Installation view of “Care/Take,” featuring works by Christine Garvey and Annie Miller. Photo: Renee Lai

I met Annie Miller and Christine Garvey when I was a graduate student at The University of Texas at Austin. I have a lot of admiration for Miller’s paintings, the weird beauty in them, and for the directness of Garvey’s work. I was really excited to see their work together in the show Care/Take at Goodluckhavefun Gallery in Austin. I was first struck by the color pink that ran through the work. I thought of the pink in the Barbie movie, which signaled the beauty of womanhood, along with the conflicting feelings of anger and frustration that can come along with the experience. I was curious to hear Garvey and Miller’s take on motherhood, storytelling, and changing identities.

Renee Lai (RL): I really enjoyed seeing your show! I loved the way your works connected both thematically and visually, through color, a buildup of layers, and the use of patterning. How do you know each other and how was the idea for this show born?

Annie Miller (AM): We met in 2017. We were both teaching at UT Austin.

Christine Garvey (CG): We shared an office, that’s how we became friends.

AM: When I met Christine I liked her right away because I thought she was cool and sassy! I remember going to her studio when it was at the Museum of Human Achievement and doing a studio visit.

CG: That’s all true, and Annie is my first painter friend.

AM: Really?

CG: Maybe you’re my second painter friend. I was always around printmakers and sculptors. I met Annie at a time where I was starting to make paintings and I had a lot of questions about them. With Annie I could think about the painterly side of my work.

AM: I don’t think I knew that… I always called the work you made paintings and drawings…

Christine Garvey, “Snakestress – clutch (blue and red),” 2023, mixed media on panel, 16 x 20 inches. Photo: Renee Lai

CG: I still don’t say I’m a painter, I say I’m an image maker. It’s funny because now the imagery in my work deals so much with classical painting. I think our friendship, Annie, and being in dialogue around painting together makes for a nice connection in our work.

The other thing that connects Annie and me is that we got pregnant around the same time.

AM: Our kids are three weeks apart. Christine told me she was pregnant and my response was “OMG I am too!” I went through IVF and my relationships when I was trying and not getting pregnant were very fraught. I lost friendships when people would tell me they were pregnant and I didn’t know how to deal with that. Christine and I got to be new moms together.

CG: I think it’s interesting because the new mom period is a massive transformation both in this new responsibility and also how you feel in the woods as a woman. You feel kind of abandoned. You’re so lost in this all-consuming experience that is very high stakes and emotional. We also live in a state where having children is scary, so I feel like relationships with other moms are a lifeline. It’s a very chaotic time, and I think it’s cool how that kind of chaos has come out in our work in different ways.

RL: How did your idea for the show come about?

CG: I wanted to do a show with Annie for a long time. Our work was definitely in conversation because it had a lot to do with the body and agency.

AM: We proposed a show before the pandemic. It didn’t come into fruition then, but we kept plotting and thinking, “how can we do something together?” Christine, you were the one who pitched this to Tim [McCool, who co-founded the gallery].

CG: Annie came up with the title for the show. It naturally was a theme that emerged in our work in different ways. What’s been so nice about the show is that seeing our work together helps clarify things that I wouldn’t have seen if it was just my work.

RL: I love the title of your show, Care/Take, which beautifully encapsulates the push and pull of motherhood. Can you talk more broadly about how motherhood has impacted your practice, especially since it is a central theme of the show?

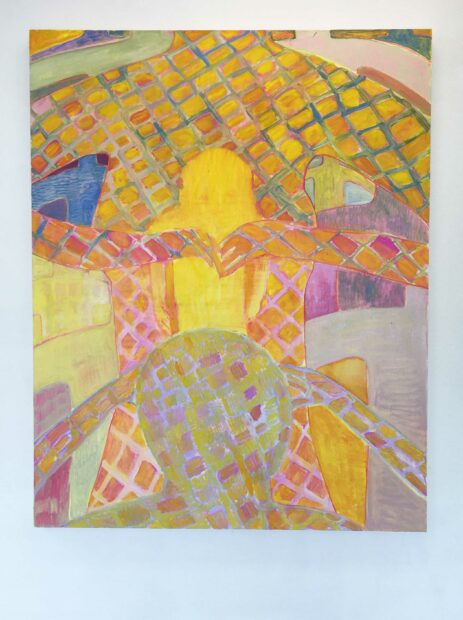

AM: I didn’t intend on making work about being a mom, but when my baby was born she would only nap as I was wearing her. I started making these really small watercolor works on paper while she was napping. I would work during moments when she was attached to me and the work organically started mirroring that. The work I made over the summer, for example, has these arms that come out from it and reach in, and I literally made different iterations of this same composition over and over. I’ve let go of that composition in the most recent work I’ve made. It feels exhausted, and letting it go has also synced up with finally weaning my child.

