A few days ago, I spent a quiet afternoon in the Kimbell Art Museum’s exhibition, Bonnard’s Worlds. I have long been a fan of Pierre Bonnard’s pastel, almost neon interiors, and his deft manipulation of space and emotion through color. While I anticipated this would be a visually stunning exhibition (and it is), I underestimated the way these works — and the way they were organized — could make me consider and reconsider the complexities of intimacy. As I wandered through the luminous paintings, I pondered their intersecting manipulations of color, space, closeness, and the body, resplendent in their pigments, thunderous in their familiarity, aching in their vulnerability.

The exhibition opens with a sweeping view of the Kimbell’s 2018 acquisition, Landscape at Le Cannet. The green and orange figures and vegetation are glowing embers against the unearthly lavender light cast by the Renzo Piano Pavillion’s concrete walls. A body, perhaps Bonnard’s, dissolves into the fields on the right of the canvas, the first of many ghosts to haunt the exhibition. Sweeping views, city and pastoral, surrounding Landscape at Le Cannet, give me the uncanny sense of standing atop a tall hill or building, where neighboring bunny rabbits and anonymous allegorical figures quickly make way for distant trees, carriages, buildings, and abstraction. The sight lines between the baffle walls further orient me to the exhibition’s overall layout: a somewhat detached start is sure to give way to increasingly personal views beyond.

I next move into a narrow gallery, filled with warm golden greens and figures frozen in lively awkward movement: aiming a croquet bat, dancing a jig, playing with a puppy, picking flowers in the garden, catching rays of sun, lounging under tables, cradling infants. I trace Bonnard’s signature orange as it emanates from each painting, connecting their sometimes disparate stylistic choices in a subtle scavenger hunt I continued throughout the exhibition. We as an audience are in a park or garden rather than overlooking a pastoral vista. I get the sense I am visiting a friend from a distance, making my way toward them.

The next narrow space undulates through the color palette of the works, all at once warm and dense, chalky and muted, cool and luminous, clear and bright, glowing tutti frutti. Things begin to feel more experimental. Here, I join a family luncheon or drop by for a chat. We sit and read quietly with unfinished cups of tea, bottles of champagne, whispered conversations with children, plates of fruit, jugs of water, stolen snacks, and fresh-picked fruits. Frenetic strokes of paint and vibrant patches of abstraction lure us into the haze of memory or reverie, past moments collaged together in the mind’s eye. Our intimacy with the work grows.

The following gallery is a bridge between outside and inside: living, breathing interiors with windows to the world beyond. Figures, typically Bonnard’s wife and muse, Marthe, stare into cups of tea, tend to a bit of sewing, or perch by a window sill. The colorful interiors glow around her lavender gray skin, as if ghostly apparitions set flowers in vases and spill coffee on the tablecloth, rather than someone of flesh and blood. In this context, I am perhaps a guest or a spouse, happening upon my partner during their morning routine. We are familiar.

After a riotous yellow transition in which we look through a window, with another ghostly face on the bottom left, we enter dining rooms, kitchens, and studies. We are then gifted with a touch of everyday domesticity, including signs that people actually live in this place, with works that show papers strewn on surfaces, a cat on the table, a child trying to hold a spoon, a woman sharing her breakfast with her dog. Paintings of a pantry are my favorite. I enjoy the figure’s anonymous labor as she stocks the cupboards. I wonder how she prefers to arrange her pantry items, and I jot down a few notes for my own kitchen. I now see myself as the the one writing at the desk or scraping the butter within a quiet still life setting. Perhaps this is my home now.

Then next come the nudes: faceless women emerging from the darkness of the low-light galleries, all flesh and mussed sheets, riotous patterned quilts and wallpaper in the gloom of twilight. Only a few moments ago we, as visitors, were sharing an intimate breakfast with Marthe and her dog, and here the intimacy has escalated to something much more private, by several magnitudes of the word. And this is where the invitation to tea has ended, and my role in the narrative shifts. Perhaps I am the lamp on the shelf, or the flower in the wallpaper, or perhaps I am Bonnard himself, bringing into dreamy, luminous reality the most exposed versions of my beloved, my space, and myself. There is a hush in this space.

While the label texts point toward an overtly “erotic” reading of these paintings — an interpretation that is certainly readily available — I use this body of work to think on the word “intimacy,” employed frequently in the discourse of this show. I am interested in the connection between “intimate” and “vulnerable.” I ask myself, where do I feel most vulnerable? Certainly bedrooms and bathrooms are at the crux of that intersection. Perhaps we often use one term as a euphemism for the other. As these figures lay among their tussled sheets or emerge from their beds to drag their clothing back on, they are at once powerful in their nudity and vulnerable in their awareness.

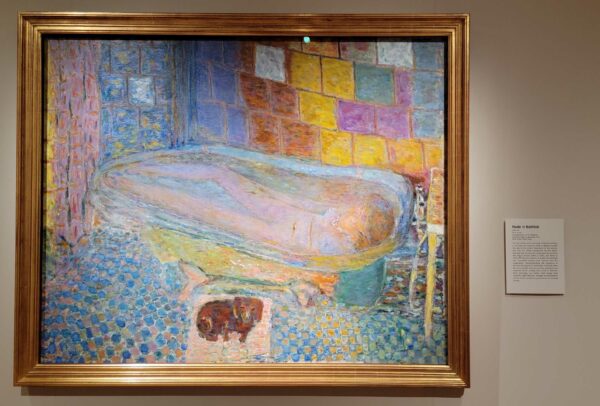

In the cozy, dimly lit gallery, spotlights illuminate painting after painting of a nude Marthe in her bedroom and bathroom, the light through the windows and water creating an incandescent glow from beneath her skin. She submerges into and emerges from tubs, disappearing and reappearing behind corners in complicated compositions that bend the rules of space. These are stolen moments. Where is Marthe going in her mind, as her body melts into the water or ties back her hair? Does she know I’m watching her?

The exhibition closes with a selection of Bonnard’s self-portraits, one of which stands in a captivating pairing with his final Nude in Bathtub, the last painting he made of Marthe, finished after her death. A lavender phantom dissolving beneath the water, floating into jewel-toned abstraction, Marthe is a mere spirit in dichotomy to her corporeal dog, curled at her side. This placement, juxtaposed with Bonnard’s harrowing expression nearby, haunts me. Bonnard has no more intimacy to illustrate, beyond what he sees of himself in the mirror. His gaunt reflection is almost too private for me.

Throughout his life, and brought into context with this exhibition, Bonnard investigates solidity and translucence, vibrancy and dinginess, public and private. As Bonnard’s characters look to the distance or stare into their cups of tea, they disappear into their thoughts, rendered in colorful abstraction. I leave Bonnard’s Worlds reflecting: When am I myself? How would anyone know? How would I show them?

Seekers of thoughtful interiors, vibrant color studies, human relationships, and a spectrum of “intimacy” should make it a point to visit Bonnard’s Worlds, on view at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth through January 28, 2024.

2 comments

Yes! Love this! (Also, “glowing tutti frutti” is an apt description.)

Wonderful account of the show, which I saw a few weeks ago. Mesmerizing. In several of the paintings, I saw Rothko “in the wings.”