originals are oil paintings, the images are designed for mass reproduction. And one of the reasons fine artists can love Frazetta unconditionally at this point is because Frazetta never attempted to cross over; he was always a commercial illustrator and never claimed to be otherwise. He understood his calling. When I was in my 20s and starting to write art criticism, I don’t know what my admitted relationship to Frazetta’s work was. I had his books and knew every line and shadow of countless of his illustrations. And I assume I never talked about it.

Madame Derringer (1976)

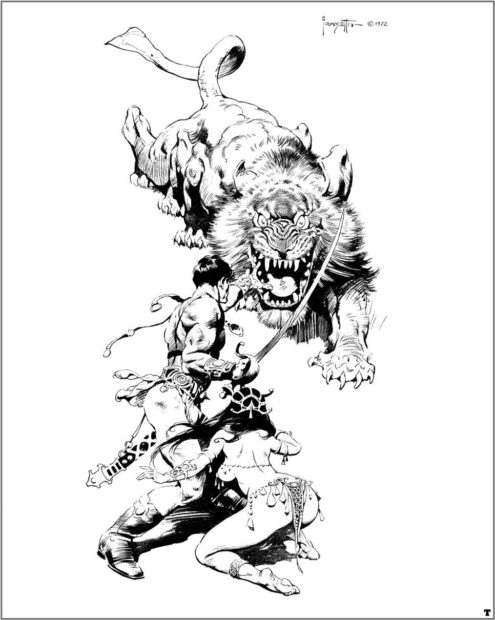

Banth (1972)

My thesis here is that Frazetta has been a generous and lively ongoing foundation for artists all these years, whether an artist’s work is in the least bit narrative or not. Because something has to happen to a young mind to convince it that a static image can be a massively powerful and inspiring thing, and worth trying to make. And there has to be a personal reference to this first major encounter. The great album covers of the ’60 and ‘70s were probably plenty of inspiration for the future artists who missed Frazetta (though his work graced a few album covers; a lot of great illustrators’ did). It’s no wonder that art critics and curators and dealers love Frazetta as well, because at least a part of art appreciation springs from the idea that a creative mind can, totally from thin air, make a picture that freaks you the fuck out. You see it and your world has changed; your imagination has been expanded.

Combat (1965)

Sun Goddess (1970)

Middle-Earth (1975)

We grow up looking at art, and at some point we realize it doesn’t always take a ton of bricks (i.e. roiling Viking muscle, spurting blood, perfect teardrop tits, and extended banth claws) to have this effect. We move, in our education, from broad to finer to fine. We grow up, and are impacted by a painting, a photograph, a drawing, a digital image whose subtlety certainly escapes the appreciation of a seven year old. And I’m not implying that Frazetta functions only as a set-up for high art appreciation. His work still has the power to make one feel (immediately, without reflection) tense, aroused, dazed, amused, grief-stricken. I don’t know a single person with feelings who wouldn’t respond to the emotional content of many of his images, whether they’re bewildered afterward or not. I will admit that most artists, even if they love Frazetta, have shed any direct evidence of his influence by the time they get to art school. Maybe not Lisa Yuskavage, but anything that looks too much like something that might show up on DeviantArt is to be overlooked, of course. And I wonder if this is a little bit of a shame.

The likes on that Facebook post continue to roll in.

8 comments

Great article. I didn’t start reading until fairly late as a kid, but my older sister read a lot. I would spend hours staring at the covers, and clearly my two favorites were Frazetta and Chris Foss’ sci-fi images. I’ve come to embrace the influences these image makers had and continue to have on me.

That shit looks boss painted on a van!

I doubt that it shows, but Frazetta’s covers for Creepy and Eerie Magazines and his paperback covers are what made me take up painting instead of restricting myself to pen and ink like the comic book artists I emulated as a kid. What a great essay to read. Thank you, Christina.

Probably my first awareness of Frank Frazetta beyond comic books and magazines was that other mass medium idiom, the album cover, which in those days, whippersnappers, was a large 12″ X 12″ square. Georgia southern rockers Molly Hatchet’s first three LPs covers bore Frank’s iconic imagery of either Teutonic warlords in battle or a vague Middle Earth figure of doom (1973’s “The Death Dealer”, 1976’s “Dark Kingdom” and 1975’s “Beserker”); if you were a young male of a certain age, you sought this stuff out, shared it with your friends, exasperated your concerned parents and probably bored the pants off a few other enthusiasts of Conan-like imagery who read Heavy Metal but had their own similar artists like Boris Vallejo and Paul Gregory. For me it was part of the journey and opened up newer and different worlds to visit. Thanks, Christina!

Christina, thank you for writing and posting this. I grew up reading Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert E. Howard, and the cover art on those books was always awe inspiring. In fact, I daresay that work inspired me to start modeling for art classes in 1984, and I wondered early on if any of the students drawing me would one day do book cover art like that. I still model as often as I can, even though I turned 50 this past weekend, and now I just appreciate any artistic representation of my body. How many careers have launched because of adolescent fandom?

I was a senior in high school in 1979. I owned the paperback book with all of these Frazzeta images. I liked rock n’ roll, drawing and I was an athlete. I would listen to Thin Lizzy’s “Warrior” Or “Cowboy Song”, look at the images, redraw them, put on the headphones and then become the person on the page. I was a State Champion Wrestler. The image of men like Conan and the Goddess girls was the stereotype (but never gets old) of Beauty and Beast. Those images were the perfect combo to the sex appeal and the drive of hard core music and this drove my motivation to win. A great example of how art and music intertwine and how all of the above affect a boy with raging teen spirit.

I became a voracious science fiction fantasy reader in the ’80s and happened upon the death dealer on the cover of James silkies books and gath of ball seemed like words from frazetta’s paintings the words in the image are so intertwined that to open one of those books I need to rest up because it is an exercise thank you Frank thank you Christina

Frazetta has been my inspiration since I first saw his Conan berserker cover when I was a teenager. It was displayed in a book shop window as I was passing in a bus. It knocked me for six and caused me to jump from my bus to get a closer look so I had to walk the rest of my journey home. I now work as a fantasy illustrator.