Angel Oloshove is relatively new to Houston but has already garnered attention for her unique whimsical ceramics. In 2012, Oloshove was Lawndale Art Center’s Big Show winner and soon after, some of her pieces were up for grabs at Myth + Symbol, one of Houston’s premier boutiques in Rice Village.

Working out of the Museum of Fine Arts Glassell School‘s ceramics studio, her conceptual process is what makes Oloshove’s work so intriguing. Her craft skills come from years of working on her technique and her influences stem from an array of pop culture references. “I think a lot about movie props like Freddy’s hat in the dreamscape in Friday the 13th or the dishes the Flintstones would use,” Oloshove says.

In contrast to Freddy and Fred Flintstone, she also strives for divinity in her work—a sense of transcendence. With ceramics that are utilitarian in nature, Oloshove hopes her pieces can permeate the sanctity of someone’s daily ritual. In this way, the artworks become a part of someone’s life, reminding them of forgotten acts like drinking the morning coffee. According to Kant, transcendent refers to a knowledge that lies beyond experiencing objects and elucidates the way the mind forms knowledge of objects. Similarly, Oloshove hopes to interject a reminder of that elusive consciousness by creating utilitarian objects that playfully interfere with the status quo of daily activity.

Originally from Michigan, Oloshove’s father worked at the Jeep plant during a time when job security was at an all time low. “My family would protest during that time. I didn’t know if my dad’s factory would close and I wondered why were they taking jobs away from actual people so machines can do the job instead,” Oloshove recalls. This experience sparked a DIY spirit which led to her working with her hands and enrolling in ceramics classes in high school. “I was sixteen and it was me and a bunch of goth girls. I remember thinking that was really cool.”

Oloshove considers herself a “maker,” a term that defines not only her level of craft but the sense of her hand in her work. Every piece in the studio and at her Houston home reflects a personal involvement that is not only handmade but also imbued with her personality. The works are a bit quirky, clumsy even, but they are also tremendously thoughtful. These pieces simultaneously feel forgotten and treasured, like toys that once accompanied you everywhere your parents forced you to go.

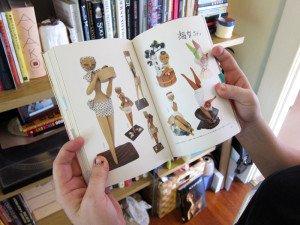

After high school, Oloshove studied at California College for Contemporary Arts and Crafts (now CCA instead of CCAC) during a resurgence of the sixties craft DIY movement. “Everyone was wearing scarves and being romantic,” Oloshove reflects. Soon after graduating she moved to Japan and took on a much more involved craft practice. Working in toy and doll production for a Japanese-based company, Oloshove met toy fabricators who were supremely talented and had honed their techniques for many years.

After high school, Oloshove studied at California College for Contemporary Arts and Crafts (now CCA instead of CCAC) during a resurgence of the sixties craft DIY movement. “Everyone was wearing scarves and being romantic,” Oloshove reflects. Soon after graduating she moved to Japan and took on a much more involved craft practice. Working in toy and doll production for a Japanese-based company, Oloshove met toy fabricators who were supremely talented and had honed their techniques for many years.

After six years in Japan, Oloshove returned to the U.S. not only with a much greater knowledge of Japanese ceramic techniques, but also with an understanding of toy culture that influences her work to this day. In Japan, as in most countries, handmade dolls are psychologically some of the most interesting pieces of sociological history. Not only can dolls denote a specific time in a culture, they are small, malleable representations of larger beings made accessible. Whether a traditional Kokeshi from northern Japan or a Hello Kitty plush from Tokyo, the owner of a doll can project any semblance of his or her emotions and ideas upon it.

After six years in Japan, Oloshove returned to the U.S. not only with a much greater knowledge of Japanese ceramic techniques, but also with an understanding of toy culture that influences her work to this day. In Japan, as in most countries, handmade dolls are psychologically some of the most interesting pieces of sociological history. Not only can dolls denote a specific time in a culture, they are small, malleable representations of larger beings made accessible. Whether a traditional Kokeshi from northern Japan or a Hello Kitty plush from Tokyo, the owner of a doll can project any semblance of his or her emotions and ideas upon it.

Like her ceramics, Oloshove’s Houston home is filled with thoughtful gestures and handmade art works. One of her favorite keepsakes is a wind-up cat from about 1910 that we couldn’t stop laughing about:

In front of the bed is a Ken Price poster for inspiration, a sun hat, and a collage by local artist Steven Hook.

Special thanks to Angel Oloshove for sharing her studio, home, and amazing collection of cool stuff with me.