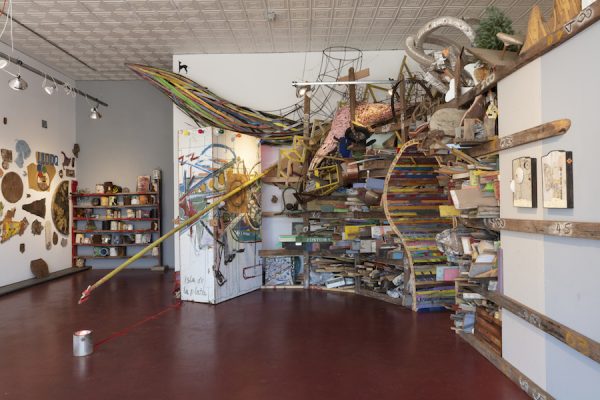

Installation view of Patrick Renner’s “Bounty” at Redbud Gallery, Houston. (All images: Emily Peacock)

I am reading The Lives of the Artists, a collection of Calvin Tomkins’ profiles that he wrote for The New Yorker. The first he wrote was in 1962 — a lengthy profile of Jean Tinguely, centered around Tinguely’s creation of Homage to New York, which is a self-destructing mechanical sculpture made mainly from junk and second-hand machines. The machine destroyed itself in the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art in 1960.

In the profile, Tinguely is taken to a vast junkyard in New Jersey to scout for materials. According to his host, Billy Klüver, “. . . when he came out and saw the dump he fell in love with the place. He wanted to live there. He had the idea that if he could just find the right girl, they could live right in the dump, like the bums there did, in a little shack, and he could spend his time building large, involved constructions, and that eventually the bums would become his friends and help him, although the word ‘art’ was never to be mentioned and his constructions would never be anything but part of the dump.”

I thought about this when I read Renner’s artist statement for his installation and show, Bounty, which is currently on view at Redbud Gallery in Houston. Renner wrote: “Initially, out of necessity as a high school student with extremely modest means, I took notice of the abundance of (free!) architectural refuse that showed up at regular intervals in random places on Houston roadsides. My first foray into the trash pile treasure pile was epiphanal, and I was hooked. Even now, after more than 20 years of sifting through mountains of detritus, I still find my head turning unconsciously as I drive past a promising pile of pre-art.” Renner, like Tinguely, not only makes use of these cast-off materials; he loves them.

Bounty is both a retrospective of Renner’s best-known work, and a statement about his love of junk. His two best-known works are probably the long-lived (but not permanent) public sculptures Funnel Tunnel and Trumpet Flower. Funnel Tunnel was a snaky trumpet-shaped sculpture situated on Montrose Boulevard in Houston, installed in 2013, where it remained for 18 months. Then it was moved to New Orleans, where it still stands (and where, according to Renner, “it needs some TLC after ~5 years… ”). When it was first proposed, I thought the drawings made it look like a vuvuzela, the South African noise-makers that were used to deafening effect during the 2010 World Cup. Trumpet Flower, from 2016, was built around a similar principle, but placed on its end. It tapered from a wide bottom to a narrow top, and anchored to the top of a six-story parking garage. It was located in downtown Houston for two and a half years, and it made a lovely shady spot, where the wide part of the trumpet acted an enormous upside-down parasol for strollers.

In Bounty, Renner references both of these earlier pieces. The show at Redbud includes a remnant of Funnel Tunnel and a scale model of Trumpet Flower called downtowncrown. The Funnel Tunnel remnant is part of the “tail” of the original sculpture; renner refabricated the tail for the New Orleans version. downtowncrown was created after the original Trumpet Flower installation. By incorporating these and other earlier works, Bounty is Renner’s own massive version of Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise, from 1935, which was a portable retrospective of Duchamp’s works up to that time. But Bounty is anything but portable.

Boîte-en-valise and Bounty are species of artistic autobiography. Unlike the literary form, Bounty is not a narrative, except by implication. Bounty is also a simulation of Renner’s work environment (worktables and tools, stacks of lumber and various pieces of detritus) — in recreating a symbolic version of his workshop, he echoes another earlier masterwork: Gustave Courbet’s The Painter’s Studio: A real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life (1855). That painting depicts Courbet’s studio and the artistic (and moral) decisions he had to make: turning away from romanticism (symbolized by the nude woman behind him, and the dagger and guitar on the floor to his left) and toward realism (as symbolized by the ordinary people standing on the left and the landscape he’s painting).

Bounty does something similar. downtowncrown was a piece made after the construction and installation of Trumpet Flower. It was a meditation on the dichotomy between the meanderings of downtown’s Houston’s huge homeless population and the determined passage of downtown workers — a difference between people with someplace to go and people with none. But all of them benefitted from Trumpet Flower’s shade. It is painted silver to recall the proverbial tinfoil hat worn by paranoiacs: it is a symbol of maintaining sanity.

Bounty, a work sharing its title with the show, is a room-sized installation. The front of Bounty is corrugated metal, weathered and rusted (presumably salvaged), with a curved metal lattice of the kind that form the framework of Renner’s large public sculptures. Hanging from that are the letters that form the word “BOUNTY.” They are white, three-dimensional, and in an old-fashioned display type that calls to mind 19th-century circus posters. This is a remnant from a Thanksgiving float, H-Town Bounty, that Renner made with Alex Larsen in 2013. It took the form of a cornucopia — echoing the shape of Funnel Tunnel and Trumpet Flower — on a trailer. Inside the cornucopia was a tiny half-pipe on which skateboarders did tricks.

