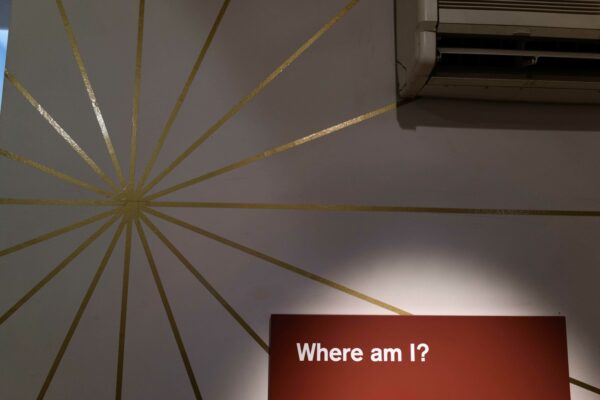

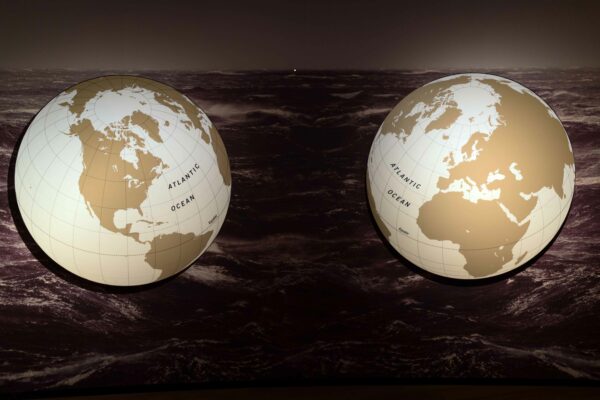

Absolutely lost in old hard drives, attempting to extract hope from my own past, I come across a cluster of nested folders with increasingly manic names. Inside a subfolder called “Yes” is “These ones,” which in turn holds “Yeah!” Inside “Yeah!” are “Actually good” and “No no.” “Actually good” and “No no,” it turns out, contain identical sets of image files. I forgot about all these pictures. They’re mine, made across two continents and dozens of institutions nearly a decade ago. I never did much with them when they were new. I didn’t have the time. Rediscovering them, one thought springs back to mind: It has long seemed obvious that they all depict the same place. The goal now, the fun part, is to figure out where that is.

This glowing 2D place, which we must pretend for the length of this essay is real, is the brand-new Oliver Museum of Museums in Photographs (OMOMIP). Standing for the first time in the grand entryway, which happens to be adjacent to the snack bar and so smells occasionally of Sysco products kept somewhat warm, I catch a glimpse of my reflection in a picture frame. My outfit is adequate. It is correct for my profession, which is tour guide. I have a blue blazer, nothing special — it’s from J. Crew’s Cyber Monday event. It fits well, the blazer, because I had it tailored. I’ve only been to the tailor once in my life, but I’m glad I went that time. If the blazer didn’t fit so well, I might not seem like I knew what I was talking about. Something about my arms appearing to be the correct length for my body portrays confidence, reliability.

Besides the blazer I’m wearing eyeglasses, a shirt, pants, and shoes. There’s no need to go very deep on any of those articles. Call them “the usual.” It’s really all about the blazer, which is pressed asymmetrically to my body from the weight of a black nylon strap that I kept slung over my shoulder. The strap is attached to a raw canvas quiver, which has so many unfinished wood dowels sticking out its open end. The tips of the dowels are color-coded, and I’ve memorized the code. It would be embarrassing to mix up the code. Here, today, right now, my first-ever tour group has assembled in front of me. I suck once on my teeth and whip out the dowel with the blue tip. A little matching blue flag unfurls and flops under the downward pressure of the air conditioning. I take a deep breath, and begin:

