The following email conversation took place over the last few weeks.

Neil Fauerso: After Trump was elected, someone on Twitter glibly wrote: “Well at least we’ll get some good art and music.” The implication being that times of political strife, oppression and authoritarianism produce more vital and interesting art. There is a great quote from the classic film The Third Man (written by Graham Greene) that sums up this line of thinking. Orson Welles’ charismatic villain says: “You know what the fellow said — in Italy, for 30 years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had 500 years of democracy and peace — and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”

There are several questions I’m interested in here. Do bad times produce better art? Has the art in the Trump era been a righteous response to this monstrosity of his administration? What is the “best” artistic response to an appalling political and cultural situation? Despite my desire to believe that art can have a furious power and actually stand up to outrages, I find this quote by Kurt Vonnegut pretty compelling: “During the Vietnam War, every respectable artist in this country was against the war. It was like a laser beam. We were all aimed in the same direction. The power of this weapon turns out to be that of a custard pie dropped from a stepladder six feet high.”

I know this is a very broad topic, but what do you think?

Christina Rees: Certainly we see outrage. That makes in into some of the art we’re seeing. I’m with Vonnegut on how that may not be the kind of cultural protest that leads to policy change, but, there’s a lot of really powerful work out there right now, whether we think of it as “post-Trump” or not.

(I’d like to make clear that artist-led activist protests — like Nan Goldin going after the Sacklers, or Hannah Black making written cases for boycotts — do seem to get traction with art institutions and artist who show in them. This is not the same thing as actual artwork changing the policies of a government administration, or even the opinions of a politician’s voter base.)

On the social media I was following post-election, the kind of art so many people seemed to be referring to or hoping for in regards to being a reaction to Trump or the rise of his brand of conservatism (or Bannon’s, or McConnell’s) was the idea of something punk. As in, anti-establishment creativity that just blows the top off of any set of expectations of what art is even meant to be or look like. Like the new cinema in the late ’60s, when the Hollywood system started to be crushed by independent filmmakers. Or thinking about how UK Prime Ministers Heath through Thatcher gave us British punk in the ’70s and early ’80s, and recession and Gerald Ford in the White House and Mayor Beame in NYC gave us the downtown scene in New York in the mid-’70s.

Back then, the whole point (especially in the New York and cinema example) was that young creative people were completely uninterested in what the “adults in the room” were up to, which was generally status quo mixed with more conservatism, corporatism, commercialism. Money. During those diminished eras, the kids made art for themselves and their friends, really (music, movies, art, fashion) and if the shock value resonated against the establishment, so be it. The grownups maybe wrung their hands over it, or attempted to censor it, if they even knew it was happening. (John Waters comes to mind.)

There are cultural waves going on right now that you and I don’t even know about. I think. Will it resonate long-term? Will it influence art for years to come? Will, for instance, Soundcloud DIY hip-hop nihilism ever reach anyone other than the kids making it or the kids it’s made for? I think it will. The razor’s edge of culture tends to slide upward, though in increasingly softened and commercialized reprises of an original impulse.

It’s pretty easy to put one over on Trump and his base. The most creative people out there with the most to say certainly have no interest in making work that speaks to them. What would be the point?

NF: I think we have an aesthetic picture of “art in opposition” that is sort of frozen in the amber of 1970s and ’80s punk. This is akin to the way the aesthetics of “psychedelia” seem frozen in 1960s imagery. But I think a better way to think about this is the mission of the reaction rather than the aesthetics of a particular time. In times of outrage, upheaval, injustice, trauma, etc., art can react in four primary ways: to bear witness, to howl in response, to provide a transcendent break or escape, or to fight back in materialist terms.

I think the last one is the rarest and most difficult to “pull off” given its proximity to propaganda, and therefore the works are calibrated towards maximum impact without subtlety or nuance. Consider two books published within a year of each other in 1851 and 1852, respectively, Moby-Dick and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Moby-Dick received mixed reviews upon publication and is now regarded as perhaps the greatest American novel; Uncle Tom’s Cabin actually significantly shifted public opinion towards abolition, and is virtually unreadable today because of its sentimentality and extremely dated racial depictions. I think this type of art is necessarily of its time and not really meant to age.

