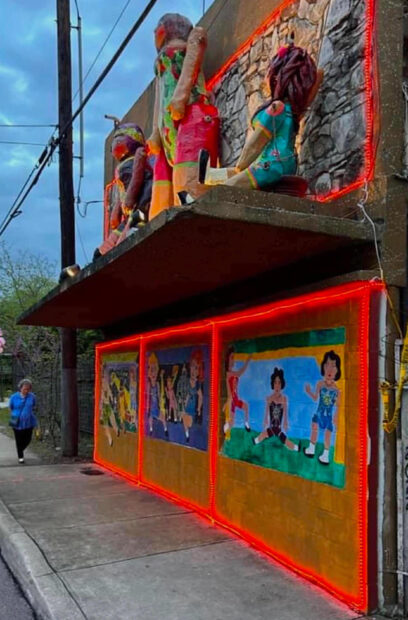

Exterior of Elizabeth Rodriguez’s home facing Guadalupe Street, with red lights, faux storefront windows, and giant Lupita dolls. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Artist Elizabeth Rodriguez lives in a strange old building on Guadalupe Street built in 1957 to house Arms Plumbing. According to local lore, confirmed by city records after the event was planned, the building served as a brothel in the 1970s and 80s, when prostitution flourished on this street in the Westside of San Antonio. This tradition was addressed in a multi-media installation/event called Muñecas en La Calle Guadalupe on the evening of March 16, when the building was illuminated with red lights to emphasize its former function.

Exterior of Elizabeth Rodriguez’s home facing Guadalupe Street, with red lights, faux storefront windows, and giant Lupita dolls. Photo: E. A. Davis.

In the post-World War II period, prostitution became deeply entrenched on Guadalupe Street, which had a high concentration of bars. When Rodriguez was in middle school in the late 1970s, students would issue this taunt: “Hey, I saw your mother on Guadalupe street,” implying that the mother in question was there turning tricks. Historically, San Antonio’s red-light districts (a.k.a “Sporting Districts”), including Guadalupe Street, never actually utilized red lights. So, in this work, Rodriguez gave material form to a trope or metaphor. Her prolonged stay in Amsterdam in 1999 had given Rodriguez familiarity with the usage of red lights to signify zones set aside for sex work.

Exterior of Elizabeth Rodriguez’s home facing Guadalupe Street, with red lights, faux storefront windows, and giant Lupita dolls. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

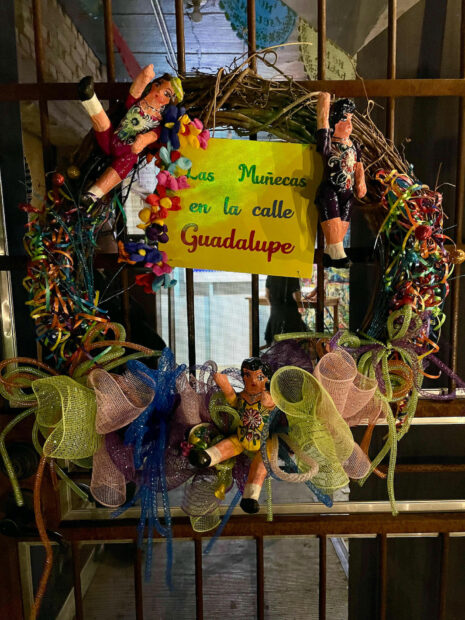

Traditional Mexican papier-mâché muñecas (dolls), known as Lupitas, formed the common thread of the installation. According to some local and Mexican traditions, these folkloric objects, when placed in windows in “red-light” districts, served to advertise the profession of prostitution. In this context, they are referred to as “puta” (whore) dolls.

Rodriguez notes, however, that there is no compelling proof that these dolls ever advertised prostitution on Guadalupe Street. Another tradition holds that a woman might buy a Lupita doll, inscribed with the name of her husband’s mistress, in order to inform him that she knew about his affair. Some artists in the exhibition addressed the theme of prostitution in connection with these dolls. Other artists, who grew up playing with these dolls, did not want to associate them with that particular profession.

Elizabeth Rodriguez studying the leg of a giant Lupita doll in progress. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Rodriguez and her assistants (which included friends, family, and students) crafted several monumental muñecas over the course of three months. Rodriguez had spent the better part of two years gathering the necessary materials (newspapers, cardboard, chicken wire, plastic bags and other lightweight materials for packing, etc.).

Andy Villareal (center), Elizabeth Rodriguez’s husband, is securing the central muñeca. He also painted the faux windows to create a virtual storefront. The building never had a real opening onto Guadalupe Street, because it served as a garage. The building was accessed from the West, facing Apache Creek. Photo: Barbara Felix.

Several muñecas were placed on the exterior of Rodriguez’s home, in surrealistically inflated homage to their reputed former role on Guadalupe Street.