“Hello and welcome to the Oliver. My name is Bucky Miller, and I’ll be your guide to the museum’s wonderful collection today. You can tell that I’m your guide because of this little blue flag I’m carrying. It says ‘GUIDE’ on it in white letters, printed on both sides so you can’t get confused. I’ll flap it around in little circles for you. Guides like me, we like to carry little flags on wood dowels like this one so that our tour groups can’t get lost. At the British Museum, for example, some people might have to use the restroom during the tour. That ends up being fine, usually, mostly on account of the flags. People can track down the flags, even after they’ve lost time to the bathroom. The tour group never has to wait up. The people who go to the bathroom can just look for the guide’s flag when they’re done, after they’ve washed their hands. They can scamper back over. That’s how it works at the British Museum.

“It’s a bit different here. You aren’t too likely to get lost in this text, and if you happen to go to the bathroom while reading through this it wouldn’t be a big deal. Nobody is going to make this browser window keep scrolling without you here. Nobody. Still, it’s important that I carry this little blue flag and wave it around in tight circles. You’ll see that I wave entirely with my wrist. I keep my elbow bent in a perfect, rigid L. My wrist goes wild; it’s like a Vitamix, and keeps the flag fluttering. Nothing else moves, and you can bet no part of my arm returns down to my side until we’re done with the tour.

“This is for your benefit. Even at a text-based museum like the Oliver, the flag will help you from getting lost. You see, I’m not just the tour guide. I’m the museum’s only employee. I do it all, and I have a different little flag for each role. Say, for instance, I wanted to ask you for money (I don’t, not right now): I’d wave around my little orange flag that says ‘DEVELOPMENT’ on both sides. That way you’d know I was making a legitimate request for a donation, not doing a scam. I’d whip out the red ‘GUARD’ flag if I caught you downloading our images, printing them out, and standing too close to them. Please don’t do that. Always maintain a respectful distance from the displays. I really hope the ‘GUARD’ flag won’t be necessary. I don’t think it will. You look like a good bunch.

“We should begin the tour, but first I have a special treat for you all.”

With that, I pause dramatically and sheath my ‘GUIDE’ flag. I draw another, identically shaped flag from the quiver. This one is beige and it has ‘EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’ written in white letters on both sides:

A NOTE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF OMOMIP, BUCKY MILLER, ON THE ORIGIN OF THE MUSEUM’S NAME, THAT IS, ‘OLIVER’

“Hello. Put simply, The Oliver is named after a cat I once knew. He was a faded old tabby who had different names depending on which side of the street he was standing. On the side where my work was, he was Oliver. So it’s a tribute to him, to that cat. But there’s more. Amongst the staff here at OMOMIP (pronounce it ‘oh-mo-mip’ or ‘aum-aum-ip,’ whatever feels right), we like to keep a little joke in the air. It’s a pun, I guess. We say we’re called the Oliver because ‘all of our’ collection was taken from other museums. And while those primary institutions, as we call them, all exhibited their wares in the typical three dimensions, ‘all of our’ collection exists exclusively in photographs. Everything flattened and extracted, peppered throughout ‘all of our’ our lovely halls. It’s hard work, a museum. Long hours. It helps when the staff can bond over little jokes.”

I blink slowly. Okay. Beige flag gone, blue flag out, “let us now commence the tour. Please step right this way. There’s a lot to see. You’ll notice right away that we are not an art museum. Or maybe a better way to say that is, we have collected works from museums that would not traditionally be identified as art museums. We turn their junk into photographs. When they don’t show art, museums are a lot like photographs anyway. Do you like natural history museums? Well, photographs perform their own sort of taxidermy. I heard someone say that once.

