The Museum of Modern Art is a one-of-a kind institution, but it has always had two faces.

There was a time, long before Vietnam and postmodernism, when modern meant progress. MoMA was conceived in part to embody this idealistic, “better living through aesthetics” notion. There was also a time — the same time — when modern art was viewed as heresy or worse (this violent contrast embodied by MoMA co-founder Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and her thoroughly nineteenth-century husband, John D. Rockefeller, Jr.). Such polarities seem particularly timely (another spoonful of 50-50 government, anyone?). The two MoMA’s — one dedicated to encouraging living artists, the other determined to preserve a modern legacy — create a dynamic tension that make the Museum of Fine Art, Houston’s presentation of The Heroic Century much more than just another comfortable procession of collection highlights.

Alfred Barr and his trustees initially imagined their institution as a frisky hybrid dedicated to the modern aesthetic as an exemplar of progress. This side (the left brain, if you will) encouraged contextualizing painting and sculpture with architecture, design, graphic arts, photography, and film. This side of the museum “brain” enunciated the institution’s first collecting policy, envisioning that no artwork would remain in MoMA’s collection for more than 50 years. But the Museum’s right brain quickly kicked in after early purchases (augmented by key bequests from founding trustees) began to accrue significant market value. Needless to say, the right brain won the battle, but the left has kept its oar in.

The assembled artworks are icons that show, in the words of MFAH director Peter Marzio, “the anatomy of 20th century and contemporary art.” Taken as a whole, they reveal MoMA’s greatest achievement to be the construction of the modernist template adopted by nearly every American museum. MoMA was not the first museum to advocate 20th century art (Duncan Phillips and Alfred Barnes got there first), but it was the first that did not reflect one person’s taste, and it was the first to systematically advocate modernism. Its first and most influential director, Alfred Barr, was a minister’s son who preached the modernist gospel with a devotional zeal. His goal was to make converts, and an essential part of Barr’s proselytizing program involved exporting aspects of MoMA’s collection to libraries, department stores, society clubs, and the few museums then willing to accept the “heresy” of modernism into their galleries.

Before abandoning his idea of a rotating collection, Barr imagined MoMA art holdings as “a torpedo moving through time”: stealthy, subversive, and packing a punch. But permanent collections are, by design, conservative and exclusionary. To see MoMA’s best holdings on the road is thus to be constantly reminded of the importance of context, and of choices made. The Heroic Century (already a very large show) should not be any bigger, but it is important to remember that MoMA’s canon, as expressed here, is a narrow one, stripped of the “good use” aspects (design, graphics, architecture) that Barr considered so fundamental to the museum’s mission. A film program does convey MoMA’s pioneering interest in that most fundamentally 20th century medium, and a supplemental exhibition assembled by Anne Tucker from the MFAH’s Heiting collection handsomely and incisively establishes the breadth of recent photographic trends. But even a cursory comparison between MoMA’s collection highlights handbook and The Heroic Century catalogue crystallizes the big difference between MoMA on the road and MoMA at home.

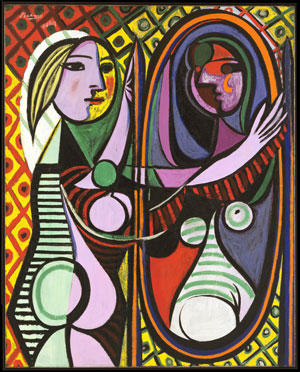

Painting was Barr’s primary focus, and it shines through this exhibition, from the early masterworks by Van Gogh, Cezanne, and Picasso that initially established the museum’s credentials, to the American watershed of Abstract Expressionism, to the large selections of paintings by Guston and Richter that, concluding the show, function as strongly declarative sentences about the continued viability of painting. There is much good sculpture here, but only two lovely drawings, by Braque and Picasso, cameo the art of collage. After so many shows couched in terms of chair rails and color schemes, the MFAH galleries are uncharacteristically neutral. White boxes shorn of historicizing color combinations or architectural adornments, their layout continuous rather than subdivided, they have never looked better.

New York Times critic Michael Kimmelman, speaking at the Shartle Symposium shortly after the show’s opening, recast MoMA’s founding as part of the progressive women’s movement, but his story (most of the founders were women) is contradicted by the paucity of women artists (9 of 110) included. There are many fine depictions of women, but there is no Frida Kahlo or Kay Sage, nor any Lee Krasner, Jay De Feo, Chryssa, or Grace Hartigan (all championed by MoMA’s legendary curator Dorothy Miller). Influential artists of more recent generations, like Lorna Simpson, Annette Messager, or Kiki Smith (all well represented in the museum’s collection) are similarly omitted. This transition, from women as artistic subject matter to artistic creators, is one of the big stories of modernism that The Heroic Century does not accurately convey. I would point out a few other anomalies. Joseph Beuys, the most influential postwar European artist, is nowhere to be seen, and given the prominence accorded to Robert Rauschenberg, the absence of his European antecedent, Kurt Schwitters, seems odd. From the point of view of this show, art is still video free. MoMA owns video installation (Bill Viola, Gary Hill) that would have counterbalanced their painting predilections while accurately reflecting the emergence and maturation of a new medium during the 1970s, 80s, and 90s.

These are the kind of things you find yourself thinking as you walk through the main floor galleries. Eyeing an abundant lineage installed thematically so as to echo the museum’s own exhibition history, you find yourself in dialogue with it. MoMA chief curator John Elderfield has admitted that the artworks are installed rather more closely than his museum’s standard, but this proximity has the salutary effect of refreshing the collection, encouraging a reading of the assembled artworks as one large compare-and-contrast essay. MFAH curator Barry Walker has emphasized this in productive, even striking ways with an installation that rethinks the contours of the canon. I remember no juxtaposition of American and European social realists from my many MoMA visits: here they reside cheek by jowl. There is great virtue in seeing Beckmann’s triptych Departure opposite contemporaneous works by Hopper, and adjacent to Balthus’ The Street and Bonnard’s Nude in a Bedroom. Similar conflations of disparate styles (it is always a shock to be reminded that Kandinsky’s non-objective paintings predate Monet’s panoramic, late-period Waterlilies) enliven many of the main floor galleries.

. 1931. … Fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon”]

The Heroic Century loses focus as the action shifts downstairs. By the time you have transited the obligatory show-specific gift shop and shuttled down the escalator to pick up the thread in the large downstairs gallery, the taut, breathless pace has jumbled. Especially toward the end of the exhibition, multiple examples by individual artists (Richter, Guston) serve as placeholders for an art world that has become, comparatively, as broad and wide as the Mississippi. Clearly, any selection would be akin to dipping one’s toe in that huge river. Consistent with MoMA’s longstanding difficulties in dealing with recent artistic activities, very little room has been accorded to the revivalist or lateral movements, characterized as neo— or post—, that dominated the 1980s and 90s. Most living artists are represented by their earliest work, and this sometimes skews perspectives. This accurately reflects MoMA’s longstanding diffidence (Alfred Barr was an ambivalent promoter of American contemporary art), just as it reemphasizes the inherent bias toward history that is the inevitable result of maintaining any collection. Does the MoMA canon still pertain? You bet it does, and arguing back at it even as you admire its breadth and depth reveals as much about the position of you, the viewer, as it does about the show. In any case, it will have to do while the world of art, like the world at large, awaits a new guiding principle that will motivate a rebirth of wonder.

All images appear courtesy the Museum of Modern Art and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Christopher French is an artist and writer living in Houston.