Constructivism in Latin America provided fertile ground for a plethora of different movements, proposals and ideas from the 1930s onward as seen in Constructed Dialogues: Concrete, Geometric, and Kinetic Art from the Latin American Art Collection, currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (only until January 6, 2013). The rich traditions of surrealism and expressionism within Latin America have often overshadowed the more contemporary constructivist dialogues, and more importantly the legacies of constructivism. After taking a walk around the Constructed Dialogues exhibition, it makes one think how constructivism gave birth to new artistic dialogues and forms within different countries throughout Latin America and what came next on a regional level. Here’s a short list of a few random legacies of constructivism in Latin America which come to mind after looking at the Constructed Dialogues exhibition: The School of the South (Uruguay), the Neo-Concrete Manifesto and Grupo Frente (Brazil), Gego’s Drawings Without Paper (Venezuela) and the Avant Garde Artists’ Group (Argentina).

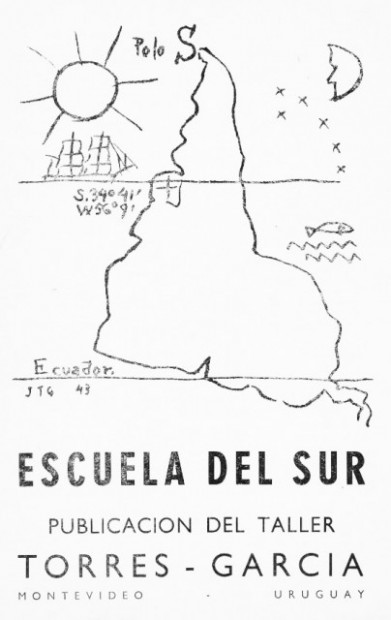

Joaquín Torres-Garcia, The School of the South and El Taller Torres-García (TTG)

The School of the South is a manifesto published in 1935 by Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-Garcia, considered by many the father of Latin American Constructivism. In it he proclaimed, “Our North is the South” and opened with an inverted map of South America, with the tip of Patagonia pointing south, at the top of the page. By inverting the map, Torres-Garcia was announcing the beginning of a new era in Latin American art and calling on his fellow Uruguayans to be conscious of their own culture, rather than the culture of Europe. He later launched El Taller Torres-García (The Torres-García Studio, or TTG) in 1943, a workshop school where artists worked collectively on murals, architecture, sculpture and crafts, often in conjunction with writers, musicians and performers. TTG launched the careers of many artists including Augusto and Horacio Torres, Julio Alpuy and Gonzalo Fonseca. Today, the legacy of this movement is for the most part conceptual rather than aesthetic, but from the 1940s on, Latin American artists turned to Torres-Garcia and his School of the South for guidance and legitimacy in theoretical, aesthetic and ideological concerns.

“It must have been an amazing place to study. The pages from Torres-García’s notebooks, with their collages of Egyptian, Greek, Indian, pre-Columbian and European art, indicate the invigorating breadth of his interests, and his call for a Latin American art to be ‘created from the bottom to the top’ surely quickened the pulse of the young people who came to him.”

– Holland Cotter, The New York Times, December 4, 1992

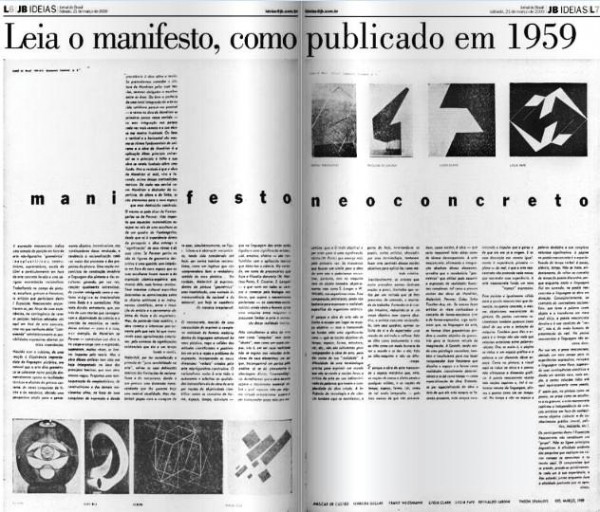

Neo-Concrete Manifesto and Grupo Frente

Decades after the The School of the South, Manifesto Neoconcreto (Neo-Concrete Manifesto) was published in the Sunday Supplement of the Jornal do Brasil newspaper in 1959. Criticizing the Brazilian Concrete Art movement which dates from the early 1950s, the Manifesto Neoconcreto denounced the dogmatism and excessive rationalism that led to Concretism and instead looked for a more integrative art which framed a corporeal knowledge. The manifesto signified the further division of two well known Brazilian centers of art making—Grupo Frente (Front Group) in Rio de Janeiro and Grupo Ruptura (Rupture Group) in São Paulo. Group Frente later made rich artistic contributions in their interests in physicality, sensorial knowledge and bridging the divides of art and life.