The largest of these dolls would have been twenty-five feet high had it been able to stand. Rodriguez modeled her dolls on friends, as in the examples pictured above.

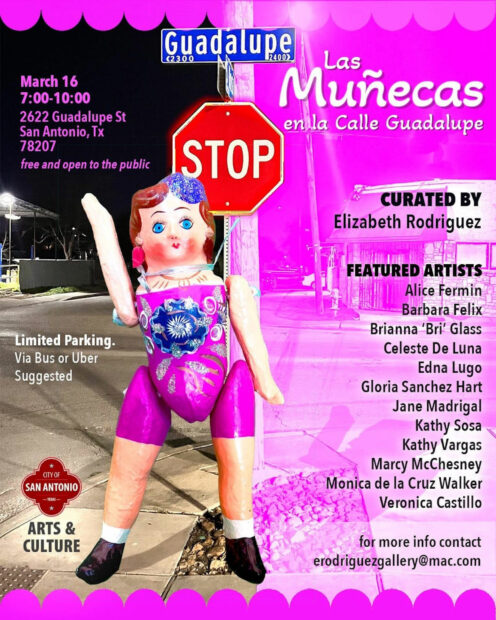

Invitation (Marta Sanchez also joined the exhibition after the invitation was printed.) Photo courtesy of the artist.

The Lupita doll served as a common iconography theme utilized by the thirteen women artists that Rodriguez invited to participate in the exhibition, whose work addressed such issues as the (contested) purpose of the traditional dolls, the history of Guadalupe Street as a red-light district, and the general folklore and symbolism of the neighborhood.

Gloria Sánchez Hart in period dress with two of her Lupita dolls. Her installation is in the background. Photo: Sabra Booth.

Due to the ongoing gentrification of the neighborhood, Rodriguez refers to the exhibition as “an exercise in nostalgia, and a way to say goodbye to the neighborhood,” which is rapidly losing its traditional character. Several artists dressed in period clothing in order to evoke the neighborhood’s earlier days.

The festivities began with Gloria Camarillo Sánchez and the AH Manam Spiritual Circle performing an opening ceremony and indigenous blessing.

They acknowledged the Coahuiltecan people’s claim to the land and they performed the Sacred Four Directions prayer.

The blessing was followed (on the other side of the building) by a fictive radio program reading. It was written by Iñez Saenz, who called it “Reina Radio FM003 – Muñecas de Cartón.”

Performance of “Reina Radio FM003 – Muñecas de Cartón,” with Guadalupe Marmolejo, Gladys Cosio-Burger, and Inez Saenz. Photo: Barbara Felix.

Addressing the pre-WWII history of the Lupita dolls, it was performed by Saenz, Gladys Cosio-Burger, and Guadalupe Marmolejo. According to this program, the doll originated as a toy, was transformed into an advertisement for prostitution, and later turned into an accusatory object bought by women who had been cheated on by their spouses.

The exhibition was preceded by many conversations, such as the one above between Veronica Castillo Salas and Elizabeth Rodriguez. Castillo Salas, who is from Pubela, Mexico, maintains that the dolls were never intended as children’s toys. Castillo Salas, who comes from a long line of Mexican artisans, spoke to families in Mexico who created these dolls over generations that confirmed this belief.

In the above painting, Castillo Salas depicts the Lupita dolls as knowing adults, within the context of the Tree of Life.

Edna Lugo and Gloria Sánchez-Hart, on the other hand, according to Rodriguez, view the dolls as toys, not as markers or signs of prostitution or infidelity.

Sánchez-Hart’s installation treats the dolls as toys that she ignored for decades. The papel picado that hangs from the ceiling makes accusatory remarks, as if spoken by the dolls to the artist (translated here from Spanish to English): “you don’t look at me, you don’t listen to me, you don’t talk to me, you don’t love me.”

Celeste DeLuna with her “Voices and Seats” installation, framed color reduction print in center (16 x 20 inches), surrounded by fourteen screenprinted panels (12 x 12 inches) on paper in the European toile style. Photo courtesy of the artist.