Various ages and outrages will naturally attune to and inspire one of the four modes described above. After WWII and the Holocaust and the dropping of atomic bombs brought civilization to the literal brink of annihilation, understandably, the art bore witness, using minimalism and monochromatic palettes (such as Rothko and Yves Klein) to provide a window into the abyss, while music such as Olivier Messiasen’s Quartet for the End of Time, or Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima seemed to approximate a choir of the dead. The ’60s — with the American empire roiling with crazed state violence (Vietnam, Kent State, state resistance against civil rights) unsurprisingly inspired the desire to escape — hence the proliferation of road-trip movies (Easy Rider, Two-Lane Blacktop, etc.). The ’70s and ’80s, with their sclerotic conservative governments grimmining (thats a grimace grin that Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan both excelled at) in pancake makeup while slashing safety nets, inspired a nihilistic roar of insouciance.

So what are we getting now? You’re right, we’re probably not even aware of a lot of it. I can certainly understand where nihilistic Soundcloud rap comes from, given looming environmental apocalypse and an existence of grinding instability for most, but I don’t particularly like it. As I’m thinking about this now, I think that given how grotesque Trump and his administration is and how they essentially defy serious critique (as Trump would say: “Very BORING and low rated”), I find myself drawn towards art that provides a break or an escape. This doesn’t necessarily mean that these works will turn a blind eye toward our current realities. My two recent favorite films both profoundly consider the ides of identity, immigration, and refugees. Ciro Guerra’s Birds of Passage depicts an epic crime tragedy of Wayuu Indians in Colombia spanning generations and introducing the viewer into an incredibly rich culture our current government would simply slander at their most polite as “others.” While Christian Petzold’s Transit adapts a novel from 1942 by Anna Seghers, a German Jewish writer who fled the Nazis in 1940. Transit the novel is semi-autobiographical and the film brilliantly updates it to present day. The (white) refugees sit in purgatorial anxiety in Marseilles, fearful of a looming fascist force closing in. Petzold subtly universalizes the plight and psychic waking nightmare of being a refugee. Both films are entrancing and transporting but fully vital and relevant to these times.

What do you think? What works have stood out to you in the last couple years?

CR: I think one of the reasons we (I mean generationally, culturally) keep looking back to earlier eras — hindsight — of what great art looked like in troubled times is exactly that: hindsight. We recognize it because we’re taught to, and can learn to on our own how to recognize it, too, if we’re looking at enough of it (this is one way curators keep coming up with shows from artists who were once overlooked). That and the the fact that all that art took place in an analog era where we understood the mechanisms of distribution and audience. Your examples of great art in bad times are also mostly from the past, with the exception of a couple of recent movies. We aren’t the only two people or critics who cite on-screen narratives as one of the most recognizable current platforms of innovation and free speech, action and response to current times. I call attention to this because the shows or movies can be radical while reaching an audience that the chattering classes can actually trace.

I think one thing that a lot of artists are facing is the ultra-corporatization of creativity. Also, cancel culture, when one loud person or small group decides they’re offended by something and burn the whole thing down, sometimes even before that creation goes really public. I suppose I’m doubling down on the possibility that big things are brewing in the newest generation of creative people, and we just don’t know what it looks like… yet. I think technology will have a lot to do with how it moves, evolves, and reaches its intended audience, even if it’s a negative reaction to technology, and certainly if it’s a very negative reaction to the world they’ve inherited. I so want to believe this.