“We do not conceive of a work of art as a ‘machine’ or ‘object’ but as a ‘quasi-corpus’; that is, a being whose reality is not exhausted by the external relationships of its elements; a being that can be deconstructed into parts for analysis but can only be fully understood through a direct, phenomenological approach. We believe that a work of art surpasses the material mechanism on which it rests, but not because it has an extraterrestrial quality: it surpasses it by transcending such mechanical relationships (which is the aim of Gestalt) and create, in and of itself, a tacit meaning that emerges for the first time.” – from the Neo-Concrete Manifesto (1959)

Nildo, of the Mangueira samba group, wearing one of Hélio Oiticica’s Parangolés (1964) Rio de Janeiro. Oiticica was a later member of Grupo Frente.

The Art of Meaning and Grupo de Artistas Argentinos de Vanguardia (Avant Garde Artists’ Group)

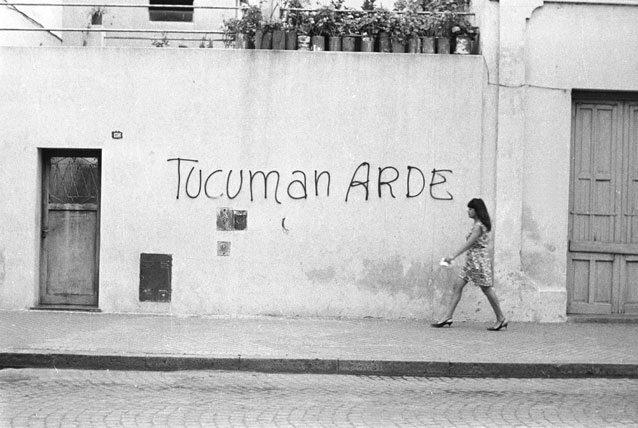

León Ferrari presented his manifesto El arte de los significados (The Art of Meaning) at the Primer Encuentro Nacional del Arte de Vanguardia (First National Conference of Vanguard Art) in Rosario, Argentina in 1968. In it he writes, “Art is not beauty or novelty, art is effectiveness and disruption…” These thoughts would be further echoed in the actions of the collective Grupo de Artistas Argentinos de Vanguardia (Avant Garde Artists’ Group), who would later organize pivotal collective exhibitions and actions such as Tucumán Arde (Tucumán Is Burning) and Experimental Art Cycle in Rosario.

Rosario Group, Tucumán Arde (Tucumán Is Burning) (1968) Publicity Campaign (2nd Step) Graffiti. Archivo Graciela Carnevale, Rosario, Argentina

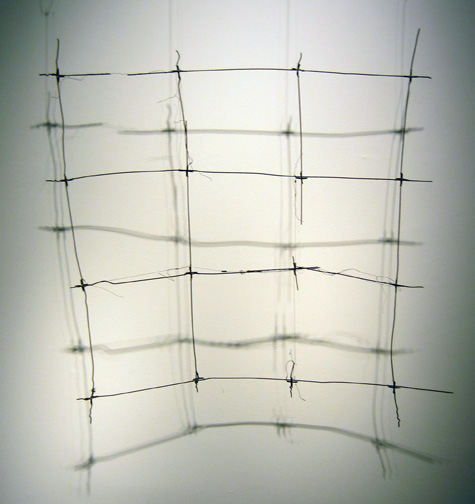

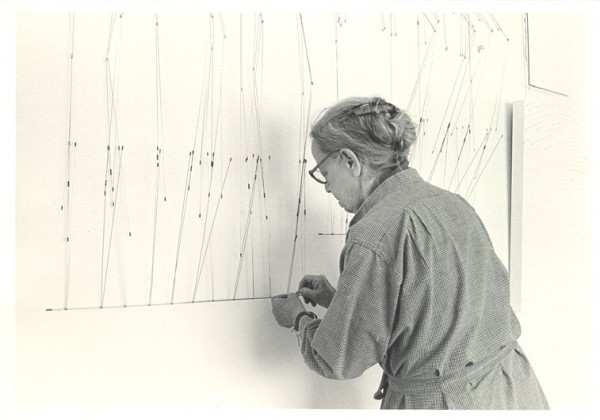

Dibujos sin papel (Drawings Without Paper)

An especially unique voice in the legacy of constructivism is Gertrude Goldschmidt, also known as Gego. Gego’s work stood out in Venezuela’s dominant modernist visual discourse of Cinetismo (Kineticism) as seen in the work of Jesús Rafael Soto and later in artists such as Carlos Cruz-Diez. Instead, her treatment of line and the grid was more precarious and less rigid. Beyond optical illusion, Gego explored permanence through her take on the line and movement beyond the grid. From the late 1970s and ’80s she developed a series entitled Drawings Without Paper.

“Sculpture: three-dimensional forms of solid material. NEVER what I do!” – Gego

2 comments

“Decades later after the “The School of the South” Manifesto Neoconcreto (Neo-Concrete Manifesto) was published in the Sunday Supplement of the Jornal do Brasil newspaper in 1959.”

Can you imagine such a thing happening here and now? That a major newspaper would consider the ideas of artists important enough to let them publish a manifesto in their pages is unimaginable now. Art now exists in its own little bubble, coming into contact with the broader public on when auction results are announced.

Robert – To this day, most daily newspapers in Latin America have cultural supplements where artists and poets are given wide rein to share their opinions, present their thinking and do critical work.

So while it is hard to imagine major newspapers in the capitalist belly of the beast here in the US publishing artistic manifestos, there are long traditions of just this happening south of our border with Mexico.

Best, JP