The LA-based assemblage artist Ed Kienholz had already perpetrated several of the most powerful pieces decrying the ongoing carnage then transpiring in Vietnam when, in 1970, he came up with an idea for what could well have proved his best one yet.

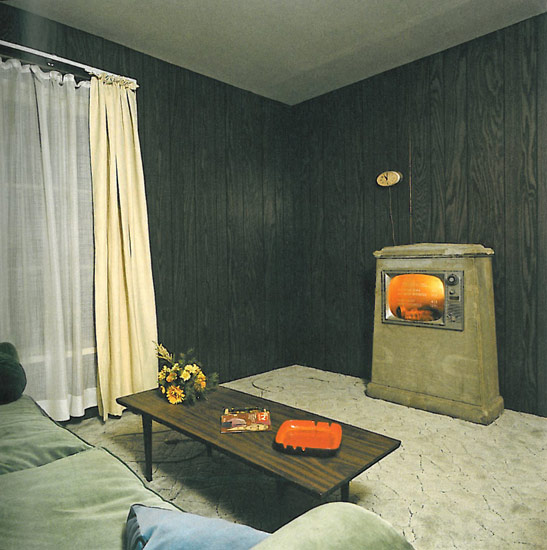

A couple of years earlier, in 1968, he’d realized his Eleventh Hour Final tableau, a room-size contemporarily furnished nondescript living room—wood paneled walls, a kitsch painting of an urban skyscape hanging over the well worn sofa, a low table with a big empty ashtray, a vase full of plastic flowers, and a TV remote control unit from out of which wended a long electric cord (as they did in those days) connecting to the TV set on the far side of the room, which (now that one looked more closely) was embedded in a big cement tombstone. The illumined TV screen broadcast:

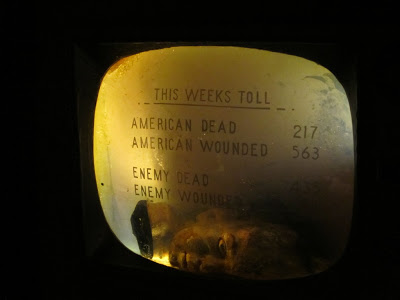

This Week’s Toll

American Dead 217

American Wounded 563

Enemy Dead 435

Enemy Wounded 1291

And now that one gazed in a little closer, one could see, settled at the bottom of aquariumlike TV tube: a severed 3D mannequin head, its nose smudged against the glass, its vaguely Oriental eyes, open.

That same year, 1968, had likewise seen the completion of Kienholz’s even more ambitious and more blatantly sardonic Portable War Memorial, a mash- and send-up of American consumerism-cum-imperialism, with the ghosts of the iconic Iwo Jima crew planting their standard into the aluminum tables outside a conventional diner as Kate Smith, embedded in an upturned garbage can over to the side, belted out “God Bless America.”

People sometimes forget how three years before that, in one of his most famous pieces, his two-thirds-size reincarnation of Barney’s, the sleazy down-and-out neighborhood Beanery (with its uncannily realized clock-faced denizens crammed together inside, slouching and loitering, oblivious, killing time), the headline on the newspaper in the weathered stand just outside had read: CHILDREN KILL CHILDREN IN VIETNAM RIOTS.

Anyway, during the two years immediately following 1968, Kienholz focused most of his energies on arguably his greatest and most harrowing piece to date, his evocation of the fraught crossroads where race and class and sex and violence keep intersecting across American history, the castration/lynching tableau Five Car Stud.

But in the midst of completing that piece, he returned to the gnawing, gaping open wound that was the country’s still continuing involvement in Vietnam, with the proposal for a piece that, had it ever been realized, could have been every bit as wrenching: The Non War Memorial.