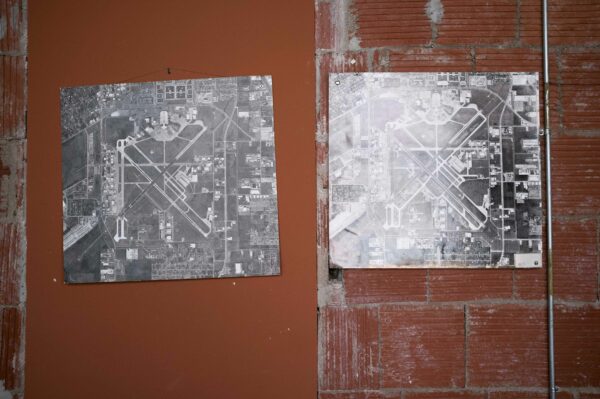

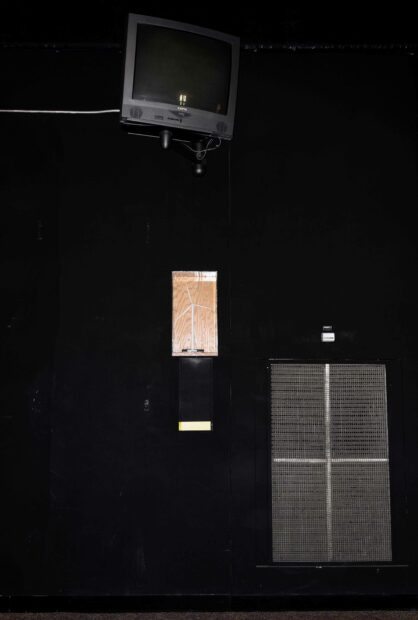

“Displays: Presentations of very select sets of visual data, removed from time but often in constant reference to some particular point in the past. Occasionally they’re a bit more speculative or generalized, but they tend to point backwards. More often than not they attest to veracity, or whatever veracity is called when it’s beholden to a specific point of view. They present facts as digestible images. Think of them as highlight reels. Think of the digestible images in terms of ‘imagination.’ Display, photograph, display, photograph, display. When one sits adjacent to another, associations can bubble up in the negative space between the two. These associations can creep into the onlooker’s looking. As more displays get stacked next to each other, sometimes even overlapping, a complex network of legible, though obtuse, messages begins to emerge. These transmissions are indefinite and highly interpretable. Display. That’s what we photograph here. Photography…” sometimes I trail off when I try to visualize and articulate exactly what photographs do. I should learn to leverage this for dramatic effect during my tours.

“We can learn a lot from what rejects language,” I blurt.

“We can learn a lot from what rejects language,” I blurt.

“A common question on these tours is about where we found all this stuff. As you can already see, the Aumaumip collection provides a diverse visual feast for our viewers. And the truth is, we’re not allowed to reveal where it all came from. The director feels,” at this I briefly unsheath my beige flag with my left hand and wave it half-mockingly while keeping the blue flag aloft in my right. I assume a sour facial expression as I say the next sentence in an affected, nasal voice, “to reveal our sources would be like a magician pointing out his trap doors.”

I house the beige flag. “So what can I do? Company policy. The ‘where’ is off limits. What I can tell you is when we amassed our collection. The Aumaumip Core, as we call it, was brought together around a decade ago, around the year 2014, by our founder, Bucky Miller. It was the feeling at the time that, since we were a museum, nothing in our collection should appear to be too new. Even though the displays we were collecting back then were adequately caked in the dust of time, our photographs, and thereby our entire collection, felt too shiny. We were using top-of-the-line, early 2010s digital cameras. Please step this way, through this door. The house lights will come on in a moment. Where was I? Oh, a museum full of all-new objects is untrustworthy, and patina is a museum’s CV. It bestows credibility upon a collection. So said our founder, upon becoming enraptured by a little museum in small-town Texas. In fact, as you will soon see, it was that one impromptu visit to the 20th Century Technology Museum that inspired him to start this very institution.

“We are now standing in Ohmomip’s screening room, the Bentley Kiwak Memorial Theater. Please take a seat, and allow me a moment to pop in this DVD.”

