Anahuacalli, photograph of exterior with potted marigold flowers for Day of the Dead, 2017, © Ruben C. Cordova.

This is a guide to altars and installations in Mexico City. We begin with Anahuacalli, Diego Rivera’s enormous Maya Revival/Gothic/Deco structure fashioned out of volcanic rock formed by the eruption of Mount Xitle. It was designed to house Rivera’s collection of more than 50,000 pre-Columbian objects, and also to serve as a studio and a cultural center. Rivera began working on it in 1942. He corresponded with Frank Lloyd Wright about design issues, but had only completed the first floor when he died in 1957. The architect and artist Juan O’Gorman, who was Rivera’s friend and collaborator, supervised Anahuacalli’s completion. It opened in 1964. Anahuacalli set the standard for Day of the Dead altars, particularly after 1968, when the Linares family was employed to make papier-mâché skeletal figures in honor of the Mexico City Olympics. Over the years, the Linares family has crafted vast armies of inimitable skeletal figures and elaborate stage sets specifically for Day of the Dead. These works by the Linares clan also appear at the Frida Kahlo Museum and the Dolores Olmedo Museum.

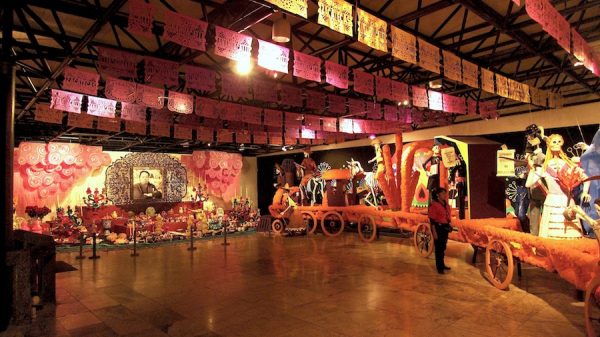

In 2012, the altar, held in a subsidiary building, was comprised of three parts: a traditional altar dedicated to Rivera (left), with a profusion of extraordinarily crafted bread, foodstuffs, and folk art; a literal train manned by Linares figures representing key episodes in Mexican history (primarily the Revolution of 1910); a wall of skeletal tableaux (out of sight on the right). In addition to amazing visuals, the best Mexican altars also have powerful scents, emitted by fruit, candied foods like squash, and cooked food including mole sauces. No wonder they can attract the spirits of the dead!

This is a traditional sand painting of Frida Kahlo (dressed in a Tehuana outfit). She is kissing Diego Rivera, who sports a blue beret. The small skeleton on the left represents the child that Kahlo could never bring to term. This sand painting was in the basement of another subsidiary building in Anahuacalli. I took this picture while hanging over the balcony on the ground floor.

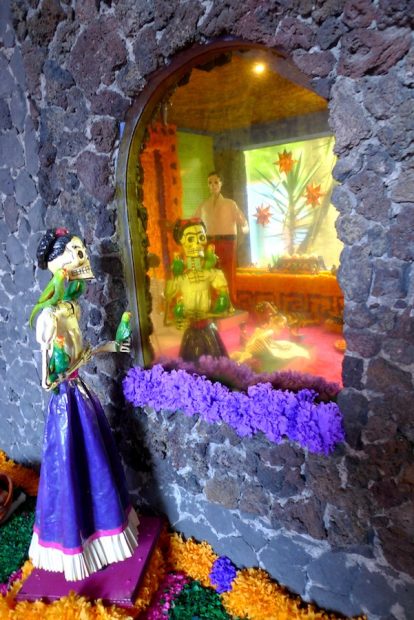

The Frida Kahlo Museum is a “must-see” historic space. It maintains the house’s original furnishings, including an extensive collection of folk art. The museum owns many works by Kahlo and Rivera, though most are not among their most important paintings. This photograph shows Kahlo (with her parrots) looking in a mirror, which reflects a portion of the altar that includes Rivera. A recent museum expansion made room for a display of Kahlo’s clothing and objects that had been in storage since her death. Nonetheless, space is at a premium, so the altars here are not very large. The Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky initially lived here when Mexico gave him asylum (which is why the windows along the street are bricked up). Due to Kahlo’s popularity, admission lines have become extremely long around Day of the Dead. The way to jump the line is to buy a package ticket that includes admission and a round-trip bus to Anahuacalli. (The latter is off the beaten path, and it is very difficult to get a return taxi from Anahuacalli, so this is the best way to visit it.)