“America has long been engaged in a great civil war (theirs),” he launched out on his page-long prospectus for the project,

testing whether our nation or any nation, so deceived and so divided, can long endure. The end at long last seems possible, and as the killing slows, I would like to make a war memorial from approximately fifty-thousand (50,000) pairs of surplus army uniforms tied at the wrists and ankles and pumped full of slurried clay. These corpse-bodies would be left to lie at random on a 75-acre meadow close to Clark’s Fork, Idaho. This land is now a beautiful field of alfalfa and wild flowers that gently slopes down to the river. All vegetation will be plowed under and perhaps the soil killed chemically. A temporary camp for living would be established on the river and heavy equipment leased for the actual construction.

He subsequently told me he’d just wanted to see how much time and effort it would take to create all that death (by the time we were talking, a few years later, the number of US military deaths had risen past 58,000). In his original proposal, he’d gone on to surmise that

Workers will be a mix of artists, students, activists, etc. willing to spend a summer making visual an non-war memorial and local residents interested or curious enough to help. All will be paid, and the production schedule will be a mandatory five hundred (500) bodies a day, seven days a week, for over three months.

He also told me he’d intended to invite the relatives of the various dead soldiers to come and “identify” their boys, maybe to leave individual keepsakes (dog tags, medals, ribbons, notes). A non-war memorial, he told me, because, after all, what had been the point? What on earth was there to celebrate?

When completed [he concluded], the Non-War Memorial will be entrusted to a museum for a five-year period, during which time the uniforms will rot, the clay dissolve, and finally the land will again be plowed and planted back to alfalfa.

In the event, Kienholz was never able to realize the project, settling instead for a gallery version, for which he produced a telephone book-sized volume consisting of page after page of photographs of 50,000 such slurried clay corpses (though in fact he’d just photographed a half dozen or so such mock-ups, reproducing the results rightside up and upside down and sideways and backwards and so forth, till they initially read as 50,000 separate corpses), and displaying the book in a vitrine buttressed by five or six actual mud-bloated army surplus cadavers. Powerful: but not nearly as gripping.

This was all, however, a good decade before the country as a whole finally got around to honoring its Vietnam dead with Maya Lin’s brilliant, minimalist, pitch-perfect black granite gash off the side of the Mall in Washington DC (1982): with the two wings of the spread-eagled monument starting at ground level and then ever so slowly sloping down toward the ten-foot deep apex, offering visitors a sense of the gradually engulfing quagmire as they slowly filed down the facing path, every single name accounted for, incised into the successive stone plinths in the chronological order of their dying, the whole thing presently swallowing up the hordes who came to visit, to “pay their respects,” to “come to terms,” to “bear witness,” who in turn presently came to see themselves mirrored, ghostlike, in the black polished granite, or was that even them, was that not perhaps rather their lone-gone loved ones in their own milling hordes, staring back, mute , all of us, all of us, tongue tied, heartbroken?

This was all, however, a good decade before the country as a whole finally got around to honoring its Vietnam dead with Maya Lin’s brilliant, minimalist, pitch-perfect black granite gash off the side of the Mall in Washington DC (1982): with the two wings of the spread-eagled monument starting at ground level and then ever so slowly sloping down toward the ten-foot deep apex, offering visitors a sense of the gradually engulfing quagmire as they slowly filed down the facing path, every single name accounted for, incised into the successive stone plinths in the chronological order of their dying, the whole thing presently swallowing up the hordes who came to visit, to “pay their respects,” to “come to terms,” to “bear witness,” who in turn presently came to see themselves mirrored, ghostlike, in the black polished granite, or was that even them, was that not perhaps rather their lone-gone loved ones in their own milling hordes, staring back, mute , all of us, all of us, tongue tied, heartbroken?

Strange, though, how similar was the impulse behind the two memorials—Kienholz’s and then Maya Lin’s—the insistence on the way that attention must be paid first to this one, and then this next one, and then that other specific mother’s son, and then the one after, each and every single one given its rightful name (or at least the possibility of such a naming, and such an in-gathering).