The projector clicks on. A recorded image of a minor, desolate highway appears in perfect one-point perspective. A man jogs onto screen from the position of the camera and nearly finds his mark in the center of the frame. Clearly he’s alone, has his camera on a tripod, pressed record himself. He stands and faces the lens. As my tour group can all see, this man is me. Except the projected version is about ten years my junior, and he is waving a little gold flag that says ‘FOUNDER.’ Previous Me stands in the middle of that country road flanked by fields, squinting. Everything is bleached out, ostentatiously sunny: that’s Texas. Previous Me looks about the same as the me who is standing in the theater running the projector, just better, and minus the glasses. But the arms on his blazer are too long. The ‘FOUNDER’ flag whips frantically in the wind. He has no microphone and has to yell to be heard by the camera. Despite this he sounds quite sure of himself:

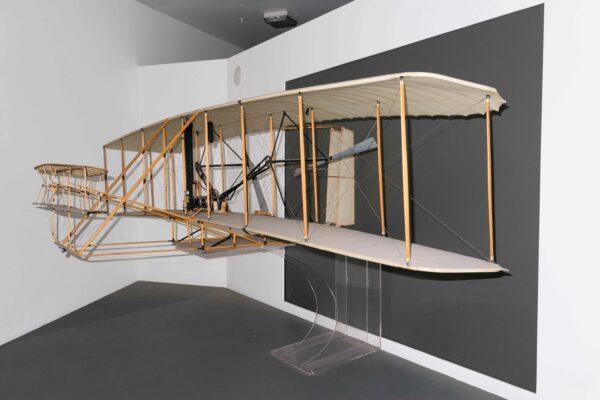

“Should visitors to the Teepee Motel in Wharton, Texas look out from their dated rooms and across the county highway that passes through this little town, they will notice a boxy, unassuming metal building. Bolted to the beige façade of that barn-like structure, in large black letters, is the word ‘MUSEUM.’ Lost and curious tourists who venture inside will realize that they have found the 20th Century Technology Museum, a wunderkammer chronology of a hundred years in engineering and commerce. Radios, early cellular phones, and boxy computers abound, but two of the main attractions — in one instance literally serving as the sign for the museum outside — are homemade airplanes. Both look kind of funky — a little beat up, with alarmingly unorthodox parts — and indeed, a quick check of the didactics shows that neither of these planes could ever fly. Presented as a ‘tribute to the ingenuity of great 20th century men,’ the planes are suspended above the viewer’s head, fixed by wires and poles into the gradual ascent they never achieved. One of two is piloted, incidentally, by a plush Snoopy.”

The screen kinda freezes at this point. Previous Me keeps talking, but his lips no longer sync up to the projection. What follows may be a voiceover that was recorded later: “The greatest thing about the 20th Century Technology Museum is that it refuses to acknowledge the present. It does exactly what it claims, and no more. The newest computer in the place is one of those boxy blue iMacs. The place has no idea what we’ve done to phones. With this confident portrayal of the near-past, the proprietors have exemplified one of the most important parts of the museum experience: Patina. The proprietors’ father, it seems, might have once been a mere hoarder. They told me he had accumulated the entire contents of the museum and left it all sitting in a storage unit. But his children saw beauty in their pop’s collecting, and so put order to a century of junk. Patina is a museum’s CV. It bestows credibility upon a collection. Think about it: Who today would want to see a museum full of stuff from 2015?”

The projector abruptly shuts off and the light comes up. The version of me who is physically present in the theater chuckles, “So that’s that. And, ironically enough. That’s just what we have here today: A museum full of stuff from 2015. Well, and thereabouts. But as you will see, these objects themselves now belong to history. Time, how weird,” a pause, “Now come along, as we have much more to explore. I’ve barely told you anything yet.”

One of my guests raises their hand, asks me how much of our collection came from the 20th Century Technology Museum.

“None,” I say.

I lead us through a doorway and back out into the light.

Next time, Part 2: Displaying Play.

1 comment

Like.