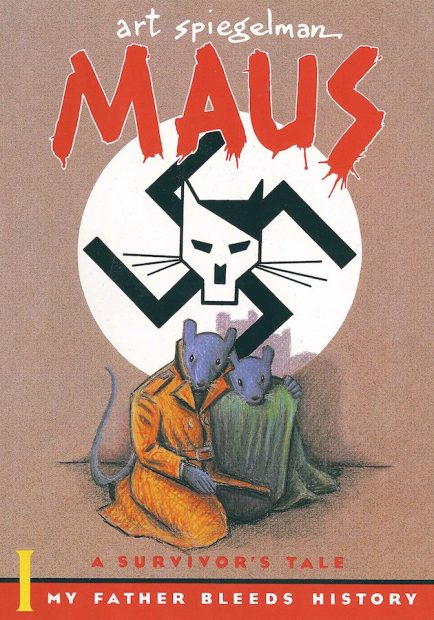

There’s a current news headline about Art Spiegelman, the great writer and Pulitzer-winning comic creator of Maus, pulling an essay he wrote for Marvel for a collection they’re releasing. Marvel didn’t like that Speigelman refers to Trump unfavorably and wanted to delete that section of his essay. He refers to the original superhero creators as being mostly Jewish immigrants in NYC, post world wars, reacting to anti-semitism and the Holocaust. He’s implying fascism connections between then and now, and Marvel wanted to quash it.

There are a lot of people who I wish were still alive, who had sweeping, clear views of humanity and its path, and I would have liked to hear what they have to say about what’s going down now: Are things as bad as we think they are? Philip Roth comes to mind. Baldwin, Orwell. But I’d be happy to hear from Art Spiegelman, too, who is alive and has something to say, and he’s being effectively censored. By MARVEL. Which would not exist without the Jewish immigrants in NYC who created the all heroes and villains for them. Though, with our news cycles, no one will remember this in two days. And most 19-year-olds don’t know who Spiegelman is, anyway.

This is where I wonder if the generation gaps will always be an issue when it comes to people making art that gets traction. Also, where I wonder if the way Gen X (my generation) has raised their kids is erasing the impulse of young people to act out — like really act out (i.e be punk): moving into shithole apartments in large cities with a critical mass of other creative young people, and making things happen, usually with a big dose of drugs, sex, booze, poverty, and total freedom from oversight. Doing things that separate their identities from their parents’. How does ‘acting out’ land if it’s just bad incel conversations on 8chan that ultimately lead to shootings? It ain’t art, that’s for sure.

I realize I haven’t answered your questions. I see a lot of strong art these days that deals with current issues, but the smart stuff is subtle and very complicated. Postcommodity is an art collective I mention a lot as an example of complex and meaningful art for this era. But I’m with you, too, on looking for beauty and some escape.

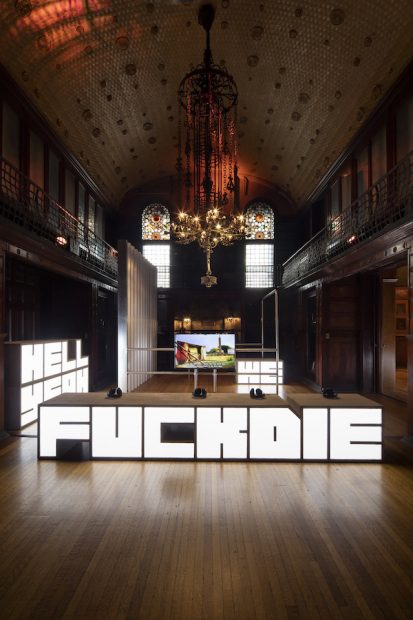

Hito Steyerl, Hell Yeah We Fuck Die, 2016, 4 minutes, HD video, environment. Installation view at Park Avenue Armory, New York, 2019.

©JAMES EWING

NF: I think you’re right that we won’t know which art really responded to this era until we look back in hindsight. These things have a long tail, after all. But I also wonder if the unique grotesquerie of these times, combined with a panopticon of technological surveillance through social media, et. al., and a paralysis brought on by relentless knowing (e.g. news all the time, constantly, some of it fake or dubious) — in conjunction with little agency and high desperation — poses structural challenges for response, be it art, or actual praxis.

