In Texas, we are a direct physical and cultural liaison to everything south of us — which, frankly, is a lot. We tend to focus on our Mexican neighbors because of our mutual border close by, but just below that, Central America forms the slim waist in the contraposto of the Americas Proper.

In Texas, we are a direct physical and cultural liaison to everything south of us — which, frankly, is a lot. We tend to focus on our Mexican neighbors because of our mutual border close by, but just below that, Central America forms the slim waist in the contraposto of the Americas Proper. Why do we tend to treat it as a bottleneck in our cultural relationship, cutting off connection up and down the longitudes?

Some recent museum exhibitions have had a major impact on scholarship and how we look at Latin American art, including Mari Carmen Ramírez and Héctor Olea 's Inverted Utopias: Avant-garde Art in Latin America at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and Retratos: 2000 Years of Latin American Portraits at the San Antonio Museum of Art with its four curatorial collaborators: Marion Oettinger, curator of Latin American art at the San Antonio Museum of Art; Fatima Bercht, who until recently was chief curator at El Museo del Barrio; Carolyn Kinder Carr, deputy director and chief curator at the National Portrait Gallery; and Miguel Bretos, senior scholar at the National Portrait Gallery . In addition, the opening of the Blanton Museum of Art in its new location pulls back the curtain on important changes in how we display art. Gabriel Pérez Barreiro puts his foot down on tradition and desegregates Latin American art from its traditionally separate wing, integrating it with the rest of the Blanton's modern art collection overseen by Annette DiMeo Carlozzi.

In this article, I weave together the voices of Latin American art specialists from interviews I conducted with Pérez Barreiro of the Blanton, and three curators from Retratos — Oettinger, Bercht and Bretos — in order to construct a discussion on the past and present of Latin American art history. Each interviewee sheds light on collecting, learning, producing, and classifying Latin American art and its related studies. In addition, the symposium Sin Título that took place as part of the Blanton's celebratory re-opening provided the opportunity to hear an international panel talking about curatorial practices at the Tate Modern in London, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Christie's Auction House, and the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes in Rio de Janeiro. Their ideas too are woven into the discussion.

If you know what Latin American Art is, please raise your hand.

To begin with a simple fact, America's Euro-centric education barely footnotes Latin American art in its discussions of major movements and influences, whereas in the countries of Latin America, students learn about national art alongside art from Europe and America. Both Fatima Bercht and Gabriel Pérez Barreiro commented on that unfortunate paradigm, the same one that causes Latin American artists to be considered derivative in this country rather than as instigators of new creative trends, simply because we fail to fully investigate cross-cultural influences and the movement of artists over the globe.

Exhibit 'A' of this bias is Edward Lucie-Smith's statement that appeared as late as 1976 in Late Modern: The Visual Arts Since 1945 : "Similarly, the various kinetic artists…are for the most part expatriates; national exhibitions, brought to Europe from various South American countries, have done nothing to suggest a new idiom, significantly different from that used by artists in Europe itself, or in the United States." In fact, the place in the canon of neo-concretism from Latin America and minimalism from the United States is being seriously reevaluated in exhibitions like LACMA's Beyond Geometry: Experiments in Form 1940s – 1970s. Learning art history from just one direction is like believing that the earth stands still and everything revolves around it.

So, raised in Brazil as she was, Bercht learned about mid-century art from America and Europe, as well as her own national idioms. When she went on to Columbia University in New York, however, she found the opposite quite untrue. (To be fair, Bercht also mentions how uninterested America was in its own art until we started rising in importance after World War II with the New York School.) This rebirth had many causes, not the least of which is the influence of Latin American émigrés like Roberto Matta, Arshile Gorky who heavily influenced artists like and Robert Motherwell, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, who was briefly but importantly Jackson Pollock's teacher.

According to Bercht, politics often creates gaps in collections and histories, which was particularly so during the era of rabid anti-Communism: "What is presented [of Latin American art] in the United States is one reality. A wave came with exhibitions during the late 1930s, then a wave of exhibitions in the 1960s, but then at the beginning of the 1970s Latin America became almost an impossible subject because of the political situation. Now since the 1990s it has been growing again. The creation of curatorial niches is also growing for Latin American and Latino art." In encyclopedic museums, these collections encourage the appreciation of distinct cultural histories — which in turn creates interest and funding for more collecting. These collections, like collections that feature African-American artists, can also serve to segregate, perhaps even ghettoize, works of art. This traditional curatorial practice ignores the fact that art history is actually quite fluid, a good example of which being the modernist era between the two World Wars, with its heavy cross-cultural interest between Paris and Latin America. But more about this later…

Latino art is not Latin American Art

What we are often attuned to in Texas is the American art category of Latino (or Chicano, or Hispanic) art and identity. Its sub-definitions can get rather slippery, and even those at the heart of the matter often disagree on use and meaning. In practical curatorial terms, however, does a Hispanic last name make you just as much Mexican as American? What if you have never been to Mexico or don't speak Spanish? What determines that you should be grouped in exhibitions under the rubric of a "Latino" artist?

