Like a good dose of The Twilight Zone, Celia Eberle’s latest show, Sweat, shakes up prescribed notions of happily ever after.

Fairy tales, grandma’s patchwork quilt, and plush cushions—all of these seemingly innocuous bedtime comforts turn nightmarish in Eberle’s latest artistic venture, on view at Dallas’ Mulcahy Modern Gallery.

Eberle’s two previous exhibitions at the Mulcahy Modern showcased her forays into faux porcelain and manipulated stuffed animals. Each of these bodies of work was acclaimed for its perverse ability to play on ingrained fears and desires. Her most current work, however, trumps all. Sweat morphs the gallery space into a personalized bedroom environment, luring the visitor into what seems, superficially, like a familiar setting.

The absence of distracting wall text, as well as the unconventional arrangement of works at various heights and distances, engenders an unusual gallery experience. Shadow, an enlarged black butterfly appliquéd on white, delicate fabric, hangs like a banner in the gallery front’s window, beckoning visitors. With suspiciously welcoming bright pinks and oranges, two oversized pillows lay on the floor. These gigantic cushions (72 x 12 x 12 inches and 58 x 58 x 16 inches) disrupt our sense of scale. Are the pillows several times larger than normal, or have we, like Alice in Wonderland, shrunk into a fantasy world? Throughout the exhibition, Eberle questions our perception of reality, tweaking here, adjusting there. She skews our awareness of the space just enough, but not too much, so as to retain the initial charm of her objects.

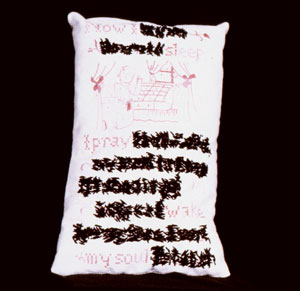

At the far end of the gallery, Eberle cloaks a bed with a patchwork quilt and caps it with an array of small pillows. A restful haven? Not a chance. Stitched into these domestic dressings are disturbing details — fox paws, doll wigs, dismembered action figures. Toy figurines are captured in gauze like spider’s prey, pinned into the bedspread’s web of fabric scraps. On one pillow, black crosshatches obliterate key phrases of an otherwise tranquil “Now I lay me down to sleep.” This, truly, is like no other recital of a nighttime prayer. Above the bed dangles a heart-shaped pillow, stabbed through with a miniature rapier.

Eberle’s world is fraught with suspended narratives. Falling, a hanging quilt, displays a fairy tale gone awry as a female figure, outlined in red thread, plummets from a turret. Below, staged behind two bush-like shapes, are two comically mean little monsters with pointy ears and jagged teeth. Are they waiting to devour the hapless woman? Will she survive this chapter of her life? The fate of the figure remains untold. Our apprehension of impending doom is blanketed by the floral motifs, polka dots, and stripes of the background. Eberle juxtaposes the pattern of the cloth—predictable, ubiquitous—with the assumed pattern of fables, also predictable. The stories she weaves, though, do not have conventional, hardened distinctions between fact and fiction. They creep into found objects, specimens of domestic life. Eberle baits us with these household items, which engage us in an alternate reality. Leaving the finale up to our imagination, she implies an open-ended narrative. This provocative ambiguity is much like that found in contemporary painter Amy Cutler’s bizarre, allegorical pictures. Instead of Cutler’s fanciful whimsy, though, Eberle’s compositions compel the viewer with edgy anticipation.

In the embroidered The Butterfly Costume, Eberle produces an inventive, Eden-like scene akin to Hieronymus Bosch’s early sixteenth-century painting Garden of Earthly Delights, but without the moralizing overtones. Like Bosch, Eberle cross-fertilizes creatures and reverses natural proportions, so that humans, birds, and flowers engage with each other in unexpected ways. Unlike Bosch’s depictions of the crowded, infernal afterlife, Eberle’s scenes explore the more individualized mysteries of the subconscious.

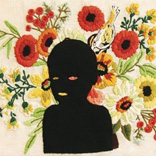

Subtle threats, like menacing whispers, pervade the gallery installation. Eberle subverts the traditionally feminine and docile craft of sewing in her series of appliqué on found crewels. In these works, she imposes silhouetted figures on colorfully embroidered floral arrangements. In contrast to the lively hues of the background, the foreground figures are starkly inert. As memento mori, their dark presence is a reminder of the death that inevitably follows fecundity. The most jarring of the altered crewels is Secret Garden, which features a young child’s bust surrounded by yellow, orange, and red flowers, as well as a bird with its beak disappearing behind (into, perhaps?) the child’s skull. Where the youth’s eyes and mouth should be are, instead, vacant orifices. The silhouetted figure is an eerily empty mask through which we view the scene behind. Has the bird, like some awful parasite, sucked out the child’s insides, his humanity?

Celia Eberle(on left) Big PillowFound fabric, foam; 58 x 58 x 16 inches

...Neck Roll; 2004;Found crochet, fabric, foam; 72 x 12 x 12 inches

There’s no letting up of emotional tension in this show, not even in the back gallery room, beyond the bounds of the main exhibition. From a narrow, high-up window, the same face from Secret Garden glowers down, omnipresent. The eyeholes, accentuated with red light, gradually intensify and then wane. This work, which shares the name of the exhibition, literally makes us sweat. With Eberle’s fabrication, unsuspected crevices—of the room, our conscious, and our subconscious—become hauntingly charged.

In the peculiar twilight of Eberle’s installation, we are left to wonder, will everything simply end happily ever after? Don’t count on it.

Images courtesy the artist and Mulcahy Modern Gallery

Catherine Deitchman is a writer living in Dalllas