I find myself often feeling in a sort of amorphous globalized way, “We are not really up to this are we?” By this I mean global environmental catastrophe and the consequential rise in authoritarian ethno-nationalism. Think of the furious rise of white supremacy and nativism in Europe and the United States in response to one million refugees and migrants entering in a year. What’s the reaction going to be like when it’s ten or twenty times that? I believe that there really are only two options: a global cooperative effort that would necessitate a level of government intervention and state planning that many would describe as “socialism,” or walled ethnostates that horde resources and shoot anyone who tries to climb over. I think Donald Trump and many of his supporters want the latter, even if they don’t quite say it so directly; it’s really on the tip of their tongues, isn’t it? And I think they are most definitely up to it.

Take the Greenland thing. It’s of course patently absurd, Onion-headline, Scanners head-exploding madness, but as with most Trump things, theres a dark river of the real beneath. Greenland, as the climate warms and the glaciers melt, will be a pretty desirable place to live, with desirable resources. It’s easy to imagine Stephen Miller showing a scowling Trump a powerpoint of Greenland with the caption: “New America — a place for the ‘Right Ones.'”

Conversely, I don’t really think the Democrats are up to it (Pelosi still mentions coming to a bipartisan agreement with Trump, which is like opening a restaurant with Max Cady from Cape Fear). I don’t think a corporatized entertainment industry that breaks its arm patting itself on the back for opening the world of mediocre, CGI-leaden tentpole films to non-white actors and directors is up for it. And I don’t think most people (myself included) are up for it when they’re in a never-ending spiral of trying to make rent, buy insulin, and pay off loans. I think I may unfairly project this feeling of helplessness and despair on the art I see with the implicit yearning to be rendered up for it by the work, or otherwise to escape — to feel a break, a pause, an out.

I wish a lot of people were still alive and magically in fighting shape: Hitchens, Hunter S. Thompson, Basquiat, Sarah Kane, Rainer Fassbinder — artists and writers that had the spine and fury to stare back. The fact that a lot of these people died by suicide (or its chaotic cousin, overdose) speaks to the perils of, as George Orwell wrote, “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.”

CR: What I think is increasingly true is the existence of more than one art world. Because art’s impact is often so ineffable and there’s so much of it, you can choose to engage with the art world that means something to you. (Although that doesn’t let an art lover off the hook from striving to look at a lot of it to get better at one’s relationship with it.) The messy and bracing intersection of art and commerce has been true for centuries now, but at different points in my adulthood, I’ve been led to believe that there is Only One Art World ™ — the world of big galleries and auction houses and collectors vying for totally shit bait like Alex Israel. I’m looking away from that world to find out what’s actually going on out there.

There are of course many art worlds, and while the art worlds we experience in Texas are myriad, and can intersect with the Only One ™ at times, we have the option — everyone has the option — of paying attention to what seems to actually matter. I feel like Glasstire, editorially, has acknowledged some of the problems inherent in explicitly political art, and some problems with activism masquerading as art (and generally doing art no favors).

But overall, I feel like Texas-based artists are every bit as responsive and insightful as artists anywhere, and depending on what they’re paying attention to themselves, their art certainly reflects our times. One of the greatest and most radical things to happen to the art world in recent years is the rethinking of hierarchy and identity. This is in direct response to the simmering white nationalism that reared up as Obama was leaving the White House, and generally the nativism that’s coming up throughout the world.

I mean, there’s no doubt that in spaces that artists create or have access to, we’re seeing far, far more work by artists of color, women artists, and queer artists. We just are. It’s a bounty. It may be the most obvious response (counter-response) to the Trump era we have, and if that’s what we can see so far, I’m happy with that development. I’m not saying the artists whose work we’re seeing would never have been seen otherwise, but I’m talking about the mechanisms for getting the work in front of people— it’s being recalibrated for the better. (There’s always a risk of “overcorrection,” which to me is really just sloppy curatorial/institutional decisions. And slop is slop no matter who puts it out there.)