Latin American art, while it sounds similar to "Latino" art, is a separate subject and we should beware our too easy groupings. While there are organizations, symposiums, and archives that lump together Latino and Latin American art, it is important to know the difference between the two. In fact, Pérez Barreiro, debunks their grouping together, as well as simple exhibition themes such as "New Art From Mexico," and is careful to avoid it in his own curatorial practice.

The opposite would be to take someone who has a drop of Latin blood in them, or who speaks Spanish, and say, "You belong over there because you're different and your culture has nothing to do with ours, and so we'll look at it in almost a National Geographic way. We'll be nice, and we'll be generous, and we'll feel good about ourselves, and we'll put Spanish labels up." …And what happens is, as soon as you say the words "Latin America," people think "Latino," they think underserved — they think of it in political terms. And so you're already sort of outside the museum. They never think maybe we should reevaluate our definition of American art because some people have been living here for several generations. San Antonio is a great case where, what's the point of [assembling] the artists who might be Hispanic but don't speak Spanish…You can't essentialize it from a label. No, [the artist is] what he is, and you go figure it out. You can say you're one thing, but it's at the expense of all the other things you are, too.

But many institutions conduct their missions that way because it is standard practice. The Alameda Theater in San Antonio presented the exhibition ¿ Seis Who? last summer, garnering questions about the curatorial choice of six local artists of Hispanic descent whose work is very stylish and contemporary, and why it constructed a picture of Latino culture rather than simply American. It's difficult, though, when you try to measure and qualify cultural experiences. It must, in the end, be left to the artists to consider the kinds of issues their work deals with and to what kinds of exhibitions they belong.

Going further back to basics, the Smithsonian's Miguel Bretos touches on the history of the relevant terminology.

First, Latino studies. I do not unquestioningly accept the term 'Latino.' It is a malapropism, the product of misguided notions about the ownership of identity and its definition. In effect, the choice of "Latino" versus 'Hispanic' (a term I prefer although also unsatisfactory) was imposed by a Hispanophobic, ‘indigenista' sector of the U.S.'s Latino/Hispanic intelligentsia. Why? In order to put distance between us and white, European, colonialist Spain…We had to become something of our own choosing, and so we became Latinos. That is, we became a spin-off of Latin America. And Latin America? Well, consider that the term 'Latin America' was literally invented by Frenchified Latin American intellectuals during the latter part of the 19 th century.

So, then, where is this place known as Latin America?

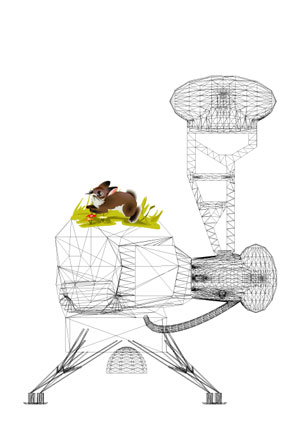

In a sense, it doesn't exist. Only several large, independent countries in that region exist rather than one large cultural mass and, even within those, there is a wide cultural gap between rural and urban communities. Simón Bolivar, ‘The Liberator,' believed in a confederation of Latin American republics. He even went so far as to propose one in 1926 at the Congress of Panama only to see it fall apart. South America's version of 'I think, therefore I am,' might be, 'There are national armies. Therefore, there are countries.' Cuauht é moc Medina, Associate Curator of Latin American Art for the Tate, London, pointed out at the Blanton's symposium that, while these armies circumscribe our ideas of place, it is often easier to associate oneself with a failed utopia than align with the real governmental structure. This raises questions about place, country, culture and ideals that we can bend to our will, in the face of accepted lines on a map.