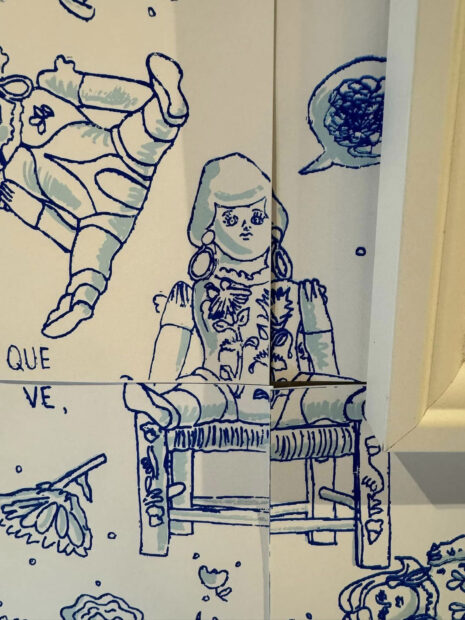

The central image in the above work derives from a photograph Celeste DeLuna took of a group of Lupita dolls at a Mexican restaurant in Houston. The dolls “struck me as both sexualized and infantilized, much like real life women are treated in regard to their bodies,” she recalls. “As a girl who always loved dolls and stuffed animals, I felt bad for them,” DeLuna added. She describes them as “struck dumb, posed with their legs open… placed on wooden Mexican toy chairs and displayed on a wall at a restaurant.” Importantly, DeLuna points out, “the Lupitas did not have a seat at a table, neither voice nor choice.”

In DeLuna’s view, the dolls are obviously sexualized. She recalls conversations Rodriguez had with women in Mexico, who denied the sexual nature of the Lupita dolls. DeLuna characterized this attitude with the phrase: “lo que se ve, no se habla” (what is seen is not spoken), which is why she uses it as an inscription in this installation.

Since the dolls are working-class folk objects, DeLuna wanted to situate them “in a ‘fancy French doll’ context.” By creating a toile-style wallpaper from the patterns of the dolls in her original print, DeLuna sought to have the dolls “subvert” what she calls “a rarefied atmosphere.” The dolls symbolize working class women, and this is how she pictures “working class women walking in other worlds.”

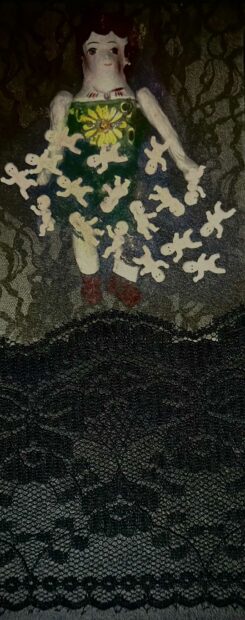

When Rodriguez invited Kathy Vargas to participate in the exhibition, she brought her a small doll to be photographed. Vargas contributed four hand-colored photographs to the exhibition.

She told me that the dolls in these photographs “are my commentary on how some politicians see women today: sweet, frilly, silent, acquiescent baby factories.”

The photograph illustrated above represents the doll as a “baby factory,” with seventeen offspring. The green color of her outfit and the flower are also symbolic of fertility. In another picture (not illustrated here), the doll is virtually buried under flowers.

In the above photograph, the Lupita doll is incorporated into a frilly doily to such a degree that her corporeal identity is compromised. Through this dematerializing dissolution, the doll takes on the qualities of the doily, implying states of frilliness and passivity.

In Kathy Sosa’s semi-abstract Tree of Life altarpiece, diminutive Lupita dolls have been painted a single, solid color, which drains their vivacity. These dolls represent the many women who lost their lives due to domestic violence.

Barbara Felix utilized dolls to create puppets, which she cut up and carved into puppets that she used for an animation that was projected on the outside of the house.

Felix’s animation was projected on the east exterior wall of the house.

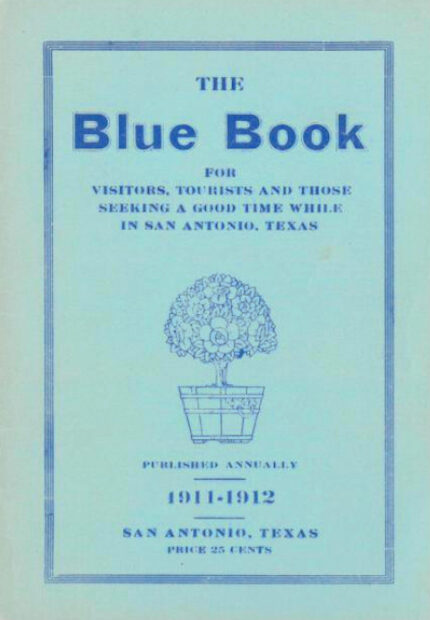

William Keilman, “San Antonio Blue Book,” 1911-12. Photo: Journal of the Life and Culture of San Antonio.

In 1911, William “Billie” Keilman, a former San Antonio policeman who was then a brothel owner, published the San Antonio Blue Book, which he sold for 25 cents. It listed “the names, locations and phone numbers of prostitutes in San Antonio’s red-light district, and it ran advertisements for saloons, restaurants and brothels” (Jennifer Cain, “Bawdy Houses ‘For Those Seeking a Good Time while in San Antonio, Texas’ – The Restrictions and Permissions of Bawdy Houses from 1889-1941,” Journal of the Life and Culture of San Antonio, University of the Incarnate Word).