Rivera had this pyramid built in the courtyard of what is now the Kahlo Museum. The Mesoamerican sculptures visible here are permanently exhibited on this structure. The flowers, dishes, and other objects in the center were added for Day of the Dead. Anyone interested in art should spend at least half a day at the Kahlo Museum and half a day at Anahuacalli. I recommend visiting the Kahlo Museum in the morning when it is less crowded and taking the bus to Anahuacalli. After your return to the Kahlo Museum, you can spend a pleasant evening in the Coyoacán park, which is just a short walk away. It has one of the best Day of the Dead festivals (including altars) and it is attended by people who put a lot of work into their costumes. There are numerous restaurants and cafés adjacent to the park.

Museum of Popular Cultures, Altar from Santiago Zapotitlán, Tláhuac, detail, 2017, © Ruben C. Cordova.

The other “must see” stop in Coyoacán is the National Museum of Popular Cultures. Day of the Dead is the best time to visit this museum. It always has multiple altars rendered in the unique traditional styles of specific villages. This virtual smorgasbord of popular altars is a convenient way to get a sense of the diversity of Day of the Dead altars. The museum’s didactic texts (Spanish only) offer insights into local traditions.

Contemporary altars and exhibitions are also presented at this museum. It usually hosts some of the best craft artists in Mexico, who sell their works directly to the public. If all that isn’t enough, the museum usually has stalls with food vendors who sell exquisite Mexican food and drink, including tamales, mole sauces, artisanal tequilas, etc. Best of all, they offer free samples.

The Museo Casa de León Trotsky is another notable small museum that is close to both the Kahlo Museum and the Museum of Popular Cultures. After Trotsky and Kahlo had a brief affair, Trotsky sought other accommodations. Their affair had upset Trotsky’s wife Natalia. Moreover, Trotsky’s aides thought the potential revelation of the affair could serve to discredit his revolutionary activities. (Rivera, who didn’t know of the affair, didn’t mind Kahlo’s liaisons with other women, but was jealous of other men). The fortifications to the Trotsky house were added for Trotsky’security. He survived a half-hearted armed attack on May 24, 1940 perpetrated by David Alfaro Siqueiros and other Stalinists who machine-gunned the house. Trotsky was finally assassinated on August 21, 1940 by a man with an ice pick who had gained his trust. The museum usually has a modest altar dedicated to Trotsky.

Dolores Olmedo Museum, Toulous-Lautrec Painting a Can-Can Dancer at the Moulin Rouge, 2013, © Ruben C. Cordova.

The Dolores Olmedo Museum is seemingly designed to exhaust one’s supply of superlatives. It houses the world’s best collections of art by Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo (though the latter is often out on loan). The museum’s holdings of pre-Columbian art, which number more than 900 pieces, are impressive. Its collection of folk art, which includes many rare monumental works, is staggering. The setting is without equal: it is housed on lush, spacious grounds in a number of stone buildings that are said to date back to the 16th and 17th centuries, when the walled complex was known as the Hacienda La Noria. A dazzling ostentation of peacocks — which have become increasingly tame in recent years — roams the grounds. A large pack of hairless Xoloiztcuintle dogs (which are fenced off from the public) provide a sample of indigenous exoticism. Since it opened in 1994, the Olmedo Museum has consistently featured the best Day of the Dead altars in Mexico City. Perhaps they are better described as thematic installations, since they generally take up an entire building. Olmedo, who died in 2002, frequently had her portait painted by famous artists. This tradition has been continued in death: in the photograph above, she is the skeletal Can-Can dancer that Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec is painting.

The 2017 altar replicated the cinematic experience, beginning with an ersatz marquee, enormous banners, and a red carpet (seen above).

Dolores Olmedo Museum, Altar dedicated to Film, Usher and Popcorn Vendor, details, 2017, © Ruben C. Cordova.

The fiction was maintained in the interior: one entered through a split curtain, where a buxom, though (literally) skeletal pillbox-hatted usher wielded a flashlight and a box full of sugar skulls and candy. She was framed by posters of classic Mexican films, including several horror flicks. A booth with a popcorn vendor preceded the main attractions.