CG: I was going to say that I see all these viewpoints from the position of the body in your work. The body is the central point where the baby is resting and feeding and being taken from, but maybe it has been abstracted a bit. But the gestures still feel like they are there.

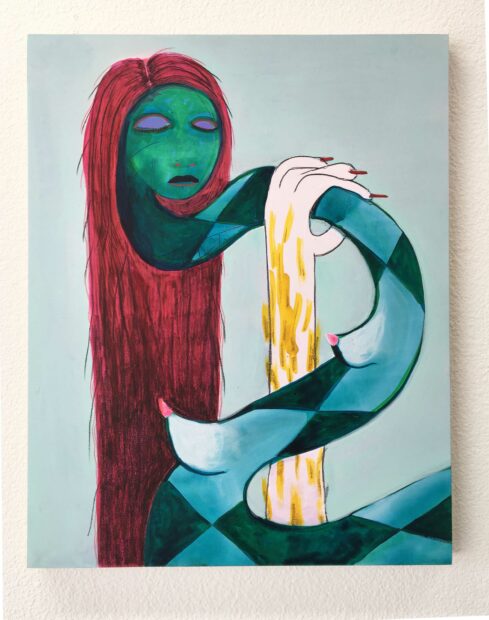

AM: I thought about this character, Ina, in the book Lapvona, a magical realism novel by Ottessa Moshfegh. Ina is this woman who goes blind, and her people cast her off. She spontaneously starts suckling herself even though she’s middle-aged and doesn’t have any kids. When she suckles herself, she regains her vision for a brief moment. She wanders back to her people and becomes a wet nurse for them, and nurses all the kids. It becomes this reciprocal thing where she talks about a little bit of herself getting into each of them. There’s something about that reciprocal nature of motherhood where a little bit of my daughter is always in me. Cells from her remain in me forever. But there is also a permeable boundary where she is her own person and she becomes more separated from me as she gets older.

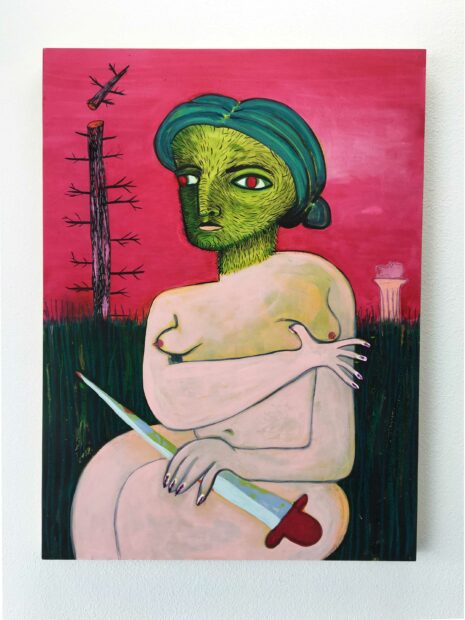

CG: I had the opposite experience of Annie, and you can see it in the work. I did not like breastfeeding. I struggled with my son’s attachment to my body and not feeling autonomous. I also had a lot of rage that came forward after Roe v. Wade was struck down. It’s hard to not be angry all the time about who has control over mothering bodies. That context is really influencing my work, which has always dealt with the body and with ruin. I started referencing Greek and Roman myths in classical paintings to understand representations of motherhood around the time I was thinking about becoming a mother. Oftentimes these stories, like the ones in the show, are stories where the woman is something to be idealized; she’s then perfected over time and sanitized by these male painters.

I’m interested in disrupting that agenda and making it more complicated. When it comes to motherhood it’s messy, it’s dark, it’s funny. A lot of my paintings are very focused on agency. My female characters become more central, or have more power, or are armed, like in the painting La Fornarina and The Tower. That painting references Raphael’s painting La Fornarina where he’s coming up with his own version of idealized beauty. I want something to be unsettling about my figures, like giving her facial hair or putting her in a posture where you don’t want to approach her. I draw from ancient stories and attempt to find the dark consequences that come when we try to control someone else’s body.

Christine Garvey, “La Fornarina and The Tower,” 2023, mixed media on panel, 30 x 40 inches. Photo: Renee Lai

RL: Christine, I think of your women as rebels, in a good way. There is a much darker energy, whereas Annie’s work feels more contemplative.