Juan de Dios Mora, Leading the Camino (Leading the Road), Linocut, 2011, Print/Image size: 18-¼ in. x 23 in., Paper size: 22 in. x 30 in.

There’s a lot of heat in this era’s artwork, and joy, and humanity. And humor.

Sometimes I feel like my tag line for the last couple of years could be: “Just give me Jimmy James Canales’ padded sensory deprivation pod and leave me alone.” But really, I love so many Texas artist’s work that naming names feels arbitrary. All the art out there is why I still get up in the morning.

This is going to sound dramatic, but it’s just true: last night I dreamt a whole city — I don’t know where but I was on the edge of it — was getting swept into a kind of giant, fiery cesspool, and I started crying. Sobbing in the dream. This is so cliché! But I cried because I knew that the loss of this civilization was also the loss of all the signs of humanity that had been created there. The art. It was a ridiculously flat-footed dream in terms of allegory. (I’m no artist.) Though maybe it was no allegory.

But I suppose I just feel that the more art that surfaces now, the better.

NF: I think you’re right that it is crucial to recognize that we are in an atomized age; there is no monoculture, and as you say, there are many “Art Worlds.” I just saw the 40th anniversary 4k restoration of Apocalypse Now (which I highly recommend to everyone) and I think that collectively we still have some expectation for grand sweeping statements that respond to or at least articulate outrage and madness (Apocalypse Now remains the best piece of art illustrating the two mirrored faces of the militarized American empire: genocidal mania cloaked in hero-quest philosophizing; and stupid, flailing, expensive cruelty) — but they don’t really make movies like Apocalypse Now anymore. They make live-action remakes of cartoons.

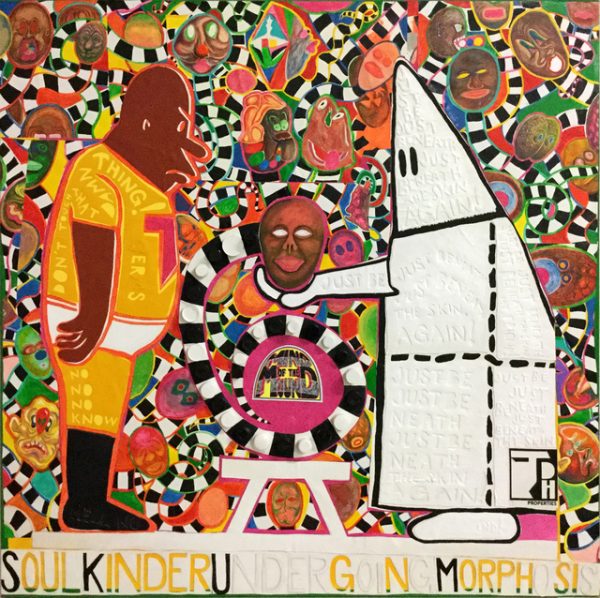

But what we have is not inferior — in fact it is probably more nuanced and egalitarian than (white male) “auteurs” in the field making epics. The bounty of different voices in all forms of art, if one makes an effort to seek them out, undoubtedly makes the world more bearable, and makes one more empathetic and certainly feel less alone. And there are many, many artists in/from Texas directly engaging in these brutal and horrifying times through one or some combination of the models of response I wrote about earlier: Trenton Doyle Hancock, Jimmy James Canales, Michael Menchaca, Jose Villalobos, Christie Blizard — most of the artists we talked about in our Top Five video about the ‘most twisted’ artists in Texas.

One of the things I like about living in Texas: is it is a (large) microcosm of the world in the way that Idaho, or Delaware, or Lichtenstein is not. All of the pressing issues are here, front and center: migration, borders and walls, climate change and drought. Texas artists responding to Texas and using imagery and symbols of the region are responding to the world. It’s a cliché to say this but in Texas, I truly feel the local is global.

