It’s not a question of “if” but “when.”

Not if your laptop, phone, or tablet will stop working, but when. When will a shiny piece of new electronics become so slow, irritating, and useless that it is functionally irrelevant? When will the thing cease to be the original thing purchased and become, instead, something in need of an upgrade? And upgrade — buy again, use again, consume again, and dispose again — consumers inevitably do.

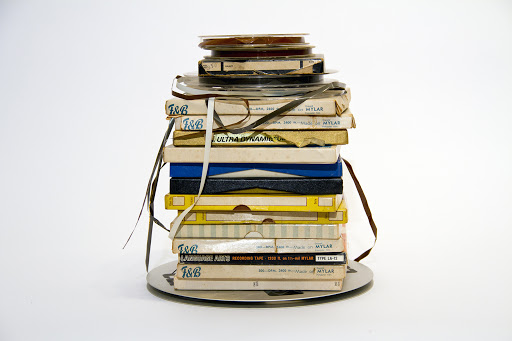

In the new book Upgrade Available, artist and professor Julia Christensen, who is based in Oberlin, Ohio, explores the relentlessness of 21st century Western “upgrade culture.” Not only does our constant upgrading fundamentally impact our perception and experience of time, she argues, it shapes how we, individually and culturally, document and share ourselves as well as our legacies.

From the international ramifications of e-waste to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s desire to “update” (upgrade?) the famous Voyager spacecrafts’ 1977 “Golden Record,” Christensen demonstrates that upgrade culture is more than just a rebuke of capitalism’s churn and the disposability we assign to electronics. Christensen’s own design concepts that build an object’s upgrade into the very material makeup of the object itself has the potential to alter how we expect objects to be created, used, and cast off.

“Electronic waste sits at the intersection of everything, really — politics, consumerism, capitalism, colonialism, globalization, the economy, the environment, and so forth,” Christensen opens with in Upgrade Available. “I’ve realized that the scale of the e-waste crisis is, in part, about the complex relationship we have with our electronics and technology in the first place.”

What, exactly, is electronic waste? Broadly, electronic waste — e-waste — refers to discarded electronic devices, whether they are destined for the dump, recycling, or the reclamation of valuable parts. Working with discarded electronics is dangerous — the devices contain lead, beryllium, and other toxic compounds — and poses significant health risks to workers who pick through and process the bits and pieces. (According to a 2019 report for the World Economic Forum, e-waste is the fastest growing waste problem in the world.) When we “recycle” our devices, they are not simply remade into new things; our attachment to the device may be ephemeral, but the physical carcasses of discarded electronics will remain in humanity’s material record for a long, long time.

This is particularly true as more recent electronics have actively discouraged our ability to repair or reuse a piece of equipment once it has passed its non-optimal phase. And that’s not necessarily driven by consumers’ demand for the newest or latest gadget; the push also comes from the manufacturers. So you may be able to get your iPhone 4 to turn on and “work,” but at some point it won’t function the way it “ought” to.

For starters, lithium batteries degrade over time, and your gadget won’t keep a charge. (And manufacturers make it difficult to replace a lithium battery.) Secondly, and more systemically, all of our technology is connected — the iPhone 4 might turn on, but the rest of its technology ecosystem has moved on and evolved. Some tools are not connected to the rest of the world, but cell phones are. This is why a person can use a hundred-year-old hammer to hang a picture, but a cell phone from 2012 is functionally extinct. “You cannot even open them now — or find the spare parts,” offers Ravi Agarwal, an artist and director of Toxic Links in New Delhi, in an interview with Christensen in Upgrade Available’s introduction. “A phone is just a locked black box. It’s about designed obsolescence.”

Dealing with e-waste — physically processing it — is an example of how “out of sight, out of mind” haunts 21st century Western consumers. When we “recycle” our electronics, those electronics are shipped far away, often to laborers in developing countries. “How do we have productive agency in all this?” Ravi Agarwal asks readers to consider. “We cannot just become the ‘complaining agency.’ [A reference to Toxic Links.] It is so difficult to pin down the right questions when we are so overwhelmed that there seem to be no answers. But we need to find agency.”

It feels incredibly fitting and meta that Wikipedia’s “electronic waste” entry has a snippy editorial box at the top of the page, dated February 2020, that chastises the tone and style of the entry as not “meeting encyclopedic expectations.” One could argue, as Christensen does, that it’s impossible for electronic waste to be described through any sort of faux neutrality. Electronic waste is fundamentally social, cultural, political, physical, and personal.

It’s hard to imagine something as banal as e-waste (and, by extension, Upgrade Available) sitting so materially and metaphorically at the intersection of the Anthropocene, human agency, and personal archives. Although planned outmodedness isn’t unique to electronics, the idea that the technology that holds a person’s personal archive — a cell phone holds photos, driving directions, and a user’s catalog of apps — is non-permanent is a very different way of thinking about our relationship with technology over millennia of human history. Our devices might be personal archives, but we upgrade, the logic goes, because we are part of a social ecosystem of interconnected parts.

Upgrade Available reads like a carefully curated exhibition, drawing from interviews, art, archives, and cultural theory. Broken into four sections, Christensen pushes the questions of inevitability and ephemerality of material technology in nuanced, careful, and curious ways. Christensen’s sculptural installation Burnout, for example, is a series of video projectors lit by old “non-working” iPhones — it illuminates, as it were, the “afterlives” of discarded cell phones. The variety of media she offers audiences to unpack this deep, complex theme guarantees a new way of thinking about the upgrade phenomenon.

Capitalism, consumerism, and humanity’s obsession with “stuff” are popular themes in current nonfiction; Christensen’s approach in Upgrade Available feels genuinely innovative, thoughtful, and interdisciplinary. She asks readers to believe that our relationship with technology, and its rapid evolution, isn’t inevitable. And she entreats readers to imagine a way for technology, and its associated politics and economics, to be better.

‘Upgrade Available’ is available for purchase here.