AM: I would say Christine’s figures are definitely more aggressive than mine. I don’t feel like my paintings are about anger, even though I am angry about the same things she just talked about. However, I’m not actively thinking about it when I’m making this work.

CG: I think the actions in Annie’s paintings are more about a pulling of sorts, and the actions in mine are faster and more violent. They’re more overt.

AM: In my paintings, I’ve been trying to say something, covering it up, and then saying it and covering it up again before finally finding it. My paintings have slowed down a lot. When I was in grad school I would paint all the time, whenever I wanted to. I paint differently now. I’m always trying to figure out time and how to claim a little bit of it. I paint in the evenings after my daughter goes to bed. I am interested in making problems for myself, trying to solve them, and making more problems for myself in the paintings. I don’t ever find an answer, but I find some sort of resolution.

CG: I have the opposite approach. I feel like I’ve become more overt because I don’t have enough time. I have to be direct — how can I be over-the-top in my symbols and gestures because of the feelings I’m having? We’ve created two different strategies for the same problem.

RL: I talk about paintings the same way you do Annie — they are also an endless puzzle for me and I’m never bored by them.

AM: Have you read the Amy Sillman essay “Shit Happens: Notes on Awkwardness”? She talks a lot about that. A big thing that I’ve thought about forever is that as painters, a lot of us have this oppressive history we have to grapple with. Trying to situate myself in a lineage of painters is something I’ve thought about for a long time. I think of Amy Sillman as my art mom. I’ve also been thinking about the role of abstraction and modernism and Jewish-American painters, like Frank Stella and Morris Lewis and all those guys. My identity as a mom feels like an abstraction and my identity as a Jew feels like an abstraction.

I’ve been reading this book called Abstraction and the Holocaust by Mark Godfrey and thinking about why abstraction was so prevalent in painting after WWII ended. Being an American Jew is a confusing thing right now and it’s something I’m trying to figure out in my work.

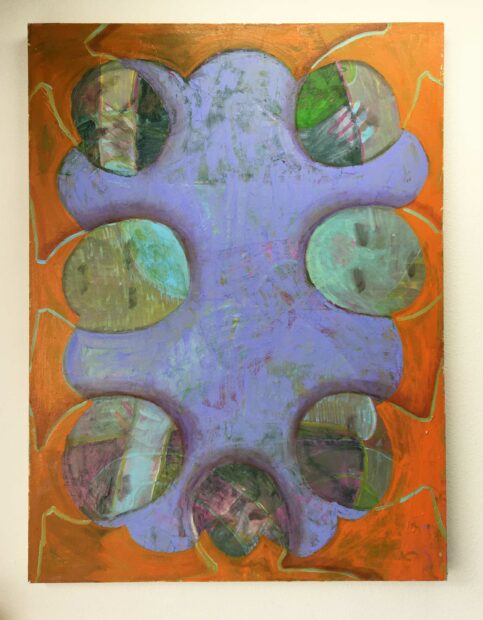

RL: You sort of answered my question already, but I’ll ask it anyways in case you have anything else to add! I love the way forms weave in and out of textures in your work. I am interested in the painting Last Name, where these pared-down faces feel like they’re in a cloud or a thought bubble. The faces read slowly to me — it took me a while to see them when I was looking at your painting as a whole. Can you talk about your process of making these images?

AM: That painting is about my last name, which is Miller. When my family immigrated through Ellis Island it was Blasenstein, and it was changed to Miller. When I was growing up no one could tell me what exactly happened — were there intermediate steps in the name change? Miller represents this process that happened to either assimilate or remove the Jewish-sounding last name. I don’t know if my great grandfather came up with the name or if the people at Ellis Island said, “I don’t know how to spell that, we’ll just call you Miller.” If I showed you what this painting looked like before, you’d think there is no way this is the same painting. And sometimes I’ll do that purposely — I’ll make a layer that is almost sacrificial that I’ll cover up to reveal something later on. A lot of times I just make bad moves, and then there’s a certain amount of having to fight with the painting.

Usually there’s radial symmetry or some sort of symmetry in my paintings, and I had this idea — what if the heads came in all directions, and then I thought “ok, I’m going to do that.” There’s a lot of improvisation, and I think about the “yes and” in my paintings: an idea comes to me and I think, “I’m going to do it,” and then do the next thing, then the next thing, and then exhaust it until I find the edge where it becomes stupid or absurd.

Care/Take is on view at Goodluckhavefun Gallery in Austin, TX through January 27, 2024.