These questions of identity relate not only to artists, but to curators and viewers as well. Marion Oettinger, director of the San Antonio Museum of Art, is also head of that institution's Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Latin American Art. His credentials are impressive, and as an anthropologist by training, he has a nuanced world view:

"I have never felt stymied by being a non-Hispanic scholar," Oettinger says. "I am fluent in Spanish and have lived and worked all over Latin America and Spain for over thirty-five years. I have spent years working in isolated indigenous communities as well as in formal halls of Latin American academia…This having been said, I am fully aware that I deal mainly in 'perspective' rather than 'truth' and to approach the truth more closely, I must add my perspective to those of others with entirely different histories, educations, and biases."

Ironically, while this article is about Latin American art, the more one delves into its main characters, the more individuality and immersion matters over nationalistic labels.

Painting art history's portrait — if only it would stand still.

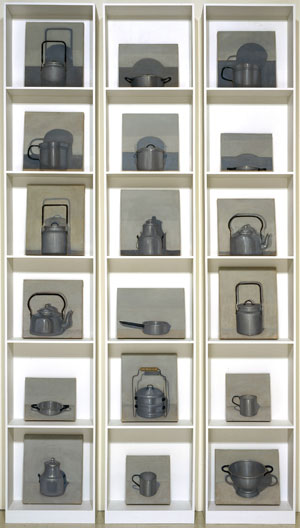

Oettinger's special museum collection is immensely rich in objects, including the history of Latin American handcrafts, rare codices, folk art, and Pre-Colombian portraits. Oettinger says that its mission is to 'celebrate the richness of Latin American art and to alert those of Latin American descent to the importance of their artistic heritage, and to introduce those not of Latin American descent to the extraordinarily long art history of that part of the world and its relevance to the U.S. today.'

This is also the main mission, it seems, of Retratos , for which the collaborators traveled to more than 15 Latin American countries in search of rare, never-before-seen or simply crucial works of portraiture. And when taking the long, long view into art history, the portrait seems an important device. Bretos would have loved to see it done ten years earlier, but since it is the first show of its kind he of course says, 'Better late than never.' For his part, Oettinger describes the project at hand thusly:

Realizing that a pan-Latin American exhibition on portraiture had never been attempted, I and my colleagues thought it would be good to do a broad introductory treatment of the subject through time and space. Our hope was that, subsequently, other curators, art historians, etc. would be sufficiently excited about particular parts of our overview so as to organize in-depth treatments in the future — [subject such as] portraits of crowned nuns in Mexico; death portraits in Latin America; miniatures, etc. We also wanted to use such a broad treatment of the subject to reveal common influences and trends throughout Latin America. This certainly became apparent, especially during the Colonial, Independence, and Modernist periods. Representation was light on pre-Colombian art since we wanted mainly to show that portraiture was highly prized among native cultures prior to the arrival of Europeans.

Works from the Viceregal era in South America deal directly with the attempt to assimilate indigenous culture into Renaissance-era European culture, particularly through Jesuit missionaries. Here, the match was struck that started the conflagration of identity issues still raging today. The subsequent Independence-era works include iconic faces, like Simon Bolivar's revolutionary portrait from the early 19th century.

Shaking up our assumptions along the way was a goal of these curators. Bretos, for example, mentions American myth versus history, like the fact that Maria Jimenez de la Cueva y Melendez is the first fully documented person in what would become the U.S., and not the European-descended Virginia Dare, as is commonly stated. Finding out more about the characters involved changes our concept of history. This really is the influence that exhibitions like Retratos can provide — not necessarily groundbreaking themes in art or the use of new media, but the curatorial search for what is missing. Putting new pieces in the puzzle changes the way it looks.

What has Diego done for me lately?

The integration of art at the Blanton has its roots. Most notably, Alfred Barr, founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, planned for an installation where Mexican and American avant-gardists were to be hung alongside their European counterparts who were in much larger standing. And in 1931, only two years after the museum's founding, MoMA held a wildly successful exhibition of Rivera's work that was visited by a whopping 57,000 people. Clearly the interest was there for Mexican modernism, and often these discussions pivot around Rivera. Collections, too, like the Marion Koogler McNay's, often begin there. Diego Rivera's reputation was huge, but we can't stop there. Nor can we stop with his wife Frida Kahlo, whose reputation has probably eclipsed her husband's, in large part by post-modernism's interest in feminism. These are highs that should lead to harder things.

Bercht explains that Barr intended to use Mexican modernism as an entrée to the acceptance of the American avant-garde: "In the 30s and 40s, Mexicans were coming here. First Alfred Barr understood it was the presentation of Mexican art that would help him present American art. There were magnificent murals being painted and important work being done in Mexico. Barr was collecting modern Latin American art, especially from Mexico, but also Brazil and Argentina. It was going to be used [to look] at modernism as an international phenomenon. This ties to what Gabriel is doing at the Blanton, inserting the material the way Barr wanted to."