This was a stupendous altar, perhaps my favorite ever. The above photograph shows just a small portion of the first room, with a scene from The Vampire (1957). The conceit is that we are on the sets of various films, privy to the shooting, directing, and editing of them. I especially like the expressive wall painting. It’s the first time that I have seen blood-red lighting (an effect I’d like to replicate some day). This altar had too many admirable scenes to mention. Visitors were struck with sheer wonder before an animatronic papier-mâché rendering of Santo Vs. the Mummies of Guanajuato (1960). Unfortunately, still photography does not convey the hilarity of the herky-jerky effects of the mummy flying through the air — which mimic the primitive special effects of the low-budget film. In the scene from The Ship of Monsters (1960), the alien spacecraft is lifted off of the ground by a skeleton with a giant vintage fishing rod. The 2017 offering also featured a more traditional, fake-flower and (real) food altar dedicated to Kahlo and Rivera.

When the Olmedo Museum opened, I realized that many of the prime examples of folk art that I had seen at Anahuacalli (and to a lesser extent at the Kahlo Museum) came from the Olmedo collection. From year to year, one can see recycled bits from previous altars at these three museums. Once you visit the Olmedo Museum, you might never want to leave. It is not likely they will let you live there, so I recommend a short taxi trip to Xochimilco, where you can take a ride on a brightly colored, flat-bottomed boat through the chinampas. Often translated as floating gardens, the Aztecs grew their food on these small strips of land that were artificially built-up on the lakebed. Daytime rides are always available, either by renting an entire boat or purchasing a seat on a group boat. During Day of the Dead, night tours of the “La Llorona in Xochimilco” light show / experience are available, leaving from the Embarcadero Cuemanco Xochimilco. Tickets should be purchased in advance (they are available at Ticketmaster).

Every year, one of the most spectacular altars in Mexico City is unveiled at the Cloister of Sor Juana, fabricated on the stage of the University auditorium on the grounds of the former convent of San Jerónimo. The cloister is named after Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (c. 1650-1695), a Hieronymite nun who lived there for 27 years. She was a Baroque-era Renaissance woman, a philosopher, poet, composer, and writer dubbed “The Tenth Muse.” For more than 30 years, the annual altar has usually been dedicated to Sor Juana. (One exception was in 2013, when the altar was made in tribute to the Mexican printmaker José Guadalupe Posada on the 100th anniversary of his death.)

Cloister of Sor Juana, Altar dedicated to Sor Juana, detail, lower portion of center, 2010, © Ruben C. Cordova.

This altar treats Sor Juana’s conception of musical harmony, symbolized by the large conch shell that is pierced by a spiral of tiny holes. Red swirling patterns along its edges echo the structure of the shell, whose body features incised musical notes and crosses. The spiraling swirls of votive candles continue the structure of the shell across the surface of the stage. Twenty-five students at the university worked on this altar for two months. They fabricated strings of paper marigolds more than a mile in length that formed a cascading “tent” in the auditorium’s dome. The many statues of skeletal nuns are used year after year.

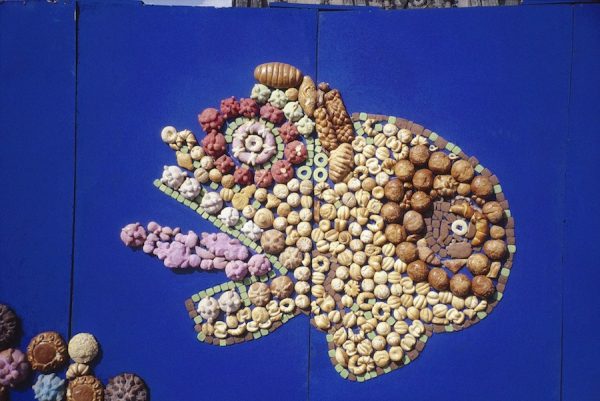

Zocalo, Mictlantecuhtli (the god of death) fashioned out of Day of the Dead bread, 2005, © Ruben C. Cordova.