And strange, too, alas, how both Kienholz and Maya Lin of course got it all wrong. (Perhaps it couldn’t yet have been helped, not at the time, but still….) For the Vietnam War of course didn’t just cost 58,000-some-odd lives: it consumed the lives (and for what?) of more on the order of something like two or three million individuals. “About such things,” the Polish master Zbigniew Herbert had warned his own fellow countrymen in the wake of the Second World War in a celebrated poem highlighting the need for precision, “we must not be wrong / even by a single one. // We are, after all / the guardians of our brothers. // Ignorance about those who have disappeared / undermines the reality of the world.” And it is America’s persistent obliviousness to that fact—the way that time and again we only seem to register (if and when we register anything at all) our own casualties, discounting to virtual nonexistence the lives of all those others we grind and gnash into our collective fever dreams—that may be the thing that makes it so easy for us to keep repeating the nightmare, as we so constantly and ever-so-heedlessly seem to do.

Chris Burden, The Other Vietnam Memorial, 1991. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

The artist Chris Burden seemed to have registered this problem, for ten years after the dedication of Maya Lin’s monument, in 1991, he produced his own, slyly dubbing it The Other Vietnam Memorial: a thirteen foot tall cylindrical column, a towering Rolodex on its side, splaying out dozens upon dozens of revolving copper plates, each containing thousands of inscribed Vietnamese names, something like three million in all. And you could go up and leaf through them all, one panel and then the next, till it got to be too much.

The trouble with Burden’s gesture, though, is that no such actual list of Vietnamese names was ever compiled—the slaughter was just too pell-mell and wholesale industrial—so he had to have recourse to a problematic expedient, combing Vietnamese phone books for 4000 representative names and then mixing and matching those into random three-names combines: a process almost as pell-mell and wholesale industrial as the slaughter it was aiming to condemn and consecrate.

But what if now, over twenty years after that, we were to return to the challenge once again? What if we went back to Maya Lin’s monument and looked at it afresh, understanding that a true Vietnam monument memorializing all the dead of that terrible war, would, were it to express the same proportions, have to be over forty (rather than ten) feet deep (four stories!), with wings stretching over a thousand (rather than the current 250) feet long (over three football fields!) in both directions. Or, if we kept the current ten foot depth at the apex, the wings to either side would have to go on for close to two miles, past the Lincoln Memorial across the Potomac and on past the far side of Arlington Cemetery, to one side, and to the other, past the Washington Monument and on into the rotunda of the Capitol Building (where it might rightly belong!)

I realize, of course, this is never going to happen: and there’s still the problem of the names, we don’t have the two million and never will.

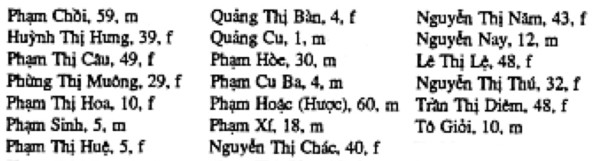

But here are the actual names (and ages and genders) of a mere twenty of the Vietnamese dead (taken as it happens, from a list of the 504 civilians who died on a single day, March 16, 1968, at My Lai):

(List provided, many years later, by the Embassy of Vietnam in Washington DC in response to a request by Trent Angers, author of The Forgotten Hero of My Lai: The Hugh Thompson Story.)

What if we inscribed just those names onto a slab of polished black granite and then one night found (or quickly excavated) ourselves a little hollow somewhere on the Mall in the line between the current Vietnam Memorial and the Capitol rotunda and then wedged the slab in there perpendicularly vertical, straight and true. And just left it there to be happened upon by passers by. Just to give people some little sense of the kind of acreage a real monument would need to encompass.

After which, perhaps, we could set to thinking about how we are ever going to memorialize our Iraqi and Afghani war dead, for they are all of them all of ours.

In fond and abiding memory of my own master, Jonathan Schell (1943-2014).

3 comments

Most poignant, thanks.

More of Weschler’s substantive writing, please.

Maya Lin’s black wall memorial was the best and the only one needed for that damned Viet Nam War.

Peace, Terry J. DuBose

Viet Nam, 1967-1968

Shameless I know but related to this article is a piece called Body Count that I showed at the Station Museum of Contemporary Art…

http://www.stationmuseum.com/index.php/exhibitions/19-exhibitions/132-hx8-prince-varughese-thomas