“National parks are the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American,

absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.”

—Wallace Stegner, 1983

“Can I call you back?” asks artist Alice Leese in the middle of our interview, explaining, “A neighbor just called and said the gate was open and some cows are out.” She returns within minutes, though: turns out it was a false alarm. A fourth-generation West Texas rancher, Leese has alluded to the tension between working cattle and making art before — the intersection of flexibility and necessity that drives her day-to-day routine.

“Now, where were we?” she prompts, settling back into our video chat.

“I was just asking you about your reference to your art as regionalist and how regionalism is significant to you as an artist, and — in general — in art today . . .”

Leese pauses for a moment, considering. “All plein air painting is regionalism because you’re painting a specific place,” she begins. “When you’re painting a place, you’re conveying that specific area to your audience — by nature, it’s going to be regionalism.” Then she adds, circling back around to her works currently on display at Lubbock Christian University — paintings she completed over four separate residencies with the National Parks Arts Foundation (NPAF) — “The U.S. has over four hundred national parks and monuments. I’ll bet that most citizens have been to no more than twenty.” If that.

Leese’s role, as she sees it, is to convey an idea of a place, to show the diversity of the varied regions of the U.S., and, in this case, the three national parks and monuments that served as the locations for her residencies: Fort Union National Monument (New Mexico, 2018), Volcanos National Park (Hawaii, where she’s been in residence twice: 2019, 2022), and Dry Tortugas National Park (Florida, 2022). But the place alone is not the point. “One of my themes for presenting place is conservation: Here is what we have. What are we going to do with it?”

It’s not just the land on its own, after all; it’s people in the land. There’s a delicate balance, Leese points out, between compromise (meeting the needs of society) and stewardship (protecting land and ecosystems). Sometimes the friction between those two things is jarring, as depicted in her earlier paintings of wind turbines and electrical substations, which are tucked awkwardly into the remote sandhills between Kermit and Andrews. Other times, the strain is devastating, as in her scenes of the Frying Pan Fire, a conflagration ignited by power lines near Andrews in 2011, when over one hundred square miles burned within the span of half a week.

Leese has said, on more than one occasion, that she wants to convey to the viewer not just a scene, but, rather, what it feels like to be in a particular place. Regarding her national parks paintings, she expands, “I’m not interested in doing a historical painting of any of the places I’ve been to. I want to show what the place is like right now.” How has this delicate balance of conservation and history been managed by the national parks and monuments?

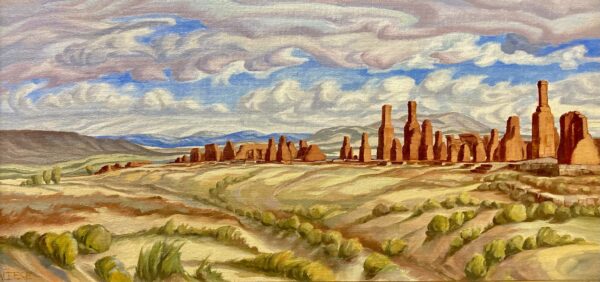

Indeed, there is mutual encroachment manifest in Leese’s residency paintings: yes, humanity’s interposition upon nature, to be sure, but also nature’s own unrelenting reinsertion of itself onto human-built environments. One sees this in the crumbling Fort Union adobe ruins in Looking North 5: “They spend six months each year building it back up, and nature spends the other six months wearing it down,” Leese says of the site.

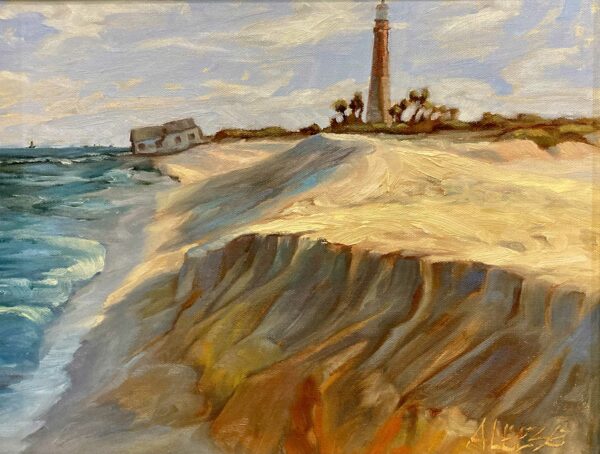

That same inexorable-obliteration-in-slow-motion is evident in Loggerhead Key, West Beach, which depicts a century-old boat house in its process of succumbing to the Atlantic. Even when a human-built environment is not in sight, Leese’s landscapes still evoke civilization at the mercy of nature, as in Kahuku 1868 Lava Flow, which references a volcanic event that destroyed 4,000 acres of Kahuku Ranch grazing land. During this flow, one family was surrounded by a sea of lava, trapped for ten days on their terrestrial liferaft.

Human interaction (in concert and in conflict) with the natural environments of the parks system doesn’t just appear as subject matter within Leese’s paintings; it is the reality of the residency experience itself. Obtaining a residency, in the first place, is a challenge — Leese applied for five years before she was accepted, and once she was, she found that her sharply honed skills in flexibility served her well. The Fort Union residency was delayed for months due to snow and rain, as well as to that seasonal propping-up of the adobe ruins. For Loggerhead Key, hurricanes and a rat infestation postponed her arrival. Here, Leese and her husband brought their month’s-worth of food with them on the ferry, then waved that transport good-bye. There was no fresh water or electricity on the island (but accommodations included a solar array and a desalination plant), and no cell service. For reasons of safety, a minimum of two people is required for Florida’s Dry Tortugas residency.

I ask Leese about this remoteness, the isolated locales of both her West Texas works and her national parks residencies. “All of the residencies have been a great fit because I don’t care if I never see another person,” she admits with a laugh. While some art residents may have a hard time being alone, or a fear of those wide, open spaces (she tells me of one artist who left her residency early because of this), Leese points out that being holed up in remote Dry Tortugas isn’t so different from life on the ranch. “We’re used to not seeing other people, to taking care of ourselves. What’s different is the landscape, the region; but I see more people on the national park residencies than at home.”

And there’s not much else to do but work when you’re marooned on a desert island: Leese came away from her month on Loggerhead Key with fifty-nine new paintings. (For anyone out there who is interested, there are two sites in Texas that offer art residencies for composers, visual artists, and writers: Guadalupe Mountains National Park and Big Bend National Park. Information on nation-wide parks residency opportunities is available on the National Parks Service website, as well.)

Alice Leese understands that she’s upholding a tradition of artists-in-national-parks that is older than the parks themselves. Beginning with painter George Catlin, who first conceived of a national parks system in the mid-19th century, to landscape artist Thomas Moran, whose works influenced the designation of Yellowstone as the first national park, in 1872, to the 2014 founding of the NPAF by Tanya Ortega, the national parks and the visual arts have been woven together as part of the warp and weft of U.S. art history. The parks’ (often) sheer vastness, their opportunities for solitude (an ever-increasing challenge), and their beguiling sense of permanence in a seemingly unpredictable world acts as both balm and buffer for those privileged to visit them. For others of us, there are, fortunately, artists like Alice Leese who record and share these places so that, for a moment, we might feel what it is like to be in these places, as they are, right now.

Alice Leese: National Parks Foundation Residency Paintings is on view at the Lubbock Christian University Art Galleries, Diana Ling Center for Academic Achievement, (5601 19th Street) through September 29, 2023. There will be a reception for the show on Thursday, September 21 from 5:30-6:30 p.m.