Shortly before the turn of the millennium, Day of the Dead commemorations were revived in the Zocalo, the enormous square in the center of the city. Sometimes the Zocalo was lined with fences that were adorned with many of the breads baked for Day of the Dead. In the example above, the breads are fashioned into a mosaic image of the Mesoamerican god of death: a white skull with a ringed eye socket and a protruding hot pink tongue. Another bread mosaic the same year depicted Quetzalcoatl flying above the cathedral (the real cathedral was visible behind it).

By the early 2000s, the altars had become quite spectacular. Individual city districts constructed altars, often with great effort and imagination. Sometimes entire cemeteries were recreated, with tons of soil and flowers, which were transported in enormous trucks.

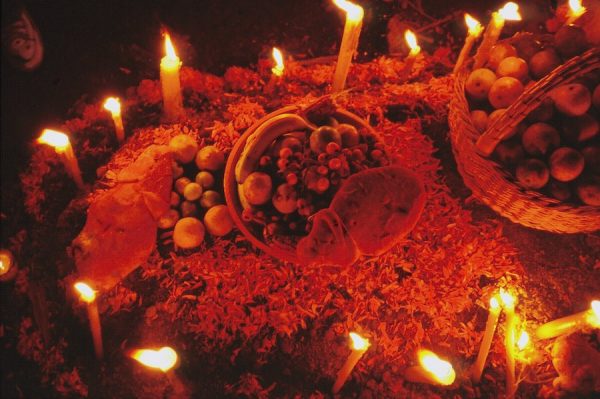

In 2003, a Oaxacan-style cemetery was the centerpiece of the Zocalo celebration. Candles were continuously extinguished by the wind, so children were enlisted to relight them. It was hilarious to see little Chuckys, Freddy Kreugers, witches, devils, and vampires tending to the flames, as in the photograph above.

This is a detail of the Oaxaca style altar, faithful down to the bread.

I’ve seen a lot of altars in my day, but only one singing altar (above), presented by the delegation from Tláhuac.

2010 was the 200th anniversary of Mexican Independence and the 100th anniversary of the Mexican Revolution. 2010 was the ultimate Mexican fiesta — and I mean all year long, not just Day of the Dead. The altars were more spectacular than usual, but nothing topped the 60 feet tall Tree of Life / Death in the Zocalo.

The light show was amazing, and, at the climactic moment, the statue spewed paper butterflies, which symbolized the souls of slain Aztec warriors.

Even its dismantling was wondrous. As the tree was ripped apart limb-by-limb, the laser show in the background made it seem like the climax of a cosmic battle.

These Day of the Dead festivities were among the activities aimed at revivifying the city center, which had not fully recovered from the devastating 1985 earthquake. Increasingly large crowds and the recent institution of the James Bond-inspired parade (which uses the Zocalo as a staging area) appear to have ended the vibrant, large-scale altar tradition of the last two decades. One might still, however, see “unauthorized” altars made by indigenous dancers between the Cathedral and the Templo Mayor on November 1 and 2. The photo above includes a girl dressed like a vampire. Quite serendipitously, the dried cotton candy around her mouth resembles blood.

The most “traditional” Day of the Dead experience is the nocturnal cemetery vigil. San Andrés Mixquic is the most beautiful cemetery in the area, and it also has Aztec era ruins. One of the most renowned colonial-era cemeteries in Mexico, it is in the borough of Tláhuac, about two hours from the center of Mexico City, whether by public transit or car.

Mexico City is place of wonder. You never know what you will find around the next corner. Sometimes, as in this case, my favorite picture on a given trip is the very last one I take. Walk a few extra steps before you rush to the airport — chances are your plane will be late in any case. Here paint divides a woman’s face into flesh and bone. This division reflects the Mesoamerican concept of dualism: the belief that life and death are deeply interdependent and interrelated. Her white gown (probably an old quinceañera dress) seems to imply that she is the bride of death.

****

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian, curator, and photographer. He served as a consultant to the Travel Channel for its Day of the Dead program in Mexico in 2006. His revisionist exhibition, “The Day of the Dead in Art,” is at Centro de Artes (the former Museo Alameda) in San Antonio through January19. It features more than 100 works by more than 50 artists. As a photographer, Cordova has exhibited nationally and internationally. His most recent solo exhibition was “Besos de la Muerte” (Kisses of Death) at Centro de Artes in 2014-15.