I think your dream reflects the deep-seated despair and dread permeating us on an emotional and unconscious level. The Amazon is on fire; it can be seen from space. The Amazon provides 20% of the world’s oxygen and is a huge sink of carbon. It is the lungs of the world. It is on fire because the proto-fascist president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, gave the green-light to agribusiness to clear-cut and burn for livestock grazing. If the fires keep burning, they will cross a point of no return and the Amazon will become a permanently dry savannah. The ambient horror (to quote the end of Apocalypse Now: “The horror…. the horror!”) is fairly difficult to process. It expresses itself in the feeling of helplessness I described above and perhaps your dreams of loss. I think it is fair to say that to live without art in these times would probably be unbearable.

CR: Here’s the really depressing thing in the current sociopolitical reality: this conversation between you and me is taking on a sweeping subject, but it’s still presented in a bubble. The hard reality is that many people wouldn’t know an artwork is both transgressive and beautiful — that it’s sublime — because they don’t have a fundamental grasp of those concepts when it comes to art. And if Aunt Sheila in Missouri doesn’t think anything is art that I think is art — whether it’s work by Kara Walker or Trevor Paglen — then just putting new ideas or perceptions out there in any creative form is in itself pretty punk-ass, and will not reach Sheila’s soul in Missouri. The only people “reading” it are… it’s preaching to the choir. In a sense. By that I mean that there is no way Kara Walker’s art, no matter how powerful and precise it is, is going make a dent in how some members of my extended family will vote in the upcoming election.

If a huge swath of people who claim to “like art a lot” know who KAWS is but have never heard of Walker (or Warhol), art is in some big fucking trouble. (It really is Idiocracy turned real.) And who fell down on the job with that one? Curators? The media? Education boards? It wasn’t the artists, that’s for sure. They’re just out there making the work.

Of course, as I mentioned earlier in this convo, how can I assume to know exactly who Kara Walker (or any artist) makes art for? (The answer is generally, understandably: The biggest audience my work can speak to.) If her work is in fact inspirational to generations of creative people (and voters), then how is art, in this respect, a bubble problem?This is just another in a long line of dire weeks in the news. I think that dream I had followed all the headlines on Trump’s trade war with China and the fires burning the Amazon. I was reading some of David Koch’s obits, and my prevailing thought was (and not the first time): “Extremely rich people seem to want to live in a world where truth and beauty cannot possibly spontaneously happen.” They want to control everything, including art and nature, and that completely extinguishes any chance for art and nature and to thrive. Who wants to live in that world? What are artists meant to do with that information? To lot of people who call the shots out there, artists are seen as two totally conflicting things at once: 1) they have the natural power to make amazing things that give humankind a reason to get up in the morning, so they are indispensable, and, 2) they are pains in the ass, and need to be controlled and censored.

What kind of Sisyphean turmoil are artists getting set up for, here? It’s hard to want to make things when anything you make could be considered “oppositional” just by existing. And of course if the overriding message for creative people is that, if they want to make a living making things, they must make things that look good for social media, which is just an establishment game, then… ?

You and I may know what the most affecting post-Trump art is, because we’re looking for it. All the time. We’re looking right at it, here in Texas and beyond, and being affected by it. There’s a lot of it, too. The fact that artists are still getting after it has sometimes got to be enough. We are all doing the best we can.

NF: Well, yes. What we’re talking about here is preaching to the choir. The idea of a modern Silent Spring, the idea of a work that would cause widespread awareness and horror of the “DDT” of ethno-nationalism and white supremacy is literally unimaginable (look at the conservative reaction to the profound, deeply erudite and well-researched 1619 Project, which has been a confluence of pearl clutching, dismissiveness, and rage). But the choir does need to be preached to.

One of the huge bummers to me is that the internet offers the ability to: basically get a master’s-level education for free in any subject (through open universities), watch many of the great films, listen to what was on the radio in Senegal in 1963 — true wonders of the world. Instead, for the most part, we use the internet to consume mediocre entertainment, give our personal information to social media, and get swept up in the churning rapids of rumors and fake news. I honestly don’t think we were ready for it.