Around the corner, this wall is attached to a pale blue wall, which leads into another wall — this one constructed of large shelves on which are piles of varied scraps of lumber and other objects. An opening in this junk-storage wall leads to another space. The opening is a person-sized curvilinear hole constructed of multicolored parallel slats of wood — it would remind one a bit of Moorish architecture if it weren’t asymmetrical.

When the viewer goes through this curved portal, she finds herself in a new gallery, which is much less cluttered than the junkyard on the other side. To the right in this space are two sturdy, well-worn work-tables — one sitting horizontally, the other tilted onto its edge. One has an enormous rusty vice attached to it that holds a folding ruler in its jaws. This is titled four generations. This table was Renner’s father’s workbench. The well-worn workbench beside it belonged to his grandfather. High up on a wall opposite is best collabst, a circular object made of strips of wood (Renner’s favorite material) formed into a disc adorned with multi-color scribbles. This is a collaboration between Renner and his very young son, Indiana Renner Peacock. Like Courbet did in The Painter’s Studio, Renner looks at his past and anticipates his future. (Memory and time have long been concerns for Renner, as seen in his installation chamber #4 (bounded operator) (2012), which looks at both personal and geologic archeology.)

In literary criticism, there is a term, “poioumenon,” which refers to a literary work whose subject is the creation of a story, including, possibly, the story that the reader is reading. Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov is an example of a poioumenon. I’ve never heard it used in reference to a work of visual art, but Box with the Sound of Its Own Making by Robert Morris (1961) might be considered a poioumenon. Bounty might as well — Renner includes in it two work-benches, and All Paint Sales are Final, a piece made of paint lids from cans of paint that Renner used to make his sculptures. In Bounty, we see the story of the creation of a Patrick Renner sculpture — the piles of wood and other materials from which it might be made, the objects he uses to make it, the remnants of art supplies, and the finished work (the Trumpet Flower model and the Funnel Tunnel remnant).

In Isla de la Plata, the quality of being a poioumenon is animated. Isla de la Plata is a mechanical device that mimes a bamboo pole dipping a paint-brush into a can of paint on the floor. This recalls Tinguely’s series of machines called “meta-matics” which produced actual paintings on rolls of paper. Isla de la Plata doesn’t do any actual painting, but in its crude mechanical operation, Renner’s device resembles Tinguely’s inelegant mechanical devices. Isla de la Plata began life as Our Binocular Vision, an installation for the Blaffer Art Museum’s series Windows into Houston, which was a program of window-based exhibits held downtown while the Blaffer was being rebuilt. It was built by {Exurb}, a collective that included Renner as a member (the other members were Johnny Di Blasi, Eric Todd, and Stephen Kraig; they brought in additional members for specific projects). All the works by {Exurb} I’ve seen involved some kind of technology — sometimes fairly sophisticated, as in a work titled Input/Output, but sometimes relatively crude, as in Binocular Vision. The mechanism in Binocular Vision could have been something salvaged by Jean Tinguely from that New Jersey junkyard in 1960.

In addition to the installation at Redbud, there are discrete works of art by Renner. They’re made from detritus that he scavenged, and they are all quite beautiful. Green Thumb (2019) is mostly green and somewhat thumb-shaped. It’s three-dimensional, but hung on the wall, and it incorporates live plants. And, like the rest of Bounty, it is a trip through Renner’s autobiography; among the reclaimed material used to make it are “leftover wallpaper from my childhood home.” The plants are a “random assortment of cacti and succulents (left over centerpiece from my best friend’s wedding reception).”

Scum angel (2019) is flat against the wall, formed of boxy shapes and rounded corners. It is bounded by bent metal. It has an irregular shape that reminds me of a left-facing cartoon duck. Within the metal outline is a variety of detritus, some more junk, some reused art, and family artifacts — a piece from H-Town Bounty, from Funnel Tunnel, from his grandfather’s house, from uncle Keith’s collection of odds and ends, etc. As a composition, this one piece is kind of a recap of the installation as a whole.

Yeahyeahyeah and suresuresure (both 2015, made in collaboration with Alex Larsen) could almost be paintings. They’re each modest-sized, just right hanging in your living room. But like virtually everything else in this show, their materials are varied bits of junk, reclaimed and repurposed. Renner may employ paint and create painting-like objects like scum angel, yeahyeahyeah and suresuresure, but he’s not a painter.

One piece that expresses this fact directly is a wall-collage called PIDLLP, which is short for “Painting is dead, long live painting!” It’s made up of various found objects, as well bits of work-in-progress fragments (for example, cardboard with spray-paint tests), his grandmother’s palette, and a novelty sign with the letters “LHOOQ” above it. This was the title of Duchamp’s infamous readymade of a postcard of the Mona Lisa with a mustache drawn on it. “LHOOQ” is a pun on “Elle a chaud au cul,” French for “She has a hot ass.” In this assemblage, Renner acknowledges two historical precursors — his own grandmother, and Duchamp.

I can’t think of an artist more obsessed with memory, history and time than Renner is. In the {exurb} installation Mnemonic Cinema (2011), in chamber #4 (bounded operator) from 2012, in the Core Samples he made in the same year, and now in Bounty and its various constituent parts (scum angel, four generations, etc.), Renner acts simultaneously like a geologist, an archeologist, a historian, and a nostalgist, in the service of producing a massive autobiography.

On view at Redbud Gallery, Houston, through March 26