According to Cain, the “Sporting District” prostitutes were given one of three designations: “A”, “B” or “C.” Whereas most “A” class prostitutes were Anglos in higher-priced brothels, the “C” class prostitutes were mostly Mexican or Black women who worked in establishments that are referred to in the Blue Book as “cribs.” Though white men could patronize all races of prostitutes, Black men were forbidden from consorting with Anglo prostitutes.

Keilman gave the impression that prostitutes were restricted to the “Sporting District” (today’s UTSA downtown campus, near Market Square), which confused early researchers on this topic, who could find no ordinances that placed geographical restrictions on prostitution. It appears that Keilman merely wanted to funnel visitors in the direction of his brothel, which he described in this manner: “In this district you will find the Beauty Saloon conducted by Billie Keilman, a safe and sane thirst parlor” (quoted in Bri Kirkham, “No boundaries? How San Antonio’s red-light district grew,” Texas Public Radio, April 1, 2022).

The U.S. military (which objected to its soldiers contracting venereal diseases) tried to shut down San Antonio’s primary red-light district during World War I. These efforts continued for decades. They were no doubt defeated by the sizable bribes that the operators of these establishments could pay to politicians and the police. Finally, the bawdy houses in the Market Square area were shuttered during World War II. This provided the opportunity for Guadalupe Street to become a prostitution hot spot in subsequent decades.

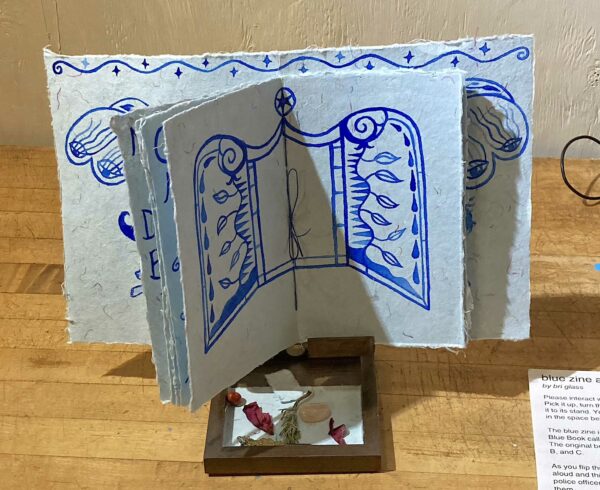

Bri Glass’ contribution to the exhibition is Blue Zine, which incorporates names and imagery from Keilman’s Blue Book, which Glass scanned at the Texana/Genealogy department of San Antonio’s Central Library.

The Blue Zine is an interactive zine on handmade paper with several illustrations of angels and altarpieces. It serves as “a paper altar to the women in the Blue Book,” some of whom have their names inscribed in it.

This cake, crowned by a large pair of red lips, was a gift to Rodriguez from Raquel Centeno, one of her students.

Night at last drew back its black curtain, and everything vanished, save for the red lights, which, for one evening, illuminated a dark corner of San Antonio’s Westside past.

Muñecas en La Calle Guadalupe, curated by Elizabeth Rodriguez, was on view at 2622 Guadalupe St. on March 16.

7 comments

I hope that my installation in “Las Muñecas de la Calle Guadalupe” has resonated with Glasstire readers and contributed significantly to the artistic conversation in our state. Your support and recognition not only validate my artistic practice but also inspire me to continue exploring and deepening my work.

I sincerely appreciate the time and thought you have dedicated not only to my work but to the entire Texas art community. I look forward to continuing to contribute to our vibrant artistic landscape and to the future discussions that you will undoubtedly foster through your critique.

Great article! Thanks for such inclusive perspectives!

Thanks for the comment, Gloria. Those who experienced the show really enjoyed it, and those who missed it wished they had not. My review of this very innovative exhibition has received a very positive response on my social media.

You are welcome, Eugene. And thank you for documenting this exhibition. I was lucky to be able to draw on many photographers, as well as the research Elizabeth and the other artists conducted on the subject of the Lupita dolls.

NICE!!! Great article! I’ve been in San Antonio since the age of four. Shameful that I’m just now learning so much about my city and how in art I’m surrounded by a unique, richly talented and diverse populated city! I’m pleased and proud how magnificently art has been displayed everywhere throughout the city. I’ve been inspired to dabble in .

The Muñecas de la Calle Guadalupe was such a unique and fantastic experience!

Gloria Hart, thank you for opening up your home for this stellar evening!!

What An Amazing Review Ruben On A Super Event. Elizabeths Exhibition And Event Was Very Well Described By Your Fantastic Review. I Believe It Was The Art Event Of The Year. My Opinion. Many People Involved Were Responsible For The Success Of The Evening. Thank You Elizabeth For Sharing Your Vision With All Of San Antonio And Beyond. I Am So Proud Of You Elizabeth.

Thanks, Andy. I’m glad you liked the review. Elizabeth found a really interesting and unique way of creating an exhibition/installation.