Following this success, however, gaps began to appear in MOMA's collection over the years, often due to political issues. This is still a collector's issue today (and is the reason Retratos missed out on the finest cache of Cuban portraiture in the world). But politics aside, the size and scale of Latin America lent itself to widely different art practices that were simply challenging to follow from afar. Unfortunately, rather than improving, we let the 20 th century go by as if travel and quick connections had barely come into existence since Barr's time.

Lately this is changing with exhibitions like LACMA's Beyond Geometry and the MFAH's Inverted Utopias. Pérez Barreiro offers some thoughtful perspective on the latter exhibition:

Inverted Utopias was the first real, comprehensive overview of the Latin American avant-garde, and in that sense it was hugely important. There had only been fragments of that outside Latin America, the presentation of that material. It's been seen in Latin America before. It's only the in States that is has been — well, there had only been little bits of it within a much broader framework. What I questioned in that show is the central premise of it — the idea that all of the Latin American avant-garde art is an inversion of the European avant-garde. I don't think the European avant-garde is all in one direction.

We are making strides, and as these themes get worked out we will continue to reveal new ideas. And maybe, just as learning a foreign language's grammar teaches about one's language, we will actually learn more about European art history by studying Latin American art.

Having a great time in Paris. Wish you were here…

As mentioned, the Blanton is doing way with traditional artist labels. Instead, they will expand on simple country of origin and integrate the cosmopolitan nature of many avant-garde artists' lives with a chronological list of cities in which they lived and worked. Walking into the first room of the 20th century collection,

Pérez Barreiro explains:

Everything you see here is a collaboration between me and Annette [Carlozzi].' 'We started at this point with a more South American focus, although this work was produced in Paris, this one in New York, and this one in Italy. This was I think the most important thing we did because we had artists who were classified as — for example, Joaquín Torres-Garcia was Uruguayan — and I think, ‘Yeah, but he left with he was sixteen and went back when he was 70, so is it fair to talk about him with just one adjective?' Therefore does it make sense to talk about him in terms of Latin American art?

So by taking off the adjective that says where they were born, we moved it to the unit of the city so it says exactly where they were living and working at any particular point. So for example, the fact that he was working in Paris in 1931, when MoMA reinstalled its collection and sort of integrated those works. And when Holland Cotter wrote his review in the New York Times , he said, ‘Finally they've acknowledged non-Western Art.' And I think, ‘Well, it's not non-Western, and in the photograph you had Torres-Garcia next to a Mondrian. Now, if you look at those labels and you see one of them was Uruguayan and one of them was Dutch, you don't get the story. If you see both of them were in Paris you get, ‘Okay, these artists were contemporaries, these are artists that were in dialogue with each other as opposed to one imitating the other.'

In Carlozzi's introduction to the Blanton's symposium Sin Título, she projected images side by side as they are hung in the collection. She acknowledged the risk of pairing up pictures — that some may see it as simply a game of matchy-matchy. But then again, there are artists solving similar formal problems across the globe and often, as with Torres-Garcia, these multi-cultural artists congregate in centers like Paris and New York and are directly influenced by each other.

Later, Luis Enrique Pérez Oramas, Adjunct Curator at MoMA, talked about some of the criticism received, and not received, by various hangings at his museum. Some visitors had a hard time seeing Pablo Picasso, king of the Western canon, shown next to so-called 'lesser' artists, like Venezuelan artist Armando Reverón, even when they had many little-known things in common. Rever ó n studied in Barcelona from 1911-15 and Picasso's father was his teacher — and that's just the beginning of their connection. Yet according to Oramas, no one questions it when an El Greco is hung beside one of his Spanish contemporaries, despite the fact that his work was years ahead of its time and had major stylistic differences from the majority of his peers.

Fin

It is an exhilerating opportunity to learn from exhibitions that rewrite history, and to hear curators of this caliber work out our cultural kinks. It just shows that there is important new work for our generation to do, and even those topics that have been written about ad nauseum still may have a second wind.

Holland Cotter, “NEW MIX; Outside In: Non-Western Art Moves Into the Main Gallery” New York Times, March 30, 2005, WednesdayLate Edition – Final, Section G, Page 1, Column 2, 2923 words

Images courtesy Blanton Museum of Art and San Antonio Museum of Art.

Catherine Walworth is an artist, writer and curator currently living in San Antonio.