This is a fairly bleak conversation, but these are bleak times. And they are made bleaker by (I realize this may sound snobbish, but there’s no other way to put it) waves of mediocrity that seek to attract most of our attention: faddish, Mr. Brainwash (from Exit Through the Gift Shop)-style art like KAWS, ham-fisted and broad prestige TV lauded as genius, garbage tentpole films for American Cinema, and a vampiric flesh stripping of actual journalism by rapacious private equity (local news is quickly becoming just a propaganda arm of bronzed, chiclet-toothed Trump Davidians). It may be easier technologically to be an artist now (in terms of taking pictures, making films, posting art, recording music, etc.) but it’s certainly less fun, and seems generally worse. There is the crippling expense of living in cities; the risk of making anything too aggressive, oppositional, transgressive, difficult, dangerous; and the general condescension that one’s art (especially if it’s difficult) is a frivolous, egomaniacal, wanky endeavor. So yes, you do have to look for it.

Bruce Conner, a San Francisco-based artist, died in 2008. This is a still from Conner’s CROSSROADS, 1976. Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

And I am enormously grateful to artists who do make work in a variety of approaches and tones that is real, vital — an oasis, a cleansing flame, a clear moon for this nightmare desert. I was recently in San Francisco for a friend’s wedding. I remember going there in the ’90s when my sister lived there and being completely blown away and beguiled by the city; it was relatively cheap then, truly multicultural, transgressive, bohemian. Now it has an eerie quality, like the way cities are depicted in zombie films after a cataclysm. It feels cold and strangely empty; there are few children and so many homeless people living in despair. I went with my friends to a sound installation space called Audium — a decades-long project by an electro-acoustic composer (and now his son following in these footsteps). The space has 176 speakers and the concerts are in complete darkness. Like much electro-acoustic music that’s experienced in serious concert settings, the effect is similar to a sonic spa. I felt refreshed and clear-eyed, and the experience of being totally quiet and “in key” with strangers felt genuinely sacred for a non-believer like me.

I think this is what we cling to, whether it’s meditative sound pieces, or polemical performance art — something outside the carousel of inanity. To me, making such work and responding as the audience is the opposite of frivolity. It’s actual self-care, in the sense that I honestly do not know how I would live without it.

![Kara Walker, The Katastwof Karavan, 2018. [Photo: Alex Marks]](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/kara-walker-2018-600x400.jpg?x88956)

2 comments

Thank you. Worth a re-read. Shared.

Regarding Art in the age of Trump. Although I agree that anger or hate towards Trump and his administration may bring creative and powerful art, and most artist feel this way because artist have a “F the system” standpoint mostly, but I feel you are missing a large group of artist. I myself am a supporter of Trump and his policies. As an artist, I have many feelings of oppression due to the discrimination, persecution, and attempts to embarrass or shut up my beliefs for support for Trump. It is not right to assume that everyone dislikes and has negative views about him. The fact that your piece only mentions artist as if we are all against him leaves many of his artist supporters unspoken for. I went to an artist workshops for example, and was very exited to learn, but when the instructors make little comments about the administration and other artist who know my political stance try to single me out, as if there is something wrong because I do not hate Trump, that is oppression. I feel it is OK for us as artist to express and use our art to bring awareness to things we feel unjust and not right. But when you try and isolate, humiliate, and do not even include the point of view from the other side, it is wrong. Basically not all artist hate Trump or feel his policies are wrong. And we are also tired of being forced to shut up and go with the flow because of not wanting to deal with the bias. And sometimes we just want art not to listen to peoples hate. But I do admit this has also inspired me to have ideas for pro trump, I’m just weary of my work being damaged, and I feel that is one way I am being oppressed by other anti-trump artist, which is wrong and should not be encouraged. We should respect art and others views even if they disagree with yours. Thank you for your time.