There is a show of Ikat fabrics on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston that I think you should see.

I say ‘should’ mostly because it’s been a crazy few weeks. I’m speaking of course of the circus in our nation’s capital. Right now I mention ikats and you could be forgiven for thinking, textiles? Isn’t there some important art on view somewhere? It’s true that this is just some old clothes, worn by people long since dead and forgotten. Presumably nobody made these things for the reasons we typically admire in artists: out of an earnest desire to effect social change for the good; or in a spasm of passionate, soul-baring emotion; or to strategically further one’s art career. The artists who made these things made them to give pleasure. They figured out remarkable new techniques to make them. And they came from a part of the world that, like all parts of the world, is far more interesting than the two-dimensional caricature that lives in the Western imagination.

More than anything, Colors of the Oasis: Central Asian Ikats is exactly the kind of show that can blowtorch away any calcified, received ideas around the kind of art that you should be looking at, the kind of art that’s any good and that’s important. If nothing else, you might question whether you need any more disposable clothing from fast fashion retailers.

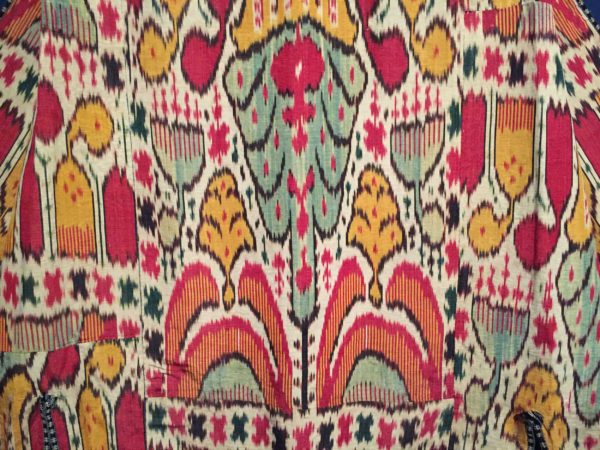

For one thing, ikats are wild. They feature vigorous, linear abstraction, especially when compared with the sentimental floral bouquets and paisleys of European textiles from the same era. In his essay for the catalog, Andrew Hale argues that ikats marked an evolution towards secularism, and influenced the Suprematism that emerged around the time of the Russian Revolution: “The energy and abstraction of Central Asian art was much admired [and] served as an inspiration… as African art did for their European counterparts.”

Meaning Ikats are to Malevich as West African statuary is to Picasso.

As Hale points out, if the fundamental goal of Islamic art is to give order and meaning to an infinitely chaotic universe, ikats may serve that goal through pattern and repetition, but they veer off dramatically from the kind of controlled restraint found in most Islamic art. There are no niches here, no borders. Like jazz musicians, ikat designers riffed on the same motifs over and over, resulting in endless loose variations on classic designs.

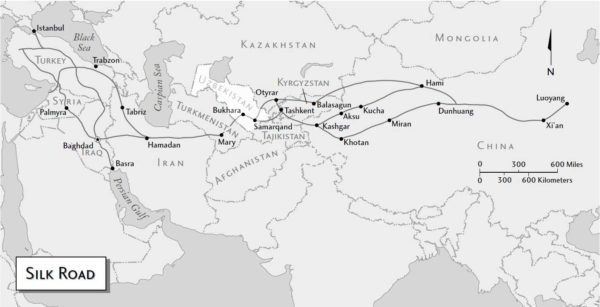

The golden age of Ikat fabrics was the 19th century, when almost all of the objects in this show were made. They mostly come from present-day Uzbekistan, in that Central Asian pocket of former Soviet republics squeezed between the countries we typically hear about: Russia, Iran, Afghanistan, China.

The drabness of war coverage we’ve been watching from this region since the early ’90s (people in earth-toned robes; our soldiers in their desert fatigues; barren landscapes; the Taliban not wanting anyone to have any fun) might suggest that whatever design the region could muster would be similarly beige, monochromatic and joyless. But ikats are wildly colored, a truer reflection of the Central Asian landscape, as one essay in the exhibit’s catalog describes, of blossoming fruit trees, flowers growing on clay rooftops, and igniferous sands.

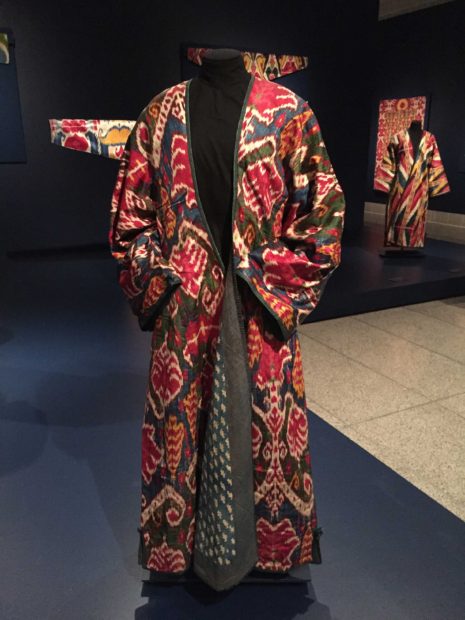

The exhibition is handsomely installed in the downstairs gallery at the MFAH across from the café. (I’ve grown fond of this no-frills gallery; its humane scale makes it one of the more successful spaces in the Beck building for looking at art.) Following a trend in exhibition design, dark indigo walls and spot lighting set off the bright robes to good theatrical effect. In short, it’s a beautiful show of extraordinarily fine ikats. I almost wish the curators would include some lesser examples so that people could see a side-by-side comparison of what’s worthy to be included in a museum show and what is not.

These robes weren’t easy to make. It turns out ikats are one of the more technically challenging of all traditional fabrics to create. The design is dyed into the yarns before the fabrics are woven, which results in the “bleeding” edge of colors in ikats. The design must be completely plotted in advance, and the yarns, which are much longer than the finished piece will be after weaving, are tied and re-tied to be dyed in a predetermined sequence of colors that will create the final design. That design only emerges when the fabric is woven.

A dozen specialized craftsmen were required to create the garments included in this exhibition, including silk cultivators, spinners, designers, dyers, weavers, finishers, and tailors. Such a complex operation was the culmination of centuries of luxury fabric production. You have to admire the flowering of human ingenuity that developed this art form, which is distinct from any textile production preceding it. Of course, that ingenuity flowered because the 19th century was a period of relative stability and peace along that section of the Silk Road.

When society goes to hell, the arts do too. You don’t get lush objects like these from a war-torn region; and the upheavals of the 20th century resulted in a huge decline in the quality of rug and textile manufacture throughout the Middle East. During the 19th century, Bukhara was like Paris for the Europeans. But under the Bolsheviks, families in recently-conquered central Asia were stripped of their personal wealth, including their textiles, and guilds and workshops that specialized in making the fabrics were forced to close. Ikat robes, which during the 19th century had become the fashion in Russia for what we might describe as loungewear, especially among intellectuals and artists, were seen as decadent manifestations of the corruption of the Russian aristocracy and were shunned. And the competition from factory-made fabrics all but wiped out handmade production.

Now that we have a new 1% and a newfound appreciation for all that is artisanal and handmade, there has been a resurrection of ikat production in the past 15 years. Much of the current production reproduces the most luxurious mid-19th century ikat patterns, and is now funneled to Western couture houses.

Oscar de la Renta’s 2005 spring collection is widely credited with launching the current fad for ikat fabrics in fashion and home decor.

We need peace and prosperity to have beautiful things. And as unpopular as the notion might be right now, we also need rich people to patronize and foster the highest human ingenuity of artists and craftspeople (even if we grouse that rich people usually buy the wrong art). It would be easy to get hung up on the socioeconomic issues around these luxury fabrics because that is the dominant narrative of the day, but to my original point—in the best and most idealistic sense—looking at an exhibition of objects like these helps one comprehend, as the catalog says, “the spirit of this land and its people.” Central Asia is far more than the dark heart of cruelty and ignorance that festers today in the imagination of the West. The same spirit of pleasure that resulted in these objects lives on. Discovering, enjoying, and making peace with that spirit seems something worth fighting for.

Colors of the Oasis: Central Asian Ikats is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston through June 4, 2017.

9 comments

Rainey- you’re right, this show is amazing.

Can’t wait to see this!

Business as usual w/the ersatz (née silver-spoon-in-the-mouth set)… who knew? a show about artisan craft… the rarefied object has been there all along… just not to such a degree as to merit a big splash under the guise of cultural enrichment, generally. But never you mind, they always have a way of creating a buzz in order to capitalize those investment portfolios without having to enrich those pesky artisans.

Fortunately there’s a nascent revival among artisans who produce this work, perhaps they stand to be enriched.

they already are… just not in the moneyed sense. viva the mckenna bros. for enlightening us all.

We also have a local guild that works with the institutions in demonstrating how these art peices are made.

More early 20th-c. color photographs of Russia by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky:

https://avax.news/educative/Early_20th-century_Russia_in_Color_Photos_by_Sergey_Prokudin-Gorsky.html

Thank you, Rainey. Seeing your comment come up on this earlier piece, I had to look twice at the date of the color photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky. Thanks for taking me down an unexpected rabbit hole this morning, especially after such a challenging week. These images are truly amazing.

Glad it was fruitful. Challenging week indeed (we’re speaking of the Great Freeze of February 2021).

Nobody but me probably would remember that I had used that photograph for this obscure article from 4 years ago, so I figured I’d add it in the comments. More grist for the mill, more serendipity, more